Freedom House has published the report "Freedom on the Internet 2012". Russia at risk

The results of the Freedom House study show that the heat of the struggle for Internet freedom is growing. Governments are increasingly trying to intervene in the life of the network, but also networked civil society, with the support of Internet companies and independent courts, has achieved a number of significant victories.

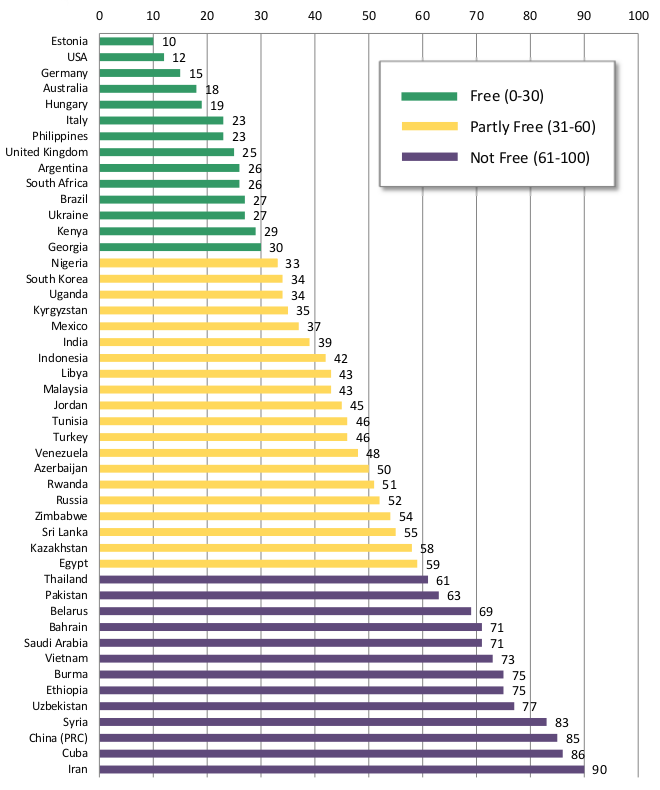

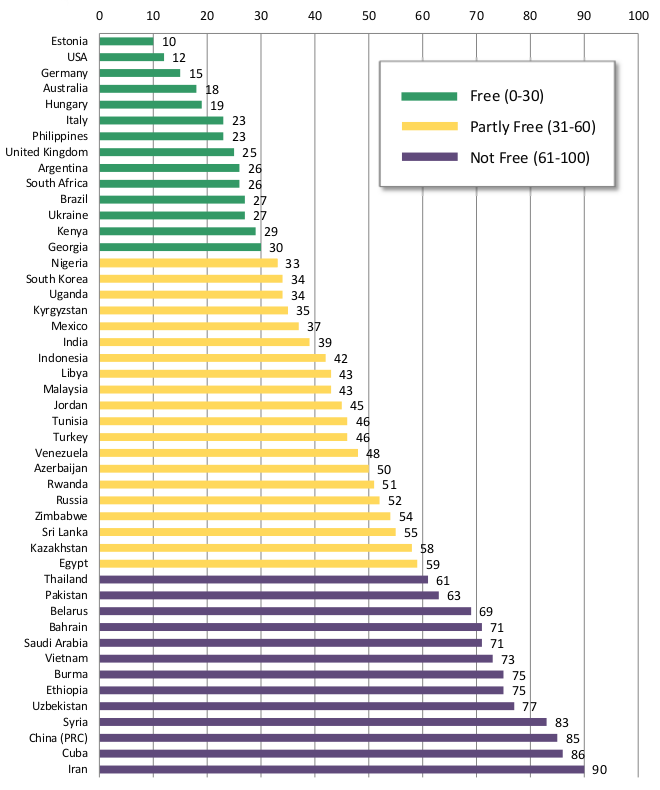

47 countries participated in the ranking. Three main indicators were evaluated - respect for the rights of users, restriction of content distribution (censorship), and infrastructure, legal and economic accessibility of the Internet. On the basis of these indicators, the country exhibited a score from 1 to 100, where 1 is the best result, 100 is the worst. 14 countries deserve free status. Three leaders - Estonia (10 points), USA (12) and Germany (15). Among the countries of the former USSR, Ukraine (27) and Georgia (30) are recognized free except Estonia.

20 countries are partially free. Among them, four CIS countries - Kyrgyzstan (35), Azerbaijan (50), Russia (52) and Kazakhstan (58). 13 countries are not free. The anti-rating leaders are Iran (90), Cuba (86) and China (85). Uzbekistan has 77 points, Belarus has 69 points.

')

17 countries have worsened their results compared to last year. The fastest regress is in Bahrain, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Among the CIS countries, deterioration was demonstrated by Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. Another eight countries - contradictory results. Some indicators have improved, some have worsened. Thus, in Belarus there was a significant increase in the availability of the Internet, the positive effect of which was fully compensated by the equally significant deterioration in the situation with violation of the rights of users. In Estonia and Russia, the restrictions on content have become somewhat tougher, but at the same time, the rights of users have become better respected in Estonia, and in Russia the Internet has become a bit more accessible.

