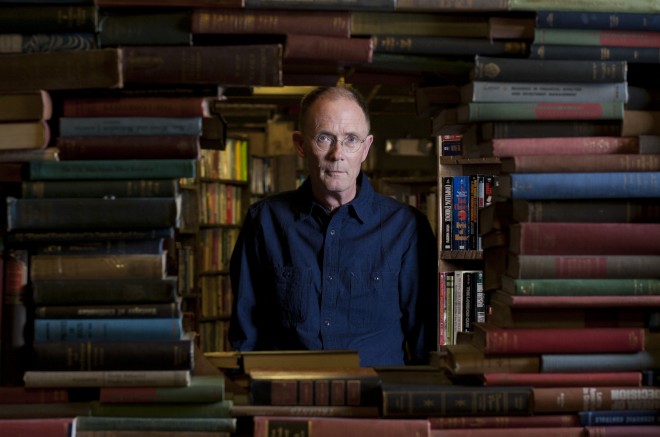

William Gibson Interview Wired. Part 1

It is difficult to find a fantasy so original and possessing such a prophetic gift as William Gibson. The writer himself claims that neither he nor his colleagues have any magical abilities to look into the future.

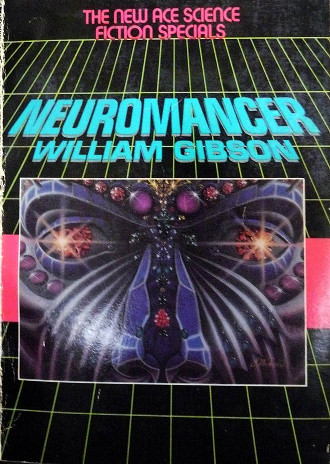

“We are almost always wrong,” he said in a telephone interview with Wired. Gibson - the man who in 1982, in the story “The Burning of Chrome”, came up with the word “cyberspace” itself, and two years later, in the debut novel “Neuromant”, expanded and deepened this concept.

')

In a book that quickly became a classic and a source of inspiration for science fiction writers of the next decades, Gibson predicted that the “consensual hallucination” of cyberspace would be “a daily reality for billions of users in all countries of the world” united into a global network of “unthinkable complexity”.

Since then, Gibson has written many equally successful and well-received critics of novels, including The Count Zero (1986), Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988), The Difference Machine (co-authored with Bruce Stirling, 1990), “Recognizing images ”(2003),“ Zero History ”(2010). Yet Gibson says he was just lucky to create a prophetic description of the digital world. “The fact that“ Neuromant ”describes how the network of the future, the Internet, is in fact quite unlike the real Internet,” he said in an interview.

Gibson’s latest book, a collection of distracting stories called Distrust That Particular Flavor, was released this year; now he is writing a new novel under the working title “The Peripheral”.

In the interview, which will be published in three parts, Gibson touches upon a dizzying range of topics - from vintage watches to comics, from punk rock to visionaries, from internet memes to Neuromant's screen versions.

Wired: Do you think it is worth talking about “science fiction” as a separate genre? In your latest books, for example from the Blue Ant trilogy, the action takes place in a world very close to modern realities.

Gibson: Yes, the plot of each of them unfolds in the year preceding the year of publication. These are books about a hypothetically possible recent past, and not about a hypothetically possible future. They are imbued with the spirit of fiction, but it is not quite fiction. I did it intentionally and deliberately. Well, that is, at the very beginning it was not entirely intentional, but over time the concept has matured and strengthened.

When I was finishing my sixth novel, “All the Parties of Tomorrow,” I was constantly haunted by the feeling that the world around me was so strange and bizarre that I could no longer accurately measure and recognize this constantly surrounding strangeness.

Without the opportunity to experience the “level of quirkiness” of the present, I could not decide how fantastic I should make an imaginary future. That is why the last three books turned out to be the way they came out - I needed a kind of standard of fantasy, with which I could measure the last decade. Judging by the book I'm working on now, I succeeded. I found the strength to build on the basis of the fantastic reality of this even more fantastic world of the future ...

For me the last thing that matters is how accurately fiction predicts the future. Her success in this business is very, very mediocre. If you look at the history of science fiction, the fact that, in the opinion of the writers, it should have happened and what happened in reality - things are very bad. We are almost always wrong. Our reputation as visionaries is based on the ability of people to be amazed when we manage to guess something. Arthur Clark predicted communications satellites and more. Yes, it is amazing when one of us is right, but more often we are mistaken.

If you read a lot of old fiction, as I did, you will definitely see how much we were wrong. I missed much more often than I got to the point. But I was ready for it. I knew about this even before I started writing. Nothing can be done about it.

In a certain sense, if you are not often mistaken when you come up with an imaginary future, then you are simply not trying hard enough. Your imagination does not work to its fullest. Because if you give him the will, you will make mistakes, and make mistakes a lot.

Wired: And yet, people constantly discuss how prophetic "Neuromant" turned out to be, and how accurate your descriptions of the future are.

Wired: And yet, people constantly discuss how prophetic "Neuromant" turned out to be, and how accurate your descriptions of the future are.Gibson: Yes, people often talk about it. It's just that our culture has such a special attitude to predictions. But science fiction writers are not visionaries. In fact, there are no visionaries. They are all crazy or charlatans. However, among science fiction also crazy and charlatans come across, I know a few of them. Just sometimes, if you give yourself free rein to your imagination, look at things with an open mind, it turns out to come up with something that actually happens. When this happens it is beautiful, but there is no magic in it. There are no other words in our language, except magic or magic, with which one can describe the work of science fiction writers and in general everyone who deals with the future.

