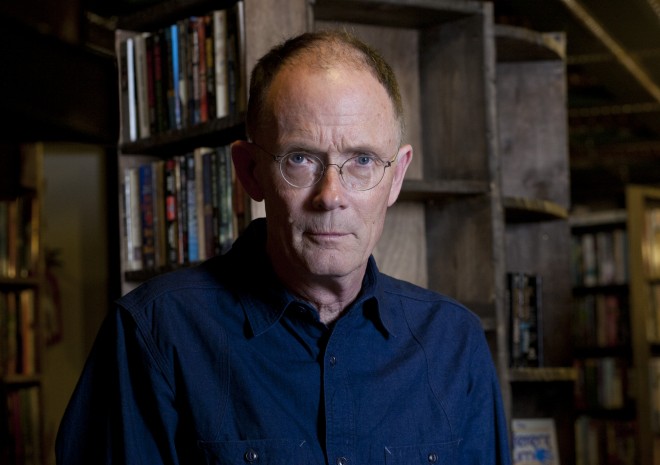

William Gibson Interview Wired. Part 2

The first part is about why science fiction writers almost always misinterpret the future.

One day, William Gibson spent almost five years of his life studying the history of mechanical watches, without any practical purpose, pursuing knowledge for the sake of knowledge. “I wanted to try to become a true otaku in this business,” he explains.

')

Today the author, in the books of which, starting from the classic “Neuromant” of 1984, an imaginary world has grown up, surprisingly echoing modernity, says that he does not have a serious, passionate passion. And free time, which used to go to the old hours, he now holds on Twitter.

In the second part of the interview, one of the most extraordinary science fiction writers and outstanding thinkers talks about the Internet and social media, about his passion for watches and punk rock and why he is afraid of nostalgia.

Wired: You have interesting thoughts about social media. Once you said: “I have never been interested in Facebook and Myspace, because they are too hierarchical. They look like huge supermarkets. Twitter is like a busy street. There you can easily stumble upon anyone. ” Could you tell us more about it?

Gibson: My friend Doug Copeland recently also tweeted something like that. It was about the fact that he once again tried to understand Facebook. He said: “It's like Twitter, only with mandatory homework.” Very appropriate description. With Twitter is easier - you just go there and that's it. And the people around - they just are. No structure and hierarchy - I like it, it is very democratic, and this is lacking in other, more structured social networks. However, in fact it is all at the level of sensations, I am now too hit on abstraction and theory.

Wired: At one time you were addicted to buying vintage mechanical watches on eBay and described this addiction in the article " My Obsession ", which was included in the collection "Distrust That Particular Flavor". What are you obsessed with now? Maybe Twitter?

Gibson: The whole story with the clock was just an experiment on oneself. When I started, I thought that I would never be able to get myself a real, adult hobby, absolutely not connected with anything of what I usually do in life. A hobby that would require an impossibly steep and difficult learning curve. But I did it.

I studied everything connected with the clock for four or five years ... I reached a level that I could already pass for an intelligent and advanced amateur in the company of world-class experts. But by that time I realized that I was not at all interested in collecting any one narrow category of things. This feature of collecting has always been disgusting to me.

I did not want to collect anything. I just wanted for no practical reason to know a lot about one thing. I achieved my goal and almost reached the end of the curve. I felt a pure gratuitous pleasure from the fact that I understand a vast and completely useless field. And this is what ended up for me [laughs]. I didn't have to do this forever. And I never did anything like it again. It was a one-of-a-kind experiment. But it was very cool - I then met many amazingly unusual people.

All this would be impossible if it were not for the Internet. Previously, if you wanted to study something similar in detail, you had to be a complete loony - and travel around the world in search of the same psychos who already studied this subject before you, in order to learn their knowledge. It was so difficult and so dependent on the will of chance that there were few such people.

And now you can live in a remote village in the jungles of Brazil, and decide one morning: “I want to know absolutely everything about a stainless steel sports watch made in the 1950s,” and if you know how to use the Internet, you will be able to master the dissertation in a year protect on this topic. Yes, I knew a lot of people who could.

