ATLAS experiment - a simplified description of the task and a bit about the detector

In the last article I briefly talked about what CERN is doing. Now I want to talk a little bit about the ATLAS experiment.

By tradition, a remark for physicists: I will try to explain everything in a way that is understandable to a person far from physics. I will speak as little as possible in terms of theoretical physics and simplify the Standard Model to disgrace, forgive me Hawking for that.

')

And in order to interest the reader, I will ask one question: why do you have mass?

It would seem a very simple question - everything has a mass, and the mass of an object is the sum of the masses of its components. But no! This is true for macrobodies, but not for elementary particles. For example, a photon has no mass, and that is why it can move at the speed of light. Gluon also has no mass. And, finally, there is no mass in graviton . Notice that a particle (even if it is theoretical) that carries the gravitational interaction has no mass. Actually, the question for which ATLAS wants to get an answer is: what properties does the particle have (and is it a particle at all), responsible for the mass, where does it appear, when does it die, and why does it exist?

In order to understand what the theorists have come to and what experimenters are trying to see at the ATLAS detector, one needs to have a slight idea of the Standard Model - the only model that has no reliable refutations that describes the structure of our Universe and the interaction of bodies in it.

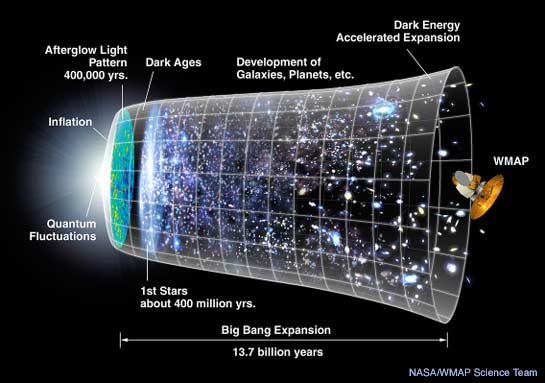

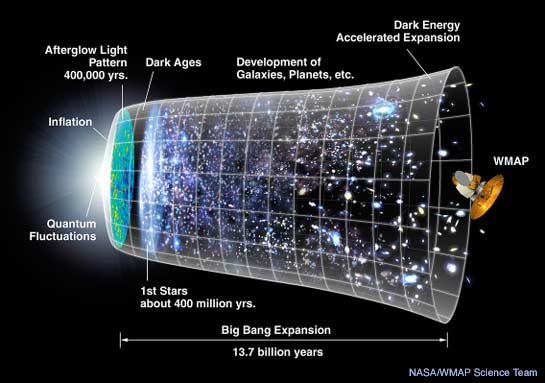

Our Universe was created in the Big Bang about 14 billion years ago. All matter, all energy, time and space, the laws of the interaction of objects with each other were formed there. Now scientists can identify four fundamental interactions:

- Electromagnetic interaction :

The interaction between particles that have a charge. This interaction is inversely proportional to the square of the distance - the further the two objects are, the less they influence each other.

- Gravitational interaction :

The interaction between particles with mass. This interaction is also inversely proportional to the square of the distance.

- Strong interaction :

The interaction between quarks. It is necessary in order to keep quarks in a proton / neutron together.

- Weak interaction :

In particular, it is responsible for the beta decay of the nucleus and allows leptons and quarks to turn into each other. The only interaction that is asymmetric with respect to specular reflection. Very roughly speaking, if I apply a weak interaction to object A and get object B, then the inverse transformation will not work - by applying exactly the same interaction to object B, we will not get object A.

Lyrical digression : in my opinion, now is the time to explain what any physical model is after all. It is necessary to understand that this is just a mathematical theory, just a set of formulas, objects and their names, which are easier for us to operate on. The four interactions mentioned above are just four formulas, the accuracy and accuracy of which is always in question. And physicists, in fact, are trying to make this model more accurate and more convenient, every year, with each new discovery and proof. Ultimately, if we simplify everything very much, we will get a model in which there is only one formula that describes any interaction and any object.

