Course lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Session 3

This spring, Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal and the first Facebook investor, held a course in Stanford - “Startup”. Before starting, Thiel stated: "If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject you will have to study."

One of the students of the lecture recorded and laid out a transcript . In this case, 9e9names translates the third lesson. Astropilot Editor.

Session 1: Future Challenge

Activity 2: Again, like in 1999?

Session 3: Value Systems

Lesson 4: The Last Turn Advantage

Session 5: Mafia Mechanics

Activity 6: Thiel's Law

Lesson 7: Follow the Money

Session 8: Idea Presentation (Pitch)

Lesson 9: Everything is ready, but will they come?

Lesson 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Lesson 13: You are not a lottery ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder — Sacrifice or God

Session 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

Session 3: Value Systems

In many ways, the story of the 90s is a story of common misconceptions in understanding what value is. The concept of "value" has passed into the psychosocial plane, what people considered as such was declared valuable. To get away from this herd fallacy of the past decade, we must make an effort to find out if it is possible to determine the objective value of a business, and if so, how to do it.

')

If we return to the reasoning from the first lecture, we note that there are a number of questions that may give us ideas about values. These questions are highly personalized. For example: What can I do? Which of these seems to me valuable? What do not do the rest? If we take globalization and technology as the basis, as the two main axes of the 21st century, then all of these questions can be synthesized into one high-level question: what companies, whose value is obvious, have not yet been founded?

A slightly different view of technology - the transition from 0 to 1, if we return to our previous terminology - can be obtained from a financial and economic point of view. This point of view can also shed light on the concept of "value"; let us now consider it in more detail.

I. Great technology companies

Great companies do three things. First, they create value.

Secondly, they constantly stick to the chosen path.

Thirdly, they become monopolists in the production of at least one of those values that they create.

The first of these statements is obvious. Companies that do not create anything of value simply cannot be great. Only the creation of values alone will not make a company great, however, without this, great ones are not exactly becoming.

Great companies are stable. Or, more precisely, they are durable. They do not exist on the principle of "creating value and disappearing soon." Consider companies from the 80s that produce hard drives. They multiplied value by producing new and more advanced devices. But the manufacturing companies themselves did not stand the test of time - other companies came to replace them. It is not necessary to build boundaries between the values that you can produce, and the values that you can seize and hold.

Finally - and this is not by chance - you must capture a large part of the market of the value you are producing, after which your company will become truly great. A scientist or mathematician can create many enduring values with his discoveries. But to capture a significant part of this value market is a completely different matter. Sir Isaac Newton, for example, could not capture most of the values that he created in his work (apparently, it means “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy” - approx. Translator). Take the aviation industry as a less abstract example. Airlines, of course, create value, as life becomes better, thanks to their existence. These companies create many jobs. However, the airlines themselves never really earned money. Of course, among them there are better and worse companies. But, probably, none of them can be considered really great.

Ii. Evaluation

One of the ways that many people try to use for an objective assessment of the value of a company is to find a multiple analogue. To some extent it works. It is necessary, however, to take care to avoid the use of social heuristic estimates instead of rigorous analysis, since the analysis, as a rule, is conditioned by the current agreements and agreements. If you create a company within a business incubator, then you need to take into account existing conventions. If participants invest their funds in the company before reaching the $ 10 million mark, the company can be valued at $ 10 million. There are many formulas that include metrics such as the monthly number of page views or the number of active users. Somewhat more stringent are the factors in calculating income. As a valuation of a software company’s value, it can often be based on its tenfold annual income. Guy Kawasaki offered a fairly unique (and possibly useful) equation:

preliminary estimate = ($ 1 million * number of engineers) - ($ 500 thousand * number of managers)

The largest total multiple is the price-earnings ratio, also known as the P / E ratio or simply the PER. The PER coefficient is calculated as follows:

PER = Market Value (per share) / profit (per share)

In other words, this is the price of the stock relative to the company's net profit. PER is a well-known characteristic, but it does not take into account the growth of the company.

To account for growth, you can use the coefficient PEG - the price / earnings ratio with regard to growth. That is

PEG = (market value / profit) / annual profit growth.

In this way,

PEG = PER / annual revenue growth.

The lower the PEG value for the company, the slower it grows, and, consequently, the lower its value. A higher PEG value, as a rule, characterizes a great company value. In any case, the PEG must be less than one. PEG is a good metric to keep track of your company's growth.

