E2E (end-to-end) voting system with the possibility of verification by the voter

A few days ago, the course “Securing Digital Democracy” from Coursera and Professor at the University of Michigan Alex Halderman ended.

In this interesting course, Holderman talked about voting requirements, past voting systems, criticized existing systems reasonably, and as a conclusion and advice, he gave an example of technology that he believes is the future (in some places it penetrates into the present).

These are the so-called E2E (end-to-end) systems in which each voter can verify that his vote was correctly counted, and additional checks can be carried out on the correct counting of votes in general.

An important requirement for voting systems is to ensure the anonymity of the voter and the secrecy of his choice. Of course. In addition to these, there are general requirements (for example, availability of voting, authentication, convenience, understandability, etc.), but I will not dwell on them now.

')

Anonymity and secrecy are the problem that needs to be addressed if you want to check how your vote was counted. There are ideas for electoral systems that alleviate this problem by changing the basic principles of voting. For example, “Cloud democracy” from Leonid Volkov and Fyodor Krasheninnikov suggests that a voter can change his voice from one person to another at any moment, must see what decisions his candidate makes, etc. In this case, it makes no sense to hide his voice for the system or for the person behind his back, which removes part of the problem, causing, of course, others, but this is not the topic of this topic.

Under the existing order of things, anonymity and secrecy must be respected. Holderman cited the example of two existing systems that allow, given the above requirements, to provide the possibility of individual verification of voting, "Scantegrity" and "Helios" . These systems are distributed open source, which, according to Holderman, is the best defense against possible vulnerabilities.

Both of these systems use similar principles for encrypting voting results, publishing votes, and checking part of internal data through random selection. For a more detailed description of the process, principles of encryption, etc. You can read the internal documentation or search for additional information on the home pages.

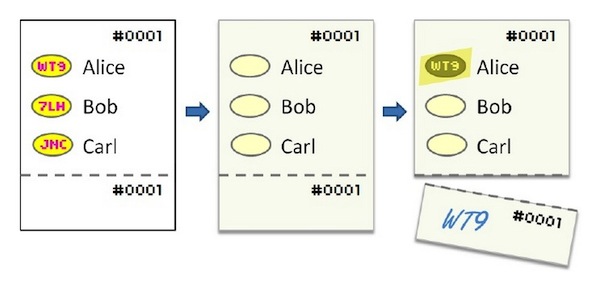

I will describe the process in brief, based on the Scantegrity system. It uses optical scanning systems like our KOIBs, but at the same time provides the user with additional information through hidden tags to select a candidate.

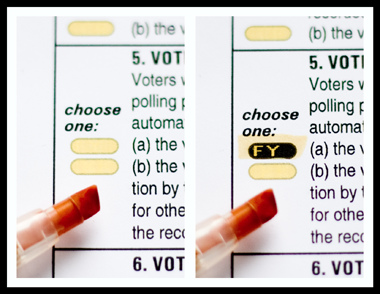

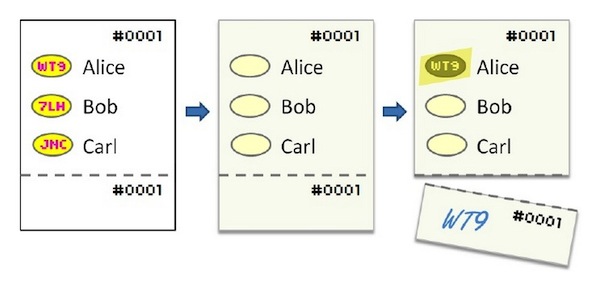

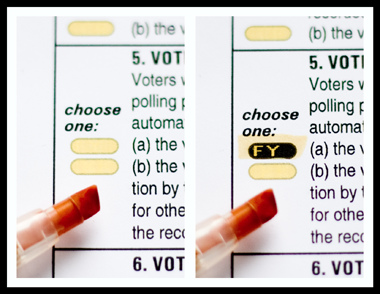

The voter, coming to the site, receives such a ballot with a serial number and a tear-off coupon. In the voting booth, making a choice using a special marker, he reveals hidden information that needs to be rewritten to a tear-off coupon.

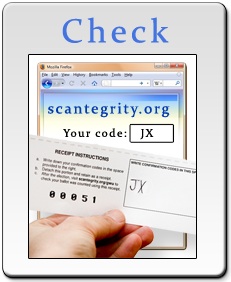

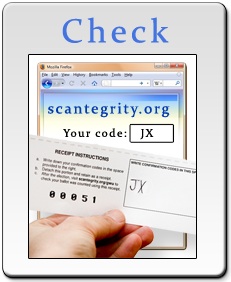

This information (a pair of serial number - code) after the election (or even during the time when optical scanners are connected to the central server) can be checked on a special website, or compared when printing the voting table in the local newspaper.