Sometimes someone on the Internet will take it, and it will call me an “oracle” ... And as soon as the word related to magic was heard, I already know this very well from experience - as soon as someone said “oracle”, that's it! - the word is on everyone's lips, it is repeated endlessly. This is probably good for business. And then I still have a long time to dissuade people that I have a magical prophetic gift ... In fact, if you are not lazy and google everything that is related to William Gibson, you will find tons of texts and posts in which people discuss and discuss how often I was wrong. Where are mobile phones? And neural networks? Why is the Internet so slow in the world of Neuromant? Probably, I myself could have written a good critical article about Neyormant to convince readers that everything is wrong there.

The fact that Neuromant describes how the network of the future, the Internet, is in fact quite unlike the real Internet. I described something. I could not correctly guess what it would be, but I managed to convey the feeling of this “something”. And thanks to this feeling, I beat everyone. The point is not even that other predictions were worse. It’s just that in the early 80s very few science fiction writers paid attention to computer networks. They wrote about something else.

I was lucky, incredibly lucky - I got very excited at the time to write about the digital world. Incredible luck! When I wrote a novel, or rather even earlier, two years before, when I wrote a couple of stories, from which “Neuromant” later grew, from which the whole universe of “Neuromant” all grew up - it took me a week or two to each - I wrote and thought: “Just be in time! If only I had time to publish them before another 20,000 people who are writing exactly the same thing right now, publish theirs! ”Because I thought it was completely banal. I thought: “That's it! The “time of steam engines” has come for such plots.

Do you know what steam time is? People have been making toy steam cars for thousands of years. They were able to make the Greeks. They were able to make the Chinese. Many different nations made them. They knew how to make small metal things spin with steam. No one could ever find any use for this. And suddenly someone in Europe is building a big steam engine in his barn. And the industrial revolution begins. The time has come for steam engines. When I wrote these two stories, I didn’t even know that the coming decades would call the “digital era”. But it was the time of the steam engines. It has come.

Someone in England then started selling books the size of computers. I did not know - and it was not important for me - that in a few years the Casio watch would be more powerful than these computers, it was enough for me that you can buy them today and that they are very small. I thought: “So, over time they will become cheaper and more common. What will people do with them? ”The picture in my head was completely natural and obvious. A few years after that, I didn’t stop being surprised that I didn’t have a huge wave of writers behind me who would crush and swallow me after I opened the floodgates with these little stories about cyberspace. The wave finally came, but it happened later than I expected. It was strange. I greatly benefited from this.

Wired: You recently tweeted that you were planning a new novel, “The Peripheral”. What can you tell us about him?

Gibson: Even on Twitter, I said too much. Twitter is the only place where I was tempted to change my deep, instinctive fear of discussing current work. I can't add anything to what I said there. But since I have blurted it out, I will repeat it here - the novel’s plot develops not just in the future, but in two whole versions of the future. So those who missed all these “Gibsons' tricks” from the future will find in it what they want.

Wired: Are you reading comics now? Once you said that among other things, one French comic was an inspiration for Neuromant.

Wired: Are you reading comics now? Once you said that among other things, one French comic was an inspiration for Neuromant.Gibson: Yes, there was something like that when I was browsing through the English-language editions of Heavy Metal in the corner comic shop. I usually just flipped through them, but did not buy them. Comics were one of the few pleasures in my not-so-rich life. I adored them, like all children at that time. As a teenager, I also loved them, but when I got a little older, my life changed a lot, a lot of things happened and I abandoned my childhood hobby. So I missed the Marvel revolution . When I again felt an interest in them, the era of the underground bands Zap and Robert Crumb was in full swing. After that, I never really enjoyed the comics anymore. If I was born ten or twenty years later, I would surely still love them.

I rarely read comics now. Sometimes I like them, but usually it is because I personally know the author or some of his friends. Recently, it happens less and less. But there are still a lot of comic books around me - at one time my daughter was seriously into indie comics, and she still loves them. True, I suspect that one of the reasons for her such hobbies was that I did not understand anything about them. This is probably correct. When she talks to me about literature, I can't help myself from advice - “Read this, be sure to read this.” Everyone should have their own, exclusive sphere of interest. It is necessary to decide in life.

Wired: What do you think about the fashion of the last years on Hollywood film versions of classic works of fiction? Here, for example, are going to shoot Heinlein's Star Troops again, Kronenberg’s Videodrome will be re-shot ...

Gibson: Really? From the "Videodrome" make an action movie?

Wired: Yes, and it will not shoot Kronenberg.

Gibson: Well ... [laughs] To be honest, I’m less watching Hollywood movies than before. I think the reason is that it turned into a big business, conservative and without risky experiments. Therefore, most often filmed remakes of successful or cult films. From an accounting point of view, this is a safe investment. However, in the last three years there have been more fantastic films that are neither remakes nor blockbusters with a huge budget. I like them and I think they will become classics. I have a hope that we live in an era of interesting, exciting and original films.

Wired: Give some examples.

Gibson: “The Beginning”, although he has, of course, a big budget, “Moon 2112”, “Source Code”, “Hannah” - if only this film can be considered fantastic. I think it is close to this genre. In fact, the complete list is much longer, I just don’t remember everything now. Another "Chimera", for example ...

The second part is about Twitter, vintage watches and Internet addiction.

The third part is about punk rock, internet memes and Gangnam Style.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/151764/

All Articles