11 countries have improved their results, with Tunisia jumping by as much as 35 points, and Myanmar by 13 points.

According to the rankings, several countries are at a crossroads - attempts to control the Internet are non-systemic, but most conventional media are much more tightly controlled. Due to the growing influence of the Internet and social networks on public life, many of them plan to introduce the “Chinese model” of total control. However, there are real chances that active civil protests can, if not stopped, then slow down this process significantly. Such countries include Russia, Azerbaijan, Libya, Pakistan, Malaysia, Rwanda and Sri Lanka.

The full report in PDF format contains more than six hundred pages with detailed descriptions of cases in each country. Finally, I will cite another interesting graph that allows assessing the relationship between the level of Internet penetration in the country and the degree of its freedom:

Source - Freedom House .

47 countries participated in the ranking. Three main indicators were evaluated - respect for the rights of users, restriction of content distribution (censorship), and infrastructure, legal and economic accessibility of the Internet. On the basis of these indicators, the country exhibited a score from 1 to 100, where 1 is the best result, 100 is the worst. 14 countries deserve free status. Three leaders - Estonia (10 points), USA (12) and Germany (15). Among the countries of the former USSR, Ukraine (27) and Georgia (30) are recognized free except Estonia.

20 countries are partially free. Among them, four CIS countries - Kyrgyzstan (35), Azerbaijan (50), Russia (52) and Kazakhstan (58). 13 countries are not free. The anti-rating leaders are Iran (90), Cuba (86) and China (85). Uzbekistan has 77 points, Belarus has 69 points.

')

17 countries have worsened their results compared to last year. The fastest regress is in Bahrain, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Among the CIS countries, deterioration was demonstrated by Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. Another eight countries - contradictory results. Some indicators have improved, some have worsened. Thus, in Belarus there was a significant increase in the availability of the Internet, the positive effect of which was fully compensated by the equally significant deterioration in the situation with violation of the rights of users. In Estonia and Russia, the restrictions on content have become somewhat tougher, but at the same time, the rights of users have become better respected in Estonia, and in Russia the Internet has become a bit more accessible.

11 countries have improved their results, with Tunisia jumping by as much as 35 points, and Myanmar by 13 points.

According to the rankings, several countries are at a crossroads - attempts to control the Internet are non-systemic, but most conventional media are much more tightly controlled. Due to the growing influence of the Internet and social networks on public life, many of them plan to introduce the “Chinese model” of total control. However, there are real chances that active civil protests can, if not stopped, then slow down this process significantly. Such countries include Russia, Azerbaijan, Libya, Pakistan, Malaysia, Rwanda and Sri Lanka.

Key trends of the modern Internet

- Tighter legislation. In 19 out of 47 countries, since January 2011, laws and directives have been passed that restrict freedom of speech, violate the privacy of users, or persecute people who publish unwanted content for the authorities.

- The pursuit of ordinary users. In 26 of 47 countries, including some democratic ones, there was at least one case of the arrest of a blogger or user for posts and posts on the Internet.

- Violence against government critics. In 19 countries, bloggers and ordinary Internet users were attacked, tortured and abducted as a result of controversial comments on the Internet. In five countries, activists and civilian journalists were killed because of their publications.

- Paid commentators and cyber attacks. Over the past two years, from a relatively rare phenomenon, this has become a mass phenomenon. In 14 countries, cases of coordinated “work” of pro-government commentators on the Internet were noted. In 19 countries, government critics have been hacked and DDoS attacks.

- Increased opportunities for surveillance. In 12 countries, laws were adopted that facilitate surveillance and wiretapping and create opportunities for breaching user privacy.

- Civil resistance is bearing fruit. In 23 countries out of 47 there was at least one case of successful resistance by activists to curtailing freedoms or violating the rights of users. In Europe, a wave of protests led to the failure of the ACTA bill. In Pakistan, non-governmental organizations and activists have played a key role in disclosing and resisting government plans to introduce systematic filtering across the country. In Turkey, demonstrations of protest against the mandatory filtering of “harmful” content for children and other groups of citizens gathered up to 50,000 participants. In the US, it was possible to prevent the adoption of SOPA and PIPA laws. In Hungary and South Korea, constitutional courts blocked some government decisions restricting freedom on the Internet. In countries where there is no independent justice, there have been cases of release from custody by the executive authorities of bloggers and Internet activists as a result of high-profile public protests.

The full report in PDF format contains more than six hundred pages with detailed descriptions of cases in each country. Finally, I will cite another interesting graph that allows assessing the relationship between the level of Internet penetration in the country and the degree of its freedom:

Source - Freedom House .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/152167/

All Articles