Maybe now Twitter in some sense has occupied this niche of my time.

Wired: How are the plans for the film adaptation of "Neuromant"? Talk about it is not the first year.

Wired: How are the plans for the film adaptation of "Neuromant"? Talk about it is not the first year.Gibson: I would tell about it only if the idea was finally bent, but since it is not, I don’t want to say anything. I do not like to discuss someone else's unfinished work. She is progressing, that's all. If something out of the ordinary happens, I will write about it on Twitter. Hear anything from other sources - immediately check if I have tweeted about it. If yes, then it is true.

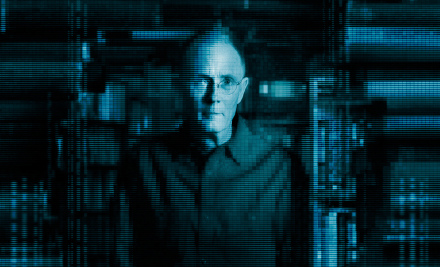

Wired: In the 2000 documentary film “ No Maps for These Territories, ” you made many bold predictions about the technologies of the future, and many of them stood the test of time. You say that you do not believe in the predictive power of science fiction, but it looks like you are well-versed in the future.

Gibson: Maybe ... I don’t know for sure - I only watched the movie once when it came out on the screens to make sure that I didn’t say anything nonsense and that my words weren’t misinterpreted. I suspect that if you saw all the material that did not go into the final version, you would understand that in fact, since the work on the film went for several years, they had the opportunity to choose only those pieces that were confirmed.

This is a common method of playing futurology. Anyone who in one form or another trades in the prediction of the future, be it fiction writers or analysts and advisers, has a strong interest in making their predictions look accurate. If I were absolutely cynical yap, I would also try to convince everyone that I see the future. But in fact, I never wondered whether my predictions would come true or not.

Unfortunately, the predictive power of fiction traditionally occupies an important place in marketing. “Listen to her, she knows the future!” - Old, like the world, the song of a joker. The essence of fiction is not that. Fantasy gives a wonderful set of tools, using which you can disassemble and explore the incomprehensible and ever-changing present in which we live, and which can be quite uncomfortable. This is how I see my work. But an adventurous publisher can see it completely differently.

Wired: Do you think that the popularity of TED and other similar conferences, permeated with a dramatic visionary spirit, has similar roots?

Gibson: Yes, I think the TED phenomenon is based on the same cultural impulses that we just talked about. "Wow! Now they will tell us how everything will be ”... Usually I am not very interested in such things. And they don't invite me to such events often. This is probably for the best.

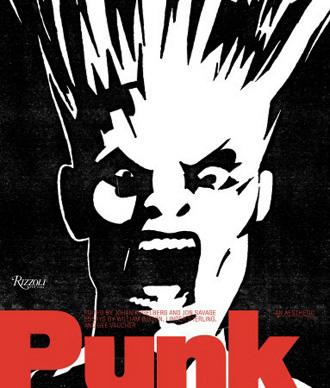

Wired: One of these days is the book " Punk: an aesthetic ", in which there is your essay on the punk culture of the 1970s. I would like to hear your thoughts about music in general and punk rock in particular.

Wired: One of these days is the book " Punk: an aesthetic ", in which there is your essay on the punk culture of the 1970s. I would like to hear your thoughts about music in general and punk rock in particular.Gibson: I'm an old punk, really an old punk [laughs]. I still have a box with a bunch of old records in the basement. There are quite valuable copies that I managed to get with great difficulty. This was a thrill - in that they were hard to get.

Wired: Now listening to music is not so interesting, because you can easily find anything you want?