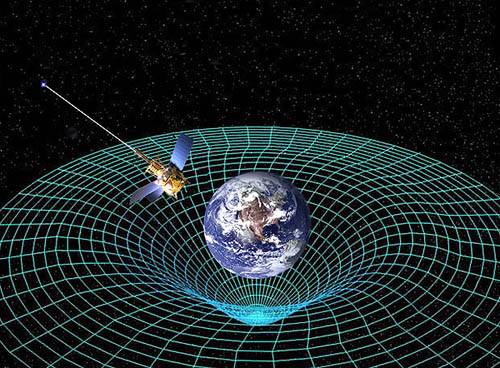

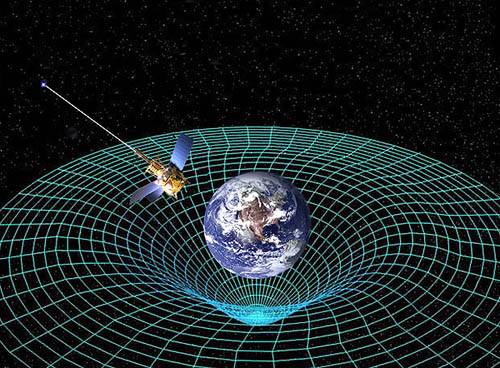

So here. These four interactions between objects should somehow manifest themselves at the micro level. For example, electromagnetic interaction is transmitted using photons: when you put two magnets together, photons fly from them to each other and “inform” that it is necessary to react somehow. And the charge of the body is formed, for example, by electrons (experts, correct, please). The same with mass and gravity - the Higgs boson gives the particle mass, and the curvature of space is responsible for the transfer of the gravitational interaction ( something like that ). And this very boson has not yet been found experimentally, only theoretically calculated. The ATLAS and CMS experiments are trying to “see” it in their detector when two proton beams collide.

This is all related to the question "Why should we look for this boson at all and build such a colossus?"

Then I will try to tell you what was and will be done to achieve this goal.