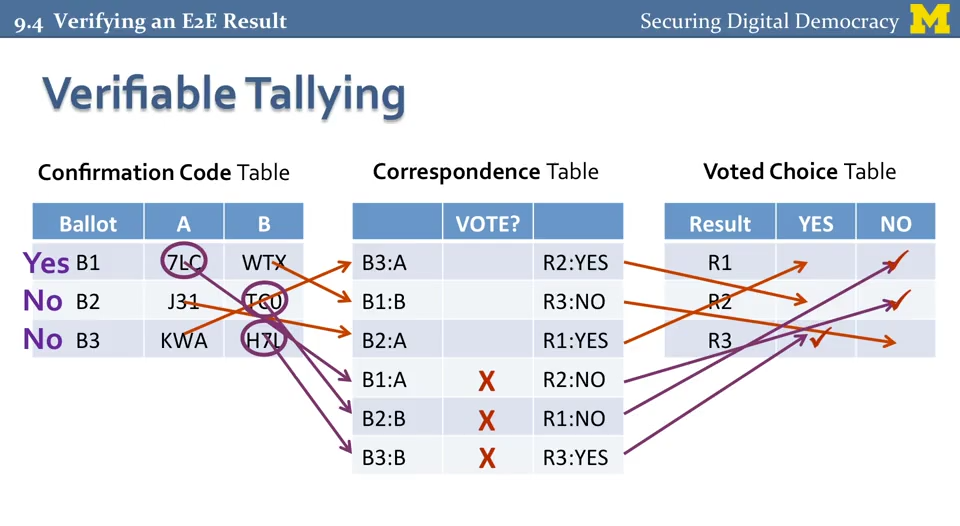

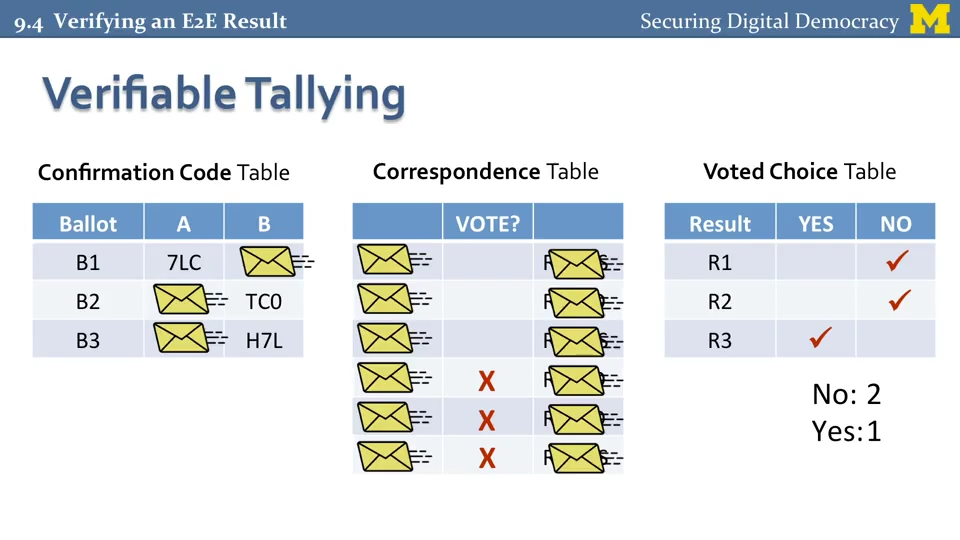

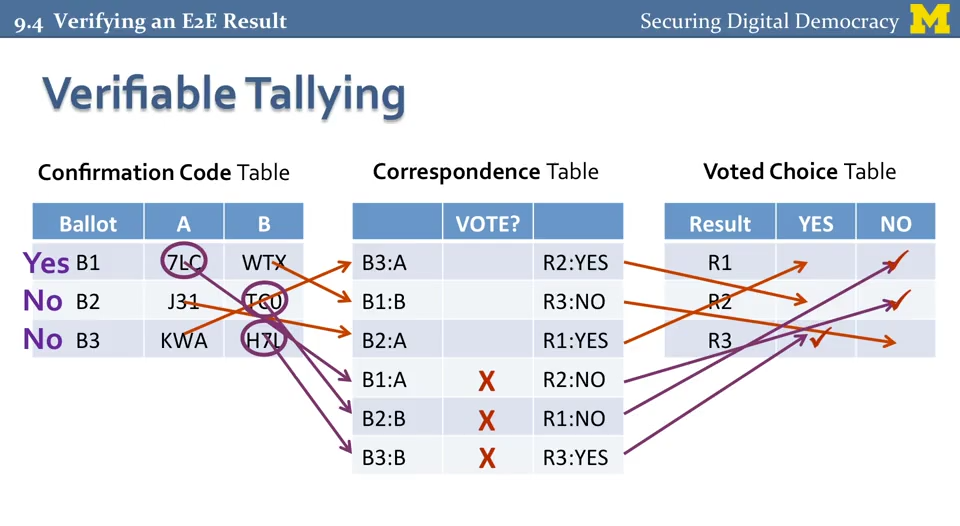

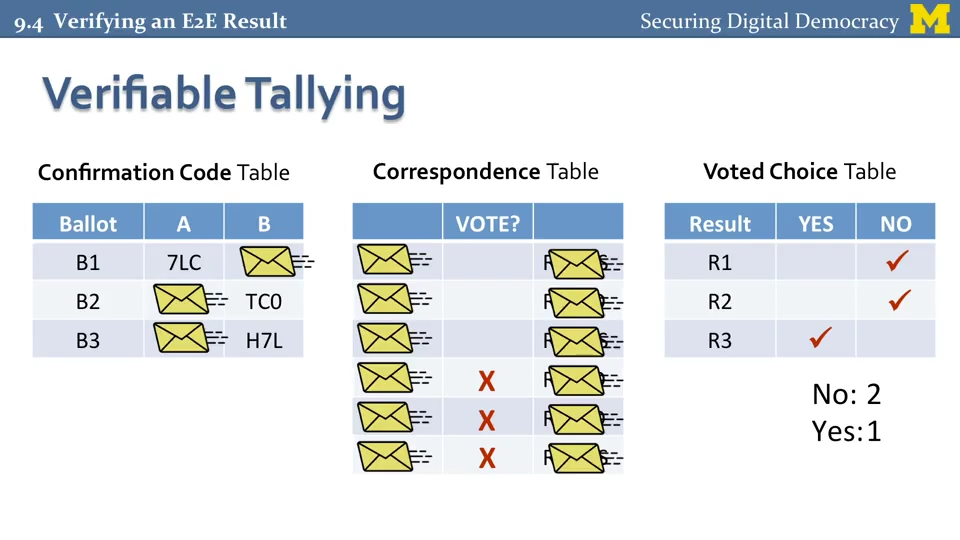

All information received from scanners is recorded in several related encrypted tables.

At the end of the election, the table is randomly decrypted, opening to scan some of the encrypted fields so that the chain for a particular newsletter is not visible (which violates secrecy)

If the correctness of the partially disclosed table is confirmed, that is, the votes were correctly accounted for and correctly reflected in the final table, it can be said with a high degree of probability that there were no internal implementations.

Of course, this does not save us from stuffing, carousels, additional lists and other joys of voting that are common in, let's say, developing countries, but it allows everyone to make sure that their vote is considered correctly, which is already good. Again, there is a certain specificity related to the fact that voting is not just counting. It is also the registration of candidates / parties, as well as equal opportunities for campaigning. In other words, elections must be open, equal and fair. But this is a topic for another conversation.

The Helios system (written in Django), unlike Scantegrity, is designed for relatively small (about 500 voters) voting online, for example, at university elections or other local communities. This is due to the problems of coercion to vote for a particular candidate, the stability of online services to DDoS attacks, and the fundamental inability to materially confirm votes. Holderman believes that technologies currently do not allow reliable online elections to be held at a serious (city or country level) scale, in his opinion, this is a matter of decades, but when problems are solved, the future is definitely E2E online systems. Personally, it seems to me that it will be better to switch to new principles (see “Cloud Democracy”) than to wait until the technology reaches the old principles.

Helios allows you to check whether the system encrypts your voice correctly (by several test attempts with different random keys), whether it records it correctly (instantly, the table ID-encrypted voice is updated immediately and immediately becomes accessible to everyone), and a sample after voting available for audit to everyone.

