Speech, language and music

Disclaimer No. 1 . Last time, I somewhat overdid it with a draft, the result of which was such an epic srach in the comments that I was afraid to look in there, for which I apologize to all who did not answer. I am correcting and citing one good and valid article, which, in fact, was written for another resource, but I am no longer there.

Disclaimer No. 2 This article has nothing to do with Habr's subject, it’s not necessary to write about it in the comments. I do not like the hub "Popular Science" - sign off silently.

I think many of you thought about the meaning of music. Will a representative of a wild tribe understand Beethoven's music? And the medieval inhabitant - the music of the Beatles? How universal is the musical language and why are we able to understand it at all?

')

For a long time I had enough of a vague idea that understanding music was probably the result of my upbringing in the mainstream of European culture. However, at some point I wanted to explore this issue in more detail and I turned to research on this issue.

What was my surprise when I discovered that now in the scientific world there is a real revolution, in the epicenter of which is music! The question of the role of music in human evolution and the relationship between speech and music is one of the hottest topics in modern anthropology; Meanwhile, evolutionary debates seem to be completely overlooked by both professionals (musicologists, performers, composers), and ordinary music lovers. In this article, I will try to give an overview of those bold ideas that have turned the scientific community’s perception of the music and its functions in human society.

Darwin tried to explain the phenomenon of music from an evolutionary point of view (he believed that in humans, music is necessary for men to attract women), by analogy with the marriage songs of animals. During the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, many theories were put forward about the evolutionary sense of music (and, to be honest, all the main thoughts were expressed then), but in the second half of the twentieth century musical questions firmly faded into the background, obscured , much more important problems of language and speech. The idea that music is a late phenomenon in human evolution, essentially a spin-off of speech, an imitation of the intonations of a spoken language, was affirmed. At the same time, it was believed that music and sounds made by animals are different phenomena, having nothing in common with each other. The view of conventional “linguists” regarding music was most fully expressed by John Blacking in his book How musical is man (1973).

The revival of interest in musical themes began in the late 90s. Evolutionists began to realize that existing theories could not explain human musicality. Stephen Pinker, in his book Evolutionary Biology and the Evolution of Language (1997), states: “music is enigma“. In the same year, Niels Wallin, Bjorn Merker and Stephen Brown convened a conference on the origin of music (the reports of this conference in 2000 were published as a separate book, The Origins of Music, available almost entirely in Google books). In 2004, Robin Dunbar, in his book “Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language”, without seriously affecting the music itself, develops an extremely interesting system of views concerning the evolution of human communication. Finally, in 2005, Stephen Miten's famous book about singing Neanderthals ("The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body"), which is the culmination of the "musical" revolution in anthropology, is published.

Unfortunately, the book itself Miten in electronic form is not available. There is a cropped version in googlebooks and a lot of various reviews and reviews.

Many researchers note that language (language) and speech (speech) are completely different concepts; Language as a neurophysiological ability to symbolic thinking arose much earlier than speech. Experiments with "talking" monkeys clearly demonstrate that symbolic thinking has evolved evolutionarily much earlier than the methods of the exchange of symbols between individuals. Speech is thus one of the forms of language representation.

However, speech is not the only such form; there are many other speakers, for example, Morse code, the language of the deaf-mute, the language of the tom-toms, etc. Apparently, speech is the oldest known speaker of the language. But is it the oldest?

The question of the timing of speech is one of the most difficult; The geological chronicle does not contain (and cannot contain) direct evidence of the presence or absence of speech in any fossil ancestors of man.

The upper limit of the period when speech appeared was determined quite precisely - about 40 thousand years ago. During this period, there is a “creative explosion” - a sharp complication of guns (including the emergence of multi-piece guns), the first rock paintings, “Venus figurines”, bone flutes. Knowledge and skills obviously began to accumulate and pass on from generation to generation, which is impossible without speech.