We received a value analysis at a given time. However, in reality this is an analysis of temporal factors. In the course of analysis, you look not only at the cash flow for the current period, but also for future years. Summing up all the values, you make a profit. But the same amount of money today is worth more than in a future period. Thus, the analysis does not take into account the decrease in the cost of money over time (TVM), since the future carries with it a large number of risks. The basic formula for calculating the TVM value is as follows:

r - discount rate

CFt - cash profit in the current year

DPV - present value with discount rate

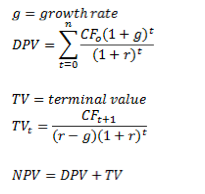

Everything becomes complicated when the value of the cash profit is not a constant value. For variable cash profits, the following formulas are used:

g - growth rate

TV - residual (post-forecast) value

Thus, to determine the value of a company, you are calculating the DPV or NPV coefficients for the next X (or an infinite number) years. In general, you need to get the value of g greater than r. Otherwise, your company does not grow at a sufficient pace to keep up with the discount rate. Of course, in the growth model, the growth rate should eventually decline. Otherwise, the value of the company will eventually reach infinity - and this is unlikely.

The value of firms in the era of the Old Economy is defined differently. For a company in a downturn, the main value is determined by a short-term perspective. Investors who adhere to the value strategy pay attention to the gross margin. If the company can maintain the current level of box office profits for 5-6 years, then this is a good investment. Then investors simply hope that this box office profit — they determine the value of the company — will not decrease faster than they expected.

With technology companies and other fast-growing firms, the situation is different. First, most of them lose money. When the growth rate g, as we designated it in our calculations, is higher than the discount rate r, then the main value of the technology business falls on the distant future. Indeed, in a typical case, ⅔ values are produced between ten and fifteen years of the company's existence. This is contrary to common sense. Most people - even those who work in startups today - think in the models of the Old Economy, where it is necessary to create values right off the bat. The focus should be on companies with explosive growth in the coming months, quarters or, more rarely, years. This is too short a timeline. Old Economy Models are valid only for Old Economy. This does not work for technology companies and other fast-growing businesses. Nevertheless, the culture of startups today defiantly ignores, if not to say opposing, thinking at intervals of 10-15 years.

PayPal can serve as an excellent illustration. Within 27 months, its growth was 100%. Everyone knew that the growth rate would decline, but still the growth was higher than the discount rate. The plan was that the maximum cost would be reached in the 2011 area. Despite the fact that the discount rate planned in the long-term planning mode turned out to be actually lower, and the growth rates are still at a quite healthy 15%, it is still clear today that the maximum PayPal cost can be expected no earlier than 2020.

LinkedIn is another good example of the importance of a long-term perspective. The market capitalization of this startup is currently about 10 billion dollars, and the shares are involved in trading with a very high P / E of about 850. But the analysis of discounting cash profits gives the following estimate: it is expected that from 2012 to 2019 the cost of the service will reach about 2 billion dollars, while the remaining 8 billion reflect an estimate of 2020 and beyond. LinkedIn evaluation, in other words, makes sense only under long-term conditions, i.e. if the ability to produce values is estimated next decade.

Iii. Durability

People often talk about the “pioneer advantage”. But focusing on this problem has consequences: you can take the first step and disappear. The danger is that you may not just be so immersed in all that to succeed, even if you end up producing values. Leaving the last word behind is even more important than being a pioneer. You must be tuned for long-term presence. In this aspect, business is similar to chess. Grandmaster José Raul Capablanca expressed it this way: in order to succeed, "you must learn the endgame, and then everything else."

Iv. Receiving benefits

The main economic ideas about supply and demand can be used in the arguments about obtaining benefits. A common understanding is that market equilibrium is reached at the point where supply and demand curves intersect. When analyzing a business from this point of view, you get two possible options: perfect competition or monopoly.

In conditions of perfect competition, none of the firms in the industry have any economic profit. If profits appear, then firms enter the market and profits leave. If firms begin to incur losses, they leave the market. So you do not make money. And not only you, nobody earns them. In conditions of perfect competition, the scale of your activity is negligible compared to the scale of the market entirely. You may slightly affect the demand. But, in general, you are in the position of a passive market participant.

But if you are a monopolist, then the whole market is yours. By definition, you are the sole producer of any value. Most economic textbooks spend a lot of time discussing perfect competition. They tend to view examples of monopolies as internal elements or as insignificant exceptions to the situation of perfect competition. The world, as they say in these books, is in a state of equilibrium by default.