Unfortunately, in Russia at present, a bunch of election commissions, prosecution offices, investigation courts (which I learned in practice, working as an observer and witness to a crime in the Istrinsky district of the Moscow region, where they stole about 20% of the votes 04.12.2011, stupidly rewriting protocols in more than half of the sections), for which E2E systems, similar to Scantegrity, are unlikely to be interesting. But as time goes on, new people and new ideas will inevitably come, and the E2E voting verification systems will definitely be introduced, sooner or later.

In this interesting course, Holderman talked about voting requirements, past voting systems, criticized existing systems reasonably, and as a conclusion and advice, he gave an example of technology that he believes is the future (in some places it penetrates into the present).

These are the so-called E2E (end-to-end) systems in which each voter can verify that his vote was correctly counted, and additional checks can be carried out on the correct counting of votes in general.

An important requirement for voting systems is to ensure the anonymity of the voter and the secrecy of his choice. Of course. In addition to these, there are general requirements (for example, availability of voting, authentication, convenience, understandability, etc.), but I will not dwell on them now.

')

Anonymity and secrecy are the problem that needs to be addressed if you want to check how your vote was counted. There are ideas for electoral systems that alleviate this problem by changing the basic principles of voting. For example, “Cloud democracy” from Leonid Volkov and Fyodor Krasheninnikov suggests that a voter can change his voice from one person to another at any moment, must see what decisions his candidate makes, etc. In this case, it makes no sense to hide his voice for the system or for the person behind his back, which removes part of the problem, causing, of course, others, but this is not the topic of this topic.

Under the existing order of things, anonymity and secrecy must be respected. Holderman cited the example of two existing systems that allow, given the above requirements, to provide the possibility of individual verification of voting, "Scantegrity" and "Helios" . These systems are distributed open source, which, according to Holderman, is the best defense against possible vulnerabilities.

Both of these systems use similar principles for encrypting voting results, publishing votes, and checking part of internal data through random selection. For a more detailed description of the process, principles of encryption, etc. You can read the internal documentation or search for additional information on the home pages.

I will describe the process in brief, based on the Scantegrity system. It uses optical scanning systems like our KOIBs, but at the same time provides the user with additional information through hidden tags to select a candidate.

The voter, coming to the site, receives such a ballot with a serial number and a tear-off coupon. In the voting booth, making a choice using a special marker, he reveals hidden information that needs to be rewritten to a tear-off coupon.

This information (a pair of serial number - code) after the election (or even during the time when optical scanners are connected to the central server) can be checked on a special website, or compared when printing the voting table in the local newspaper.

All information received from scanners is recorded in several related encrypted tables.

At the end of the election, the table is randomly decrypted, opening to scan some of the encrypted fields so that the chain for a particular newsletter is not visible (which violates secrecy)

If the correctness of the partially disclosed table is confirmed, that is, the votes were correctly accounted for and correctly reflected in the final table, it can be said with a high degree of probability that there were no internal implementations.

Of course, this does not save us from stuffing, carousels, additional lists and other joys of voting that are common in, let's say, developing countries, but it allows everyone to make sure that their vote is considered correctly, which is already good. Again, there is a certain specificity related to the fact that voting is not just counting. It is also the registration of candidates / parties, as well as equal opportunities for campaigning. In other words, elections must be open, equal and fair. But this is a topic for another conversation.

The Helios system (written in Django), unlike Scantegrity, is designed for relatively small (about 500 voters) voting online, for example, at university elections or other local communities. This is due to the problems of coercion to vote for a particular candidate, the stability of online services to DDoS attacks, and the fundamental inability to materially confirm votes. Holderman believes that technologies currently do not allow reliable online elections to be held at a serious (city or country level) scale, in his opinion, this is a matter of decades, but when problems are solved, the future is definitely E2E online systems. Personally, it seems to me that it will be better to switch to new principles (see “Cloud Democracy”) than to wait until the technology reaches the old principles.

Helios allows you to check whether the system encrypts your voice correctly (by several test attempts with different random keys), whether it records it correctly (instantly, the table ID-encrypted voice is updated immediately and immediately becomes accessible to everyone), and a sample after voting available for audit to everyone.

Unfortunately, in Russia at present, a bunch of election commissions, prosecution offices, investigation courts (which I learned in practice, working as an observer and witness to a crime in the Istrinsky district of the Moscow region, where they stole about 20% of the votes 04.12.2011, stupidly rewriting protocols in more than half of the sections), for which E2E systems, similar to Scantegrity, are unlikely to be interesting. But as time goes on, new people and new ideas will inevitably come, and the E2E voting verification systems will definitely be introduced, sooner or later.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/153841/

All Articles