Course lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Session 7

This spring, Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal and the first Facebook investor, held a course in Stanford - “Startup”. Before starting, Thiel stated: "If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject you will have to study."

One of the students of the lecture recorded and laid out a transcript . In this habratopic, SemenOk2 translates the seventh lesson. Formatting 9e9names . Astropilot Editor

Session 1: Future Challenge

Activity 2: Again, like in 1999?

Session 3: Value Systems

Session 4: The Last Step Advantage

Session 5: Mafia Mechanics

Activity 6: Thiel's Law

Lesson 7: Follow the Money

Session 8: Idea Presentation (Pitch)

Lesson 9: Everything is ready, but will they come?

Lesson 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Lesson 13: You are not a lottery ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder — Sacrifice or God

Session 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

Lesson 7. Follow the money.

I. You and Venture Capital

Many people creating a new venture have never come across venture capitalists. Founders who actually interact with venture capitalists do not need to do this at the initial stage. First, you team up with the founders and get down to work. Then, perhaps, you attract friends, relatives or “business angels” to invest. If you still need to increase the amount of capital, then you need to know the principle of venture capital. It is very important to understand how the venture capitalist thinks about money, or, in some cases, how he does not think about it and, accordingly, loses it.

')

Venture capitalists appeared in the late 40s. Prior to this, wealthy individuals and families often invested in new enterprises. But the idea of combining funds that would be invested by professionals in companies at the initial stage of development was born in the 40s. Send Hill Road, the forerunner of Silicon Valley, appeared in the late 60s, along with the leaders of this area - the Sequoia (Kleiner Perkins) and Mayfield fund (Kleiner Perkins) funds.

In general terms, a venture capital firm works as follows. You collect a lot of money from people called limited partners. Then you take money from this fund and invest in portfolios of companies that you consider promising. If all goes well, over time these companies will become more expensive, and everyone will make a profit. Therefore, venture capitalists play a dual role, prompting limited partners to give them money, and then find successful (in the long run) companies for their return.

Most of the profits are returned to limited partners as investment income. Venture capitalists, of course, have their share. A typical model, called 2-and-20, means that a venture capital firm charges an annual management fee for funds - 2% of the fund and receives 20% of the profits, excluding initial investment. Theoretically, a 2% commission for managing funds is already enough to continue the work of a venture capital firm. In practice, the amount may be much larger. Under the 2-and-20 model, a fund of $ 200 million will earn $ 4 million in management fees. But, of course, we must admit that the real income expected by venture capitalists comes from a 20% share of the profit, which is called “deferred” (“transferred”).

Venture capital funds have been operating for several years, since it usually takes years for companies in which you have invested money to grow in value. Most investments in such funds either do not make money or fall to zero. But the idea is that a successful company will more than return all your investments. As a result, your fund will become more than the original investment of partners with limited liability.

There are many criteria for a successful venture capitalist. You must be able to reasonably evaluate companies, identify outstanding entrepreneurs, etc. But there is one particularly important factor that few understand. Undoubtedly, the fundamental principle of a venture capitalist is to use the power of exponential growth in their own interests. This is just the initial mathematics, which may seem strange. Just as arithmetic at the 3rd grade level — knowing not only the number of shares received, but also dividing them into outstanding shares — is crucial for understanding share capital, 7th grade mathematics — exponent knowledge (exponent) - is essential for understanding venture capital.

Einstein's famous quote - compound interest - is the most powerful force in the universe. Viral growth of companies can be seen as confirmation of this idea. Successful enterprises tend to exhibit an exponential arc. It is possible that they increase in size by 50% per year, which has been summed up over several years. Growth can be more or less sharp. But this model - a significant period of exponential growth - is the foundation of any successful technology company. And during this exponential period, valuations of companies tend to increase exponentially.