But perhaps monopoly is not a strange exception. Perhaps the conditions of perfect competition by default exist only in economic textbooks. Let us doubt whether monopoly is really an alternative to the generally accepted paradigm. Consider the great technology companies. Most of them have one decisive advantage - such as economies of scale or the unique low cost of production - which is at least an important step towards the formation of monopolies. A pharmaceutical company, for example, can use the patent protection of a certain drug, which allows it to trade at a higher price than the cost of manufacturing this drug. Truly valuable enterprises are business monopolists. They promote the production of values that are sustainable in time, and not blurred by the conditions of competition.

V. Competitive ideology

A. PayPal and Competition

PayPal rotated the payment business. This business has significant economies of scale. You could not compete with major credit card companies directly; it was necessary to somehow undermine their foundations. PayPal did this in two ways: through technical innovations and through innovative products.

The main technical problem that had to be solved in PayPal is fraud. When it became possible to make payments via the Internet, much more fraud was revealed than anyone expected. It was also unexpectedly difficult to fight him. There were many different enemies in the “War against Fraud”. For example, there was the Carders World organization, which built a dystopia for the collapse of the foundation of Western Capitalism by anonymous transactions. There was a particularly annoying hacker named Igor, who evaded the FBI outside their area of jurisdiction (Igor was later killed by the Russian mafia). In the end, PayPal was able to create really good software to deal with fraud problems. The name of this software product is “Igor”.

Another key innovation was the reduction of costs for financing sources. For example, the costs of users obtaining information about the status of bank accounts are made up of various factors. But as a result of modeling how much money remained in the account, PayPal can make advance payments, more or less bypass the Automatic Clearing System, and make payments instantly from the user's point of view.

These are just two examples from PayPal. Your business will look different. The conclusion is that it is absolutely important to have some decisive advantage over the existing services that seem to be the best. Because even a small number of competing services quickly creates the basis for a very rapid competitive dynamics.

B. Competition and Monopoly

Whether competition is good or bad is an interesting (and undervalued) question. Most people assume that competition is good. A standard economic narrative focused on perfect competition defines competition as a source of progress. If competition is good, then its opposite is monopoly - it must be bad. Indeed, Adam Smith adopted this view in The Wealth of Nations:

People involved in the same business are rarely found, even in fun and entertainment, but their conversations always end in a conspiracy against society or in search of some price increase mechanisms.

Understanding this point of view is important if only because it is so widespread. But to give a precise definition of why monopoly is bad is hard enough. This, as a rule, is simply taken for granted. But probably it is worth touching on this issue in more detail.

B. Monopoly check

The Sherman Antitrust Act states:

Possession of monopoly power is not illegal if it is not accompanied by elements of anti-competitive behavior.Therefore, in order to understand whether a monopoly is legal or not, we must figure out what “anti-competitive behavior” is.

The Ministry of Justice uses three tests to evaluate monopolies and monopoly prices. The first is the Lerner Index, which gives an idea of the extent to which a particular company has market power. Index value is calculated as:

(price - maximum cost) / price.

The index is measured in the range of values from zero (perfect competition) to one (monopoly). Intuitively, the company's market power means a lot. But in practice, the Lerner index is difficult to estimate, since for this you need to know the market price and the planned maximum cost. Of course, the technology companies themselves know the figures and can independently evaluate their own Lerner index.

The second is the Herfindahl-Hirschman index. It uses the sizes of firms and industries in order to assess how much competition there is in the market. In fact, this is the sum of the squares of the sales share of each firm in the industry. The lower the index value, the more competition in the market. A value below 0.15 indicates a market with a high degree of competition, a value from 0.15 to 0.25 indicates that the market is very saturated. A value of more than 0.25 indicates a high saturation and, possibly, a monopolization of the industry.

And finally, there is still the saturation coefficient of m-firms. You take 4 or 8 of the largest firms in the industry and the amount of their market shares. If together they make up more than 70% of the market, then we can talk about high market saturation.

G. What is good and what is bad in monopoly

First, the minuses: monopolies, as a rule, reduce production volumes and set higher prices than firms in competitive markets. The same statement may not be entirely true for some natural monopolies. In some areas, there is a monopoly of scale, which is slightly different. But, in general, monopolists set prices, and do not respond to demand. Also, monopolies are characterized by the phenomenon of price discrimination, since monopolists can capture a larger market volume by setting different prices for groups of goods. Another object of criticism is the fact that monopolies stifle innovation, because can make a profit as introducing any innovative technologies, and doing without them. Monopoly business will grow without the development of any new technologies.