The problem is that the actual man of the modern type - Homo Sapiens - appeared much earlier, about 200 thousand years ago. Apparently, all the prerequisites for the development of speech in sapiens were. If we talk about the ability to pronounce and distinguish sounds, then Homo heidelbergensis (the common ancestors of sapiens and Neanderthals, lived about 400-600 thousand years ago) had a fully developed vocal apparatus. Moreover, it is believed that even Homo ergaster (probably the common ancestor of all Homo heidelbergensis, Neanderthals and sapiens) already had the ability to articulate speech - and he lived about two million years ago! Thus, the estimate of the lower boundary of the period of occurrence of speech in humans extends over millions of years, and there is no reliable data here.

The more interesting is the approach to the question of the appearance of Robin Dunbar's speech, who refuses to attempt to determine the moment of speech directly and considers speech as a social function. Apes (and, obviously, the common ancestors of today's apes and humans), unlike all other social animals, maintain social connections with a full understanding that other members of society are also individuals, with their own vision of the world. Each individual in society creates and maintains its own social network.

(You can read more about the fundamental differences between human society, the Ann-Sally test and political maneuvers of chimpanzees in my older article .)

A means of maintaining a social network in primates is the so-called. grooming - ritual fingering and combing wool from other members of the pack. Grooming allows you to figure out the relationship of one individual to another, to create alliances and alliances.

What, then, allows apes and humans to maintain such social connections? Primates and man are distinguished from other animals by significantly larger brain volumes - and, more specifically, by the size of the neocortex, the new brain cortex. The size of the human brain is 9 times larger than that of other mammals of comparable size.

There is an obvious direct relationship between the size of the group and the neocortex. Meanwhile, no other obvious dependencies between the relative size of the neocortex and other parameters (body weight, occupied territory, diet, etc.) can not be detected. Therefore, the hypothesis that the neocortex is needed by primates and a person primarily to maintain social connections (the more connections you have to maintain simultaneously, the more developed the neocortex) looks, if not completely proven, then at least perfectly consistent with the observed reality.

Interestingly, if this graph is approximated, then the estimated group size for a person is about 150 individuals ( Dunbar number ), which is consistent with the observed data on the size of communities of primitive tribes. At the same time, the maximum group size for chimpanzees — 50 individuals — is about three times smaller. It is curious that, according to Dunbar's observations, the steady size of a talking group is 4 people (large groups begin to break up into several independent conversations), i.e. through speech, a person can maintain contact with three times more interlocutors than a chimpanzee through grooming. It is possible that these two figures coincided by chance, but I personally, following Dunbar, do not think so.

Our distant ancestors, apparently, led a way of life similar to the way of life of modern apes - they were mostly in the trees and fed on fruits, possibly insects or even small mammals. However, about 10 million years ago, a number of climatic and environmental changes occurred, which eventually drove the human ancestors from the forests to the plain.

Big brain requires more energy - more nutritious and easily digestible food. Such food for chimpanzees and other apes is fruits, with ripe fruit. Reduced availability of fruits (both due to climate change and due to competition with other species, in particular, macaques, which are able to eat unripe fruits) led a large group of primates to look for other sources of energy. Great apes move to the edge of the forest zone and spend more and more time on the ground, moving from one group of trees to another along the plain. Probably, this was the reason for the development of upright walking and divided human ancestors, who began to spend much more time on the plain than in the forest, and the ancestors of the current apes (according to molecular-biological data, the separation of gorillas from the future branch of Homo occurred approximately 7 million years ago , chimpanzees - about 5.4), which still prefer the edges of forests.

Savannah is not the safest place for monkeys that do not have sufficient speed to escape from a predator; nor sufficiently large in order not to be afraid of predators; nor enough weapons to become predators themselves. The human ancestors chose another way to deal with the dangers of savanna: actions by an organized group. Predators rarely bind to large groups of animals. Such a group in itself represents a danger to the inhabitants of the savannah, which opens up new sources of food for the group - of animal origin. Most researchers are inclined to believe that distant human ancestors could hardly hunt large animals in an organized way and, rather, were scavengers - a noisy crowd may well ward off even a not too hungry lion from its prey. More energetically beneficial food allows you to further increase the size of the brain - and, consequently, the size of the group. There is a positive feedback, natural selection favors individuals with a large brain, able to live in large groups.

But on this evolutionary path, another limitation arises, a temporary one. The larger the group size, the greater the number of connections each individual maintains, and the more time he is forced to spend on it. Chimps and so are grooming 20% of their time. How much time should the human ancestors spend on him?

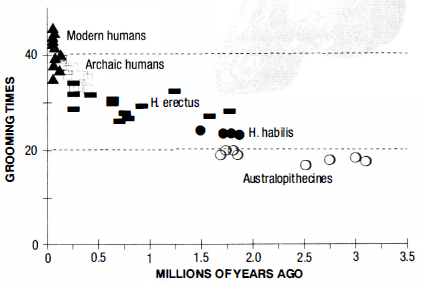

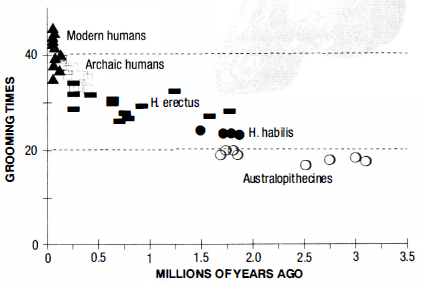

Using data on brain volume and the revealed relationship between the size of the neocortex and the social group, Dunbar was able to build a graph like this:

On this graph, the y-axis represents the time (in percent) that the fossil ancestors of a person were to give to grooming based on the size of their brain. It can be seen that Australopithecus is still quite within the critical 20%, Homo habilis is slightly above this line; but having lived for 1.5 million years, Homo erectus has climbed much higher, to around 30%. It is very unlikely that ancestors of a person could spend so much time on grooming - especially in the conditions of savanna dangers, which requires constant attention.

Therefore, conclusion number one: Homo erectus (and perhaps even Homo habilis) already had other means of social communication than physical grooming. And conclusion number two: the absence of sharp jumps on this graph indicates that there was no sudden invention of speech (a single complex mutation).

Let us formulate the requirements for a new way of social communication, which the ancestors of a person should have developed instead of grooming:

- should allow to identify the person;

- must transmit information about its social status, emotional state and, well, intentions;

- should allow the exchange of information with several other individuals at the same time (due to which the time required for maintaining connections should be reduced);

- it is desirable to leave hands free and allow to communicate in the dark.

As we see, “musical” communication satisfies all the listed criteria. Yes, musical phrases do not carry any specific meaning - but this is not required! A new way of communicating must first of all convey emotional information (emotion = an individual’s attitude to something), and not specific data.

How could our ancient ancestors come to vocal intercourse? In fact, they already had all the necessary prerequisites for this.

Monkeys communicate with the help of sounds. A group of monkeys moving through the forest constantly emit "contact" cries. For a long time it was believed that the only meaning of these shouts was orientation, maintaining the integrity of the group. However, in the early 1980s, Dorothy Cini and Robert Seyfart carefully recorded and examined the cries of monkeys monkeys. And they found that, in addition to orientation, these cries carry a lot of other information, expressed by small but accurate changes in the frequency and volume of the sound. Monkeys have a certain type of cry, issued when approaching a higher-ranking member of the group and a special type of cry when approaching a low-ranking one; there is a special cry, issued when approaching the edge of the forest; there are special cries for warning about various predators - “leopard”, “eagle”, “snake”. If you record such a shout on a tape and reproduce it next to a group of monkeys, the group members will respond exactly in accordance with the meaning of the original shout and with their social status.

Such vocal communication is characteristic not only of monkeys, but also of almost all primates. In fact, great apes "chatter" without stopping. Apparently, being in a very unfriendly environment, our distant ancestors were forced to abandon physical grooming in favor of vocal intercourse.

Another example of monkey vocal activity is “concerts”, which sometimes hold large groups of chimpanzees. Such concerts include screams, stomping, percussion sounds and are performed, most often, before sunset.

Joseph Jordania in the book “Who asked a first question?” Hypothesizes that organized musical activity, like concerts of chimpanzees, was one of those defense mechanisms that helped ancient ancestors of man to defend themselves from predators. Indeed, loud sounds are quite capable enough to embarrass a predator in order to force him to abandon his intentions, and also, perhaps, to leave the already killed prey. The tradition of noisy evening concerts, organized to drive away predators, has been preserved, for example, in some African tribes. Among other things, this kind of group activity rallies the group. Rhythmic organized singing and dancing cause a person to release endorphins - apparently, the attractiveness of this kind was laid genetically at a time when loud singing and stomping was the only weapon of our ancestors against predators.

So, our distant ancestors lived in relatively large groups (60-80 individuals already for Australopithecus, judging by the size of the brain), who were engaged in collecting (fruits, vegetables, tubers) and "active" search fell; most likely, in search of food, such a group had to travel a lot on the savannah (although, probably, groups of trees were the most preferred place to rest and spend the night); to protect against predators, such a group constantly made very loud, rhythmic sounds; With the help of a special kind of shouting, members of the group exchanged information, incl. social.

In such a cacophony of sounds, it is, of course, very difficult to single out individual information flows. Therefore, on the one hand, unsystematic vocalizations should have been structured over time (according to the rhythm and the pitch of the sounds); on the other hand, the members of the group had to eventually develop the ability to analyze very complex sound streams.

And in this moment the theory of "singing Neanderthals" is supplemented with a very convincing evidence. A number of experimenters (first of all, Saffren and Gripenrog, Absolute Pitch in Infant Auditory Learning ) have convincingly shown that babies (up to about 9 months of age) have significantly better ear for music than adults — perhaps even absolute! Infants memorize musical melodies perfectly, recognize them when transposing, and generally demonstrate the skills available to not every professional musician. Absolute hearing is a rudiment inherited from our ancestors. After the invention of speech, the absolute ear turned out to be unnecessary and quickly degraded, but it still remains with a significant part of people; Babies in their development pass through a phase of absolute hearing.

Structuring unsystematic melodies in the course of communication is also confirmed experimentally .

Stephen Miten uses the abbreviation “Hmmmmm” to denote the musical way of sharing information used by human ancestors, Holistic, manipulative, multi-modal, musical, mimetic. According to Miten, art and speech really represent a specifically human phenomenon, but musicality is not. For several million years, the ancient Homo communicated with musical phrases. Homo ergaster inherited from the common ancestors of man and apes limited ability to communicate using sounds; the evolutionary pressure associated with lifestyle changes led ergusters to more intensive use of vocals for communication, which led to the complication of the vocal tract (and, probably, the improvement of the musical ear) and musical phrases. The European branch of the descendants of ergaster - Neanderthals - already possessed a fully developed system of musical communication; the African branch - sapiens - in the course of further development gradually eliminated “H” from “Hmmmmm” - learned to split phrases into words - which ultimately led to the separation of the musical proto-language into two branches: the actual speech (intended to transmit information) and the actual music (intended to convey emotions). (It should be noted that in this moment Zhordania, for example, does not agree with Miten and believes that speech came from the moment when a person learned to clearly articulate sounds, thereby inventing a different, simpler and less exacting auditory ability, to express information by voice.)

In other words, Miten shifted ideas about the relationship of speech and music upside down (or from head to foot, here how to look): it’s not at all music that mimics the intonations of speech - it mimics the intonations of music! (Well, more precisely, the ancient musical proto-language.) And the development of speech did not begin with the invention of words and the compilation of grammars from them - but on the contrary, the integral musical phrase with time began to split into pieces, each of which got its own meaning.

Miten's hypothesis about the joint co-evolution of music and speech from some musical proto-language is confirmed by neurophysiological studies: the areas of the cerebral cortex responsible for music and speech are a series of “blocks” that overlap partially (which indicates their common origin); at the same time non-intersecting blocks are completely equal, i.e. rule out the hypothesis that music is just a by-product of speech development (and vice versa).

The existence of musical universals (in other words, the question of whether the musical phrase is understood by representatives of different civilizations and whether they interpret it the same way) is described in a separate section in the mentioned collection Origins of music. In general, most researchers agree that the understanding of music is partly genetically determined, but it is impossible to specify at least approximately the boundaries of congenital and acquired. A lot of food for thought gives observation of babies. Children under one year perceive musical intervals by ear, while clearly giving preference to consonant intervals, especially pronounced simple numerical relationships (octaves, quints, quarts); at the same time, the newt is perceived as clearly dissonant. Children also clearly prefer the uneven musical scale to be uniform. However, at the same time, children who have the experience of listening to music (parents often sing to them) clearly prefer the standard major scale (two tones - half tone - three tones - half tone); at the same time, children who do not have such experience equally belong to the standard scale and the scale randomly generated from tones and semitones.

Ethnomuscologists also note a number of features inherent, it seems, to the traditional music of all nations. The musical scale is always broken into octaves, and the octaves into steps. The number of steps may vary (generally from 5 to 7). The most primitive songs usually use a limited number of sounds, not more than four. Interestingly, the same is what distinguishes many children's songs. Polyphony is peculiar to most musical cultures. Many of the simplest songs are often built in the form of "question-answer". And, most importantly: it seems that music is peculiar to absolutely all known human communities.

(A large and very detailed account of the forms of musical creativity of a huge number of nationalities is given by Zhordania in Who asked first question? - and as a result of this study, Jordania makes an unequivocal conclusion that polyphony singing preceded monophonic and modern Western civilization, in fact, to a large extent lost the skills of vociferous singing.)

This set of disparate facts gives no idea why and how we understand music. It seems that the theory of Miten allows you to slightly open the veil. If, indeed, musical communication was the main mechanism of social interaction for at least several million years, then we can expect that the reaction to many musical elements is laid genetically. Biomolecular analysis of mitochondrial DNA shows that all modern humans are descended from an extremely small (~ 5000 people are called) groups of sapiens who lived about 200 thousand years ago. Musical language is prone to dialecting as well as colloquial (the researchers believe local dialects are a “friend-foe” marker and are extremely important for the survival of the group), however, it is likely to change orders of magnitude slower than spoken languages - and basic musical elements are still understandable to all mankind.

One such universal musical element is analyzed in detail by Joseph Jordania. He draws attention to the fact that all existing languages in the world use the same intonation to build questions - raising the pitch at the end of a sentence (moreover, in most languages there are constructions that can be either affirmative or interrogative sentences and differ only by changing the pitch - for example, "Let's go." and "Let's go?"). Linguists believe that interrogative intonation is used in expressions with an “open meaning” —the answer of another person is required to complete communication. However, linguists have never been particularly interested in the origin of this intonation, despite its extraordinary versatility.

Jordania traces the origin of this element of communication very deeply - down to our closest relatives, chimpanzees. Chimpanzees make a special, “interested” sound (inquiring pant-hoot); nearby chimpanzees respond to it, so the questioner receives information about who and where is next to him. This "interested" cry of a chimpanzee has a "interrogative" intonation - raising the pitch by the end of the phrase.

Zhordania believes that the ability to ask a question is an exclusively human phenomenon, not peculiar to any of the animals. Despite the fact that "talking" chimpanzees understand the questions addressed to them, including they understand the meaning of interrogative pronouns, they can exactly repeat the question formulated by him for a person - nevertheless, chimpanzees themselves never ask questions to a person. Although in terms of answering questions, the intelligence of a chimpanzee is comparable to the intelligence of a 2.5-year-old child, but in terms of asking questions, any child is qualitatively superior.

It is possible that the appearance of interrogative intonation was the step that allowed the use of sound communication instead of grooming; Our ancient ancestors began to take an active interest in what happens to other members of the pack. A child at the age of ~ 9 months already understands interrogative intonation and is able to reproduce it himself - before he says the first word and, moreover, masters some syntactic constructions, which suggests that interrogative intonation is probably an older phenomenon. than the speech;besides, as we remember, at about the same age, children demonstrate outstanding musical ear.

It is curious that Jordania does not explore another language universality - negative intonation (animals are also incapable of building negative sentences, and children learn negative intonation at about the same age as the interrogative one). I believe her appearance can also be traced to our distant ancestors. The questions of the origin of other marked universals (octaves, uneven scales, consonances and dissonances, the simplest musical forms) - as far as I know, no one has yet studied.

If we accept the hypotheses of Dunbar and Miten, then we can define the meaning of music like this: music is a large emotional-social rebus composed of elements of the first dead language in human history; just like prose is the same kind of rebus, but written in spoken language. Apparently, this is why a person normally perceives genres of art in which heroes do not speak, but sing, including in an unfamiliar language (opera, musical), or even do not utter words (ballet, vocals) - because there are