So, consider a hypothetical successful foundation. Over time, the fund invests all available funds and the growth of the investment portfolio stops. This happens pretty quickly. Successful investments grow exponentially. Sum up all investments during the life cycle, and get the curve in the shape of the letter J. At the beginning there is no profit. In addition, you need to pay a fee manager. But then exponential growth happens, at least in theory. As you start below zero, the main question is when will you be able to “emerge”. Many funds do not succeed.

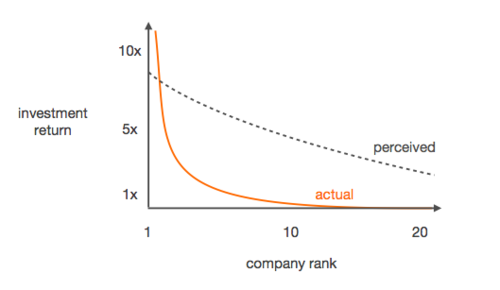

To answer this main question, you need to ask one more: what is the distribution of returns on invested capital in a venture capital fund? The naive answer would be this: simply arrange the companies in diminishing on the basis of their income in relation to the amount of investment. People tend to divide investments into three groups. Bad companies don't make a profit at all. Mediocre firms may make a profit in the amount of investment, so you will not lose much, but you will not earn much either. Finally, great companies make an average of 3-10-card profits.

But this model lacks a key point: the actual profit is extremely asymmetric. The more the venture capitalist understands this asymmetric scheme, the more successful he is. Unsuccessful venture capitalists usually believe that the dotted line is flat, i.e. that all companies are created on an equal footing, and some simply fail, others are treading water or growing. And in fact, you get a distribution based on an exponential law.

(investment return - the return on invested capital, perceived - perceived, actual - real, company rank - category of companies)

An example will help to clarify. If you consider the foundation of the company Founders Fund sample of 2005, it turns out that the best investment is more effective than all the others combined. And investments in the second best company in the list were about as valuable as in all the others, starting with the third and to the end of the list. The same dynamic was maintained throughout the fund. This is the distribution based on the exponential law in practice. As a first approximation, a venture capital portfolio will only bring in money if it turns out that your best investment in a company will be worth more than your entire fund. In practice, it is quite difficult to be as profitable as this venture capital fund, if you do not fall short of these numbers.

PayPal was sold to eBay for $ 1.5 billion. Investors who funded PayPal at the initial stage had a fairly large share, and as a result, their investment was worth almost as much as their entire fund. The rest of the fund's portfolio was not so profitable, so to some extent they reached the break-even level with PayPal. But investors of PayPal Series B did not cover the costs of their fund, despite the fact that they successfully coped with the investment in PayPal. Like many other venture capital funds in the early 2000s, their fund lost cash.

The fact that the return on invested capital is based on the principle of distribution according to the exponential law allows us to draw the following conclusions. First: you need to remember that in addition to the management fees for the funds, you receive money only in case of return of all invested funds with an increase. At the very least, you must reach 100% of the capital. So, taking into account the distribution according to the exponential law, you should ask: "Is there such a rational scenario, in which our share in this company will cost more than the entire capital?".

The second conclusion: taking into account the distribution of the exponential law, you should be quite concentrated. If you invest in 100 companies to try to hedge by volume, then you are doing something wrong. There are few business areas in which you can get the required high degree of confidence. The best investment model is 7 or 8 promising companies, from which, in your opinion, you can get a 10-fold profit. In theory, mathematics offers the same thing if you try to invest in 100 different companies that you think will bring 100-fold profit. But in practice, it looks more like the purchase of lottery tickets rather than an investment.

Despite the fact that the exhibitor is studying in the course of high school mathematics, it is rather difficult to work out this type of thinking. We live in a world in which usually nothing happens exponentially (exponentially). Our usual life experience is fairly linear. We extremely underestimate exponential things. If you do a retrospective study of the Founders Fund portfolio, one heuristic rule that worked just incredibly well is that you should always exercise your right to proportionally increase your share of investment in a portfolio company when a smart investor seeks to grow a company in the current round of investing. Conversely, the study showed that you should not increase your investment in case of frozen or diminishing value of the investment portfolio.