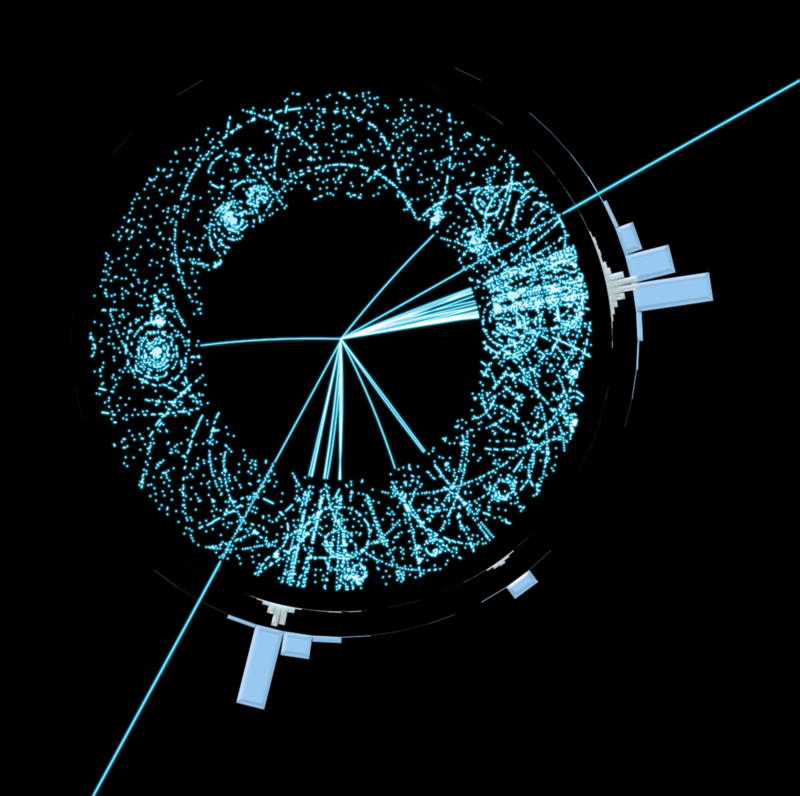

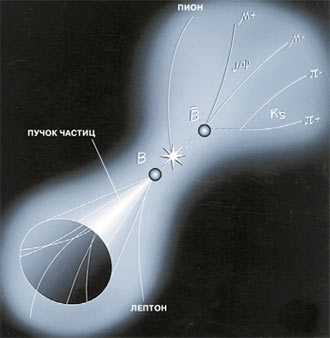

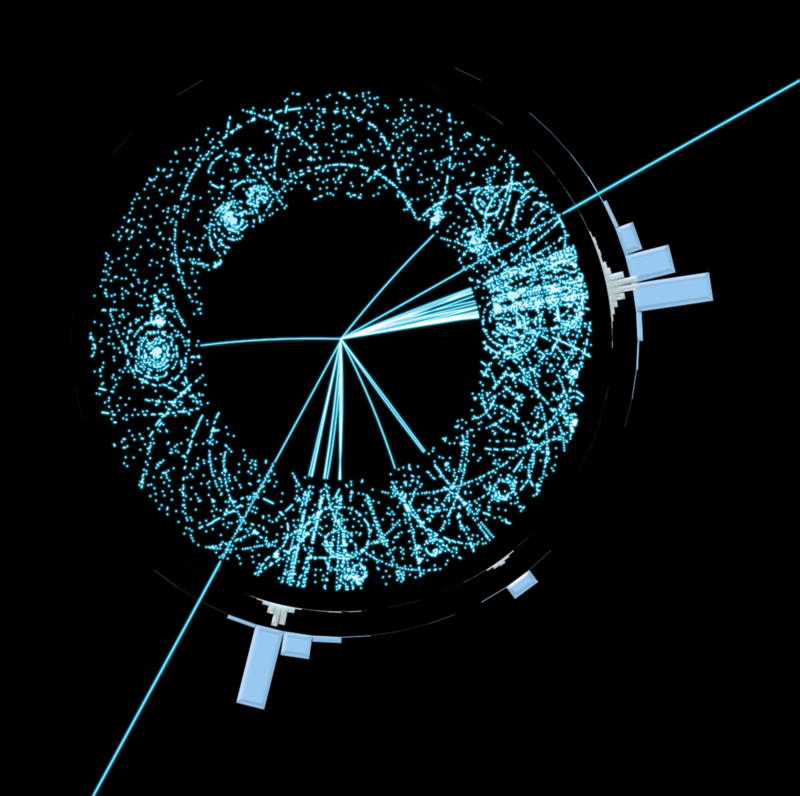

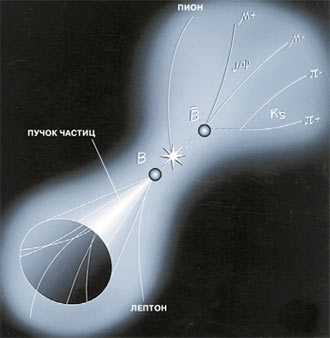

In order to see what still gives mass to the body, it is necessary to break this body. It's very simple - take two beams of protons, accelerate them to near-light speeds and push. How an accelerator works is a separate topic, so I will not raise it here. Collisions occur inside the detector, in our case it is the ATLAS detector. Protons fly apart into smaller particles, which, in turn, can also decompose into smaller particles (for example, the Higgs boson lives too short a time to reach the detector. It dies and produces other particles) that are already detected. And already from this information we can understand what happened immediately after the collision, what particles were born and have already died.

The task of ATLAS and CMS experiments is the same, but they are looking for a solution in different ways. In particular, the ATLAS detector is not very accurate, it works with data obtained from the collision of particles of almost any energy (within the framework of the task, of course) and eliminates a lot of data as unnecessary. However, it works on quantity - it gathers huge statistics of collisions in order to understand what is which. CMS works the other way around for quality. But more about that in a separate article.

