Data attraction formula

VMware employee Dave McCrory, a specialist in virtualization and cloud computing, has created an unusual model that describes the behavior of data, services and applications on the Internet. He proposed to introduce for the data the concepts of mass and gravity, similar to those used in physics, and even derived a formula for the gravitational interaction between the application and the data. This model is not as insane and senseless as it may seem at first glance - similar gravity models have long been used in economics and sociology, successfully describing the trade turnover between countries and cities, migration and urbanization.

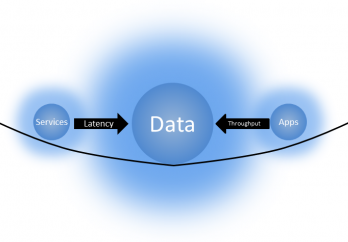

VMware employee Dave McCrory, a specialist in virtualization and cloud computing, has created an unusual model that describes the behavior of data, services and applications on the Internet. He proposed to introduce for the data the concepts of mass and gravity, similar to those used in physics, and even derived a formula for the gravitational interaction between the application and the data. This model is not as insane and senseless as it may seem at first glance - similar gravity models have long been used in economics and sociology, successfully describing the trade turnover between countries and cities, migration and urbanization.Like stars or planets, data clusters attract each other and more lightweight objects, such as applications and services, and the force of this attraction is directly proportional to the mass and inversely proportional to the distance, the analogue of which in the network is the combination of bandwidth and ping. In addition, each pair of “data - application” is characterized by an individual coefficient, depending on how intensively the application requests or generates data. This coefficient is similar to the gravitational constant. Just like for any object in a strong gravitational field, it is necessary to make considerable efforts to “tear” the application from the data, to inform it of a sufficient “escape rate”. Applications and services that work with data seek to reduce delays and expand the channel, approaching data with acceleration, like a stone falling to the ground.

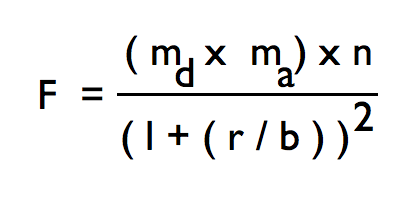

Now the data attraction formula looks like this:

F is the force of attraction in (Mb / s) 2 , m d - the mass of data (MB), m a is the mass of the application (Mb), n is the number of requests per second l - delay (sec), r is the average request size (MB) b - channel width (Mb / s). |

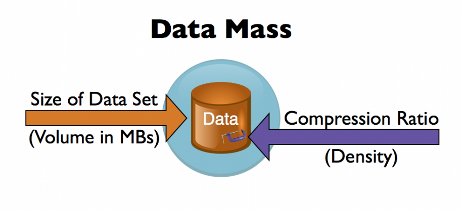

This is not the final version, the author hopes for the help of the community in its improvement and verification. The key values in this formula are the masses of data and applications. They are calculated as follows. The mass of data is the product of their volume in megabytes by density, which is taken as the degree of compression. For example, a database in compressed form takes 5 gigabytes. The compression ratio is 2: 1. Then the mass of this data is 10 GB.

')

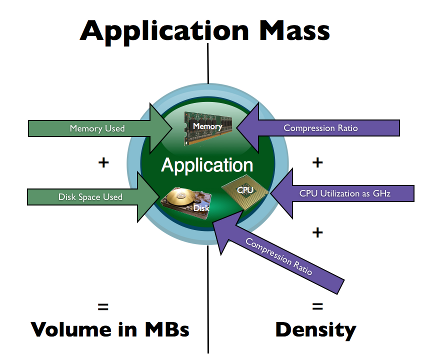

The mass of the application is calculated a little more difficult: the volume used is the amount of RAM used in the process of operation and the space occupied by the program on the disk. To calculate the density, in addition to the compression ratio, which in the case of applications is usually equal to 1, the processor utilization rate measured in gigahertz is used.

From the masses thus calculated and the combination of network characteristics (latency and channel width) and interaction intensity between the application and data (number of requests per second and average request size), which correspond to distance and gravitational constant, we can derive the force of attraction.

According to Dave McCrory, this formula can be used to plan the development of applications and data centers, taking into account gravity. You can express in numbers the portability of the application or the degree of binding to a specific data set, calculate the optimal distribution of data between large data centers and much more.

It is even more interesting to consider more complex combinations of interacting masses, for example, creating buffer masses of data at a short distance from the application, which can greatly reduce the force of attraction by reducing the "gravitational constant" (caching). In addition, there are legal and economic forces in the real world that can significantly strengthen or weaken the gravitational interaction of the masses of data. For example, the high cost of data or application performance greatly increases the force of gravity. Exchange automated trading systems experience such a strong data attraction that they literally “fall” on them, trying to be first in the same data center with them, and then in the same rack.

Many companies and cloud services use tariff policies and legal restrictions to manipulate the force of data attraction in their favor. Some data is secret, some are protected by copyright, some applications and devices are tightly tied by the manufacturer to certain data sets and communication channels. If one succeeds in expanding the data attraction formula so that it describes such situations, an entire theory can be obtained.

The idea of data attraction has already caused some resonance. It all started with one post on the McCrory blog . A number of subsequent posts, their discussion and several publications in online media ( GigaOM , ReadWriteWeb , ZDnet ) led Dave McCrory to create a website entirely dedicated to data attraction.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/147827/

All Articles