Why are there so many wrong valuations of companies? One of the guesses: people do not believe in the distribution of the exponential law. They intuitively do not believe that the return on investment can be so spasmodic. Therefore, when you have an increase in the price of shares with a large increase in value, many, or even the majority of venture capitalists are inclined to believe that such an increase is too large, and therefore they underestimate the shares. Practical example: Imagine that you are working in a startup. You have an office. You have not yet reached the exponential growth phase. Then comes the exponential growth. But you can ignore this change and underestimate the important shift that took place, simply because you are still in the same office, and much looks the same.

Financing should be avoided if the value of the shares does not increase in this round. This means that, in the opinion of attracted venture capitalists, the situation could not deteriorate so much. Such rounds are initiated by those people who think that they can get, say, 2-fold return on investment. But in reality, often something goes out of the ordinary badly, and as a result of this the price of shares will never rise. This heuristic rule should not be taken purely mechanically or as an immutable investment strategy. But in fact, this rule is fairly well confirmed, so at least it makes you think about distribution based on exponential law.

The concept of exhibitors and exponential distribution are not only important for understanding venture capital. The same principles apply in everyday life. Many things, such as key decisions in your life or a decision to start a business, lead to a similar distribution of results. We tend to think that the range of possible outcomes is small — a little better, a little worse. In reality, the spread is much more significant.

Not always, of course. Sometimes a flatter perceived curve, oddly enough, fairly closely reflects reality. If you, for example, were thinking about working in the postal service, then the perceived curve will probably be correct. You get what you see. And there are a lot of these things. But it is also true that, for one reason or another, we were taught to think mainly in this way. Therefore, we tend to misjudge the situation where the perceived curve, in fact, does not accurately reflect reality. The context of a technology startup is one of those places. In fact, the deviation from a straight line in terms of distribution for a technology startup is indeed significant.

This means that when you focus on the size of your share in the company, you should change your perception. In terms of exponential distribution, the place occupied by your company on the curve is just as important or even means much more than the size of your share.

With other things being equal, it is better to have 1% of the company than 0.5%. But the hundredth employee at Google received much more than the average CEO of a typical venture capital company over the past ten years. Distribution is worth serious consideration. You could use this as an argument against joining a startup. But do not go so far. Exponential distribution simply means that you have to seriously consider where the company will be located on the curve.

The opposite opinion is that the standard perception is reasonable or, at least, not unreasonable, since in fact the distribution curve turns out to be arbitrary. It claims that you are just a lottery ticket. This is not true. Later we will talk about why this is wrong. For now, it suffices to emphasize that the actual curve is an exponential distribution. You do not need to know all the details and the deep meaning of what it means. But it is important to realize this. Even a drop of understanding this parameter is extremely valuable.

Ii. View from Sand Hill Road

Peter Thiel: The thing we need to talk about is what secrets venture capitalists resort to for profit. In fact, most do not make profits. So let's talk about this.

Roylof Bota: The unprofitability of venture capital is well known. Average yield has remained at a fairly low level for several years. According to one of the versions, when in the 90s venture enterprises earned good money, this was an important event for following the blind recommendation of investing more and more money in venture enterprises. Therefore, there may be an excessive amount of money in this industry, and most companies have a hard time making money.

Peter Thiel: Paul, what should entrepreneurs do so that venture capitalists do not take advantage of them?

Paul Graham: In fact, venture capitalists have no predatory intentions. The Y-Combinator Venture Fund is a bench for a minor league game. We are directing people directly to venture capitalists. Venture capitalists are not evil or deception, nothing of that sort. From the point of view of making a good deal, not a bad one, and this applies to any deal, the best way to get a good price is competition. Venture capitalists must compete with each other to invest in your enterprise.

Peter Thiel: We discussed in this lesson how frightening competition can be. But perhaps not too bad when venture capitalists enter the competition. In practice, you never use just one investor. Most likely, you will be interested in either two investors, or none. Here is a cynical explanation for this: most venture capitalists are not confident in their ability to make decisions. They are simply trying to imitate the decisions of others.