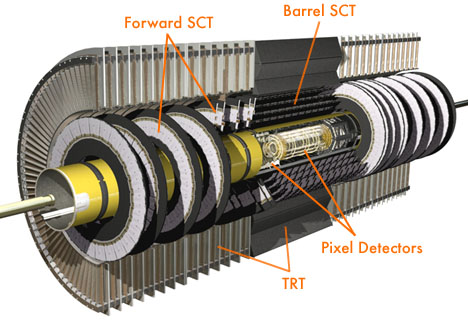

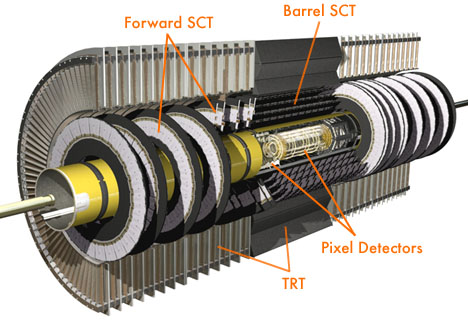

So, the detector. Its structure is also not very complicated (if you do not go into details): around the beam axis (pipes where the beams collide) there are 4 cylinders; external has the following dimensions: length 46 meters, diameter 25 meters, weighing about 7000 tons. To work properly, you need a vacuum inside, and appliances / electronics that work in radiation conditions. Now more about these four layers:

- Internal detector : located closest to the collision point. Serves for the detection of charged particles. Due to the magnetic field inside the detector generated by the magnet around, the internal detector can observe the pulse of a charged particle.

- Calorimeter : Needed to measure particle energy by absorbing them.

- Muon spectrometer : Observes the momentum of muons (which, unfortunately, pass through all other layers intact).

- Magnets : rejects charged particles in order to measure their momentum.

This is the structure of the ATLAS detector, very simplified, somewhat incorrect, but sufficient for a common understanding.

Probably it is worthwhile to briefly describe how we detect particles in general. Here we have a particle flies, and we need to understand what it is and where it comes from. Bubble chambers were one of the first detectors: flying through it, the particle “boiled” water, and we could see its movement in bubbles. Then there were gas detectors - a set of small tubes with gas, and the particle, while flying, charged the gas in one of the tubes, a current passed through it, and we saw where the particle flew. Now in the detectors use much more complex mechanisms, but the essence remains the same: to track the particle track, then to calculate its properties.

I ask everyone to write, answer and ask in the comments. I am pleased to talk with people who work / worked for ATLAS.

By tradition, a remark for physicists: I will try to explain everything in a way that is understandable to a person far from physics. I will speak as little as possible in terms of theoretical physics and simplify the Standard Model to disgrace, forgive me Hawking for that.

')

And in order to interest the reader, I will ask one question: why do you have mass?

It would seem a very simple question - everything has a mass, and the mass of an object is the sum of the masses of its components. But no! This is true for macrobodies, but not for elementary particles. For example, a photon has no mass, and that is why it can move at the speed of light. Gluon also has no mass. And, finally, there is no mass in graviton . Notice that a particle (even if it is theoretical) that carries the gravitational interaction has no mass. Actually, the question for which ATLAS wants to get an answer is: what properties does the particle have (and is it a particle at all), responsible for the mass, where does it appear, when does it die, and why does it exist?

In order to understand what the theorists have come to and what experimenters are trying to see at the ATLAS detector, one needs to have a slight idea of the Standard Model - the only model that has no reliable refutations that describes the structure of our Universe and the interaction of bodies in it.

Our Universe was created in the Big Bang about 14 billion years ago. All matter, all energy, time and space, the laws of the interaction of objects with each other were formed there. Now scientists can identify four fundamental interactions:

- Electromagnetic interaction :

The interaction between particles that have a charge. This interaction is inversely proportional to the square of the distance - the further the two objects are, the less they influence each other.

- Gravitational interaction :

The interaction between particles with mass. This interaction is also inversely proportional to the square of the distance.