But you can bring back the argument, also related to innovation. In fact, monopoly can splendidly stimulate innovation. If a company creates each new product significantly better than the previous one, then what's wrong with the fact that the price of this product is higher than the maximum cost of production. The resulting delta is a reward to the creators of new things. A monopolist firm can also afford improved long-term planning and more deeply calculate the financing of the project, since employees have a greater sense of stability than in conditions of perfect competition, where profits are zero.

D. Prejudice of perfect competition

It is interesting to speculate why most people have a firm bias in favor of perfect competition. It is hard to argue with the fact that economists idolize this system. Even the concept of “perfect competition” seems to be related to normative values. We do not call it "insane competition" or "merciless competition." And this is probably not by chance. Perfect competition is claimed to be perfect.

For a start, perfect competition can be attractive because it is easy to model. This probably explains a lot, because the whole economy rests on modeling the real world in order to simplify interaction with it. Perfect competition can also seem like a very meaningful model because it is cost-effective in a static world. Moreover, it is a very popular product from a political point of view, which also does not hurt.

But perfect competition, it is quite expensive. And she seems, perhaps, mentally healthy. All benefits are social, not individual. But people who are really involved in this business have a different point of view - in fact, very many of them want to get real profit. The most serious criticism of perfect competition is that it is meaningless in a dynamic world. If there is no balance - everything constantly moves around - you somehow capture some of the values that you produce. And with perfect competition this is not implied. Perfect competition thus eliminates the question of values - it is hard to conduct business and you can never get anything as a result of this struggle. Contradiction: the more competition, the less chance you have to seize any value.

If you think this way, you can conclude that the concept of "competition" is overrated.Competition can be what we are taught and what we do without question. Maybe you competed with each other in school. Then comes the tougher competition in college and graduate school. And then the rat race in the real world begins. An exact, but hardly unique example of intense professional competition is the competition model of young lawyers from the best law universities in large law firms. You graduate from law school, say, at Stanford, and then you go to work for a big company that pays you really good money. You are working very hard trying to become a partner until you achieve it, although you may not achieve it. The alignment is not in your favor, and, perhaps, you will leave before you even get the chance to make a big break. A startup’s life can be hardbut a little less meaningless in terms of competitiveness. Of course, some people like to compete, no less than in law firms. But such a minority. Ask someone from the majority, and they will say they never want to compete anymore. Of course, winning by a large margin is much better than being in the conditions of merciless competition if you are able to bear it.

. , , , . , . , .

If for the phenomenon of globalization it was necessary to come up with a title, then it would be “The world is flat”. We hear it from time to time, and, indeed, globalization begins with this idea. Technologies, on the contrary, proceed from the idea that the world is Mount Everest. If the world is really flat, then it turns into a crazy competition. Connotations with a negative meaning are suitable for determining, for example, “race for survival”. You must accept a pay cut, because people in China are willing to work for less money. But what if the world is not just crazy competition? What if most of the objects in the world are unique? In high school, we usually have high hopes and ambitions. And too often the college knocks these hopes out of us. People say that they are only small fish in a large ocean.Failure to recognize this is a sign of immaturity. Accepting the truth - that our world is great, and you are only a grain of sand in it - is considered very wise.

, . , , . , , , . , . , , . -, : , . , . — , , . .

The problem is that the ocean is a lot of water, and it is difficult to know exactly what is inside. Perhaps there are monsters and predators that you do not want to meet. You want to stay away from dangerous areas. But you cannot do this if the ocean is too big to control. Of course, you can be the best in your class, even if this class is very large. In the end, someone should be the best. But, nevertheless, the larger the class, the harder it is to become the first number. Therefore, clearly defined, understandable markets are more difficult to master. Therefore, we return to the importance of the question that we formulated in the second paragraph: what companies, the value of whose existence is obvious, no one has yet founded?

E. Venture Investors, Networks and Final Thoughts

Where do venture investment flows go? As a rule, this is not a very big business area. Rather, investors rely on a very limited number of people who are already their representatives. That is, they have access to a unique network of entrepreneurs, this network is the main value, it is supported by relationships. Venture capital is not massive, but personal and often specific. This is directly related to big business. The PayPal network, as it is called, is built on friendships that have formed over a dozen years. This is a kind of franchise. But this is not a unique phenomenon, such a dynamic characterizes, perhaps, all large technology companies, those that represent monopolies in the markets. All of them are not engaged in mass business. Their core is relationships. They create value. They are durable.And they make money.

From the translator:

I ask translation errors and spelling in lichku. I also remind you that this text is a translation, its content is copyright, and the author’s opinion may not coincide with mine.

I repeat once again that I translated 9e9names . Astropilot Editor. All thanks to them.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/155841/

All Articles