Paul Graham: But investors are also interested in waiting. Wait - it means to be able to get more information about this company. Therefore, waiting is bad for you only if the founders raise the price, while you are waiting. Venture capitalists are looking for startups that will be another Google. They are cool about 2x return on investment. But most of all, they do not want to miss such a chance as Google.

Peter Thiel: How not to become a venture capitalist, losing money?

Roylof Bota: Since the distribution of the results of investments in start-ups follows an exponential law, one cannot simply expect that you will receive a profit by simply writing checks. That is, you can not just offer an investment as a commodity. You should be able to help the company in various ways, such as using your connections on their behalf or using useful advice. Sequoia Foundation has been active for over 40 years. You can not get the same profit, just by providing cash.

Paul Graham: Leading venture capital funds are forced to make their own decisions. They cannot follow someone else because everyone follows them! Look at the foundation of Sequoia. This foundation is highly disciplined. This is not a fraternity company business school company that sorts the founders to select guys like Lari and Sergey. Sequoia carefully prepares research documentation for the proposed investment ...

Roylof Bota: But the research is brief. If you are preparing or consider that you need a document of 100 pages, you will not see a forest behind the trees. 3-5 . , .

: , , , . , — . , . , , , , . . .

: LinkedIn — , . , . , . , .

: Y-Combinator ?

: . Right

: . . , , . . , . . , , .

: , «». . , , , 200 . , .

: PayPal 5- . . Those. : 5, , , . . , , . : « 5x, 3 x?».

: , . . 10 , General Motors – , , – . , . , . , .

: , , , , , . PayPal, 300 . 2 . , . . , , .

: , ?

: -, , , . . , , . - . , , , , . — , 2- 3- .

: ? , , , , .

: , , , . . . , 15 . , . 9 - . .

: , , . , , . , , , , .

: ?

: . Founders Fund 7 -10 . — 10- . ? 10 100 , 100 1 1 10 . 100 , . Apple 500 , Microsoft — 250 . .

, , -. - — -, , - (JOBS Act). , , - , , .

: 50%- . . . , . 3-5- . . .

: , 50 , ?

: . , . , , . - . Microsoft Apple. . , .

, . 50 , . , , , !

: , , , 20 18 .

: , , , ?

: . , , . . , . .

: , . , . — , — .

: , , , , .

: . . . , , . , — , , .

: Microsoft. , , ?

: . , , x. , - , x . , . , .

: , . , . , . . , .

: .

: , . « », , . 25% , .

: Sequoia ? ?

: . . ? ? . . , . , .

. , . «» . , . , . , , . , , , .

: 40 2 . , , , . ? ? ?

: . 50- . . -. LISP, CGI . , , 50 — . 1,5 , … [ ].

: : ? , ?

: , , . , «», x, y. , , . Y-Combinator, , Instagram- .

: - , , , . - , , . — , , . Google , AltaVista.

: , , , , . . - . , , , .

: , , ?

: 2 x 2: , , . , .

: , Y-Combinator ?

: . , Y-Combinator .

: , , Y-Combinator. - , -, , . , Y-Combinator, . . . , , - . , .

: ?

: . . . . . . , .

: , .

: .

: , . ? ? ? ?

: , — , . Apple . . .

: « ». : , . , , . , , . .

: « » . ?

: . .

: ? ?

: , - . ? ?

: , , .

: , ?

: .

: PayPal , ? , , — . , , . . , , .

: , . .

: , , . . , . . .

: . , , , . . , , , .

: ?

: . . . . .

: . , - .

: .

: . — . – 2/3 . , , , . .

From the translator:

I ask translation errors and spelling in lichku. I also remind you that this text is a translation, its content is copyright, and the author’s opinion may not coincide with mine.

, SemenOk2 . Formatting 9e9names . Astropilot Editor. All thanks to them.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/159829/

All Articles