- Strong interaction :

The interaction between quarks. It is necessary in order to keep quarks in a proton / neutron together.

- Weak interaction :

In particular, it is responsible for the beta decay of the nucleus and allows leptons and quarks to turn into each other. The only interaction that is asymmetric with respect to specular reflection. Very roughly speaking, if I apply a weak interaction to object A and get object B, then the inverse transformation will not work - by applying exactly the same interaction to object B, we will not get object A.

Lyrical digression : in my opinion, now is the time to explain what any physical model is after all. It is necessary to understand that this is just a mathematical theory, just a set of formulas, objects and their names, which are easier for us to operate on. The four interactions mentioned above are just four formulas, the accuracy and accuracy of which is always in question. And physicists, in fact, are trying to make this model more accurate and more convenient, every year, with each new discovery and proof. Ultimately, if we simplify everything very much, we will get a model in which there is only one formula that describes any interaction and any object.

So here. These four interactions between objects should somehow manifest themselves at the micro level. For example, electromagnetic interaction is transmitted using photons: when you put two magnets together, photons fly from them to each other and “inform” that it is necessary to react somehow. And the charge of the body is formed, for example, by electrons (experts, correct, please). The same with mass and gravity - the Higgs boson gives the particle mass, and the curvature of space is responsible for the transfer of the gravitational interaction ( something like that ). And this very boson has not yet been found experimentally, only theoretically calculated. The ATLAS and CMS experiments are trying to “see” it in their detector when two proton beams collide.

This is all related to the question "Why should we look for this boson at all and build such a colossus?"

Then I will try to tell you what was and will be done to achieve this goal.

In order to see what still gives mass to the body, it is necessary to break this body. It's very simple - take two beams of protons, accelerate them to near-light speeds and push. How an accelerator works is a separate topic, so I will not raise it here. Collisions occur inside the detector, in our case it is the ATLAS detector. Protons fly apart into smaller particles, which, in turn, can also decompose into smaller particles (for example, the Higgs boson lives too short a time to reach the detector. It dies and produces other particles) that are already detected. And already from this information we can understand what happened immediately after the collision, what particles were born and have already died.

The task of ATLAS and CMS experiments is the same, but they are looking for a solution in different ways. In particular, the ATLAS detector is not very accurate, it works with data obtained from the collision of particles of almost any energy (within the framework of the task, of course) and eliminates a lot of data as unnecessary. However, it works on quantity - it gathers huge statistics of collisions in order to understand what is which. CMS works the other way around for quality. But more about that in a separate article.

So, the detector. Its structure is also not very complicated (if you do not go into details): around the beam axis (pipes where the beams collide) there are 4 cylinders; external has the following dimensions: length 46 meters, diameter 25 meters, weighing about 7000 tons. To work properly, you need a vacuum inside, and appliances / electronics that work in radiation conditions. Now more about these four layers:

- Internal detector : located closest to the collision point. Serves for the detection of charged particles. Due to the magnetic field inside the detector generated by the magnet around, the internal detector can observe the pulse of a charged particle.

- Calorimeter : Needed to measure particle energy by absorbing them.

- Muon spectrometer : Observes the momentum of muons (which, unfortunately, pass through all other layers intact).

- Magnets : rejects charged particles in order to measure their momentum.

This is the structure of the ATLAS detector, very simplified, somewhat incorrect, but sufficient for a common understanding.

Probably it is worthwhile to briefly describe how we detect particles in general. Here we have a particle flies, and we need to understand what it is and where it comes from. Bubble chambers were one of the first detectors: flying through it, the particle “boiled” water, and we could see its movement in bubbles. Then there were gas detectors - a set of small tubes with gas, and the particle, while flying, charged the gas in one of the tubes, a current passed through it, and we saw where the particle flew. Now in the detectors use much more complex mechanisms, but the essence remains the same: to track the particle track, then to calculate its properties.

I ask everyone to write, answer and ask in the comments. I am pleased to talk with people who work / worked for ATLAS.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/150032/

All Articles