Gibson: Well, nostalgia is such a disturbing bell for every person. Every time when I find myself thinking about what "X" was before, that it was better than now, or that "Y" is not what I was in my youth, I feel my pulse, checking if I’m sick am i conservatism? [laughs] No, really, throughout the whole history of mankind, suffering voices were heard: “Well, what kind of young people have gone? ... Here we are in their years!” I hear it constantly since it was old enough to pay attention to such and I desperately try to restrain myself not to start grumbling. Because if I do not hold out, then, in a sense, with me will be finished. At least with my ability to predict the future. I hate it when things that I loved are a thing of the past. But if it makes me resist change, then I have problems. That's what I think about it.

What is now is somewhat different from what it was before. But in some ways it remains the same. We just look at it from different points of view. I think that over the past 30 or 40 years there have been fundamental changes with which we still have not really figured out. Because these changes are happening to us, here and now. We are within them, we are unable to cover them entirely. Time will put everything in its place.

I like to compare, - to find a foothold in this cycle - that the British Victorians thought about themselves, and what we think about them now. Because between these two ideas there is nothing at all in common. They probably would have died on the spot if they knew our opinion. They considered themselves the crown of creation. We firmly believe that it is not. From our point of view, they were inferior, flawed and terribly narcissistic. I think that in the same way from the future will look at us. But we are no more able to look at ourselves from the outside than the Victorians were capable of.

This is normal, I just think that this should not be forgotten. And this applies to me too. I do not say that I am special, that I am above the crowd.

Wired: Do you listen to something from modern music? Do you continue to listen to something from the time of your youth - if not with nostalgia, then with emotion?

Gibson: One of the consequences of the onset of the digital era for me personally is that music has become completely timeless. I don’t have a clue and I don’t want to have a clue about what is happening in music now, because now it doesn’t matter. Now, last week, 30 years ago? What's the difference? Everything is on Youtube. So I can discover something ten years late, and I can be one of the first. It is timeless. It is like a long-long calendar for many years at once. And it began a long time ago.

Since the Beatles appeared, not just as a group, but as a cultural phenomenon, like Beatles, parents around the world have been able to observe how their children discover the Beatles. This is still happening. In children, it usually takes about two weeks to swallow them whole. Sometimes longer. And that's it - the Beatles got into them.

In some incomprehensible way, the Beatles live out of time - their image and their records live. This is not 60s music. This is something ... eternal. An amazing thing. Whenever I go in a car and the radio is tuned to some station of classic rock, a fantastic question comes to my mind: “Could I hear the exact same playlist in 2046? Will anyone ever listen to this in 2046? ”Maybe. Will this music ever disappear? In this sense, we are discovering new territories. Maybe…

Wired: Once someone told me that Led Zeppelin looked like sound wallpaper - part of the setting, something inevitable and ubiquitous, almost like furniture.

Gibson: I know this feeling, that's for sure. Take for example "Stairway to Heawen". How much time each of us has heard this song in our lives? Many hours! You could well spend 30 or 40 hours of your life with this music. I hope that at this time you were busy with something pleasant, because this watch will not return. This is a very strange thing that has become familiar to us, but quite surprising for our very recent ancestors.

Wired: What you said about timeless music reminded me of your words about cities. You once said: “In cities, past, present and future can exist side by side. This is a common thing in Europe - not a fantasy, not a fiction. And in the American fiction, the cities of the future are always brand new - until the last inch. ”

Gibson: I think that my attitude towards big cities was shaped by the fact that I grew up outside of them. My childhood was spent in a tiny town away from the megalopolises. Those few really big cities that I visited as a child were completely different. And they are very interested in me. It seemed to me that cities emit rays of television and mass media. And I spent more time in these rays than in real life, and therefore I was happy when I finally managed to leave my little town for the metropolis. I live better and happier in big cities. I'm at ease.

I felt like a black sheep because I liked the big cities, but it seems that most of humanity is moving in the same direction. Every year more and more people move to giant human anthills. The force that draws us to the cities is largely due to the fact that the chances of catching luck are much higher in a big city. Unless, of course, you want to be a farmer or something like that.

The next part is about punk rock, internet memes and Gangnam Style.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/151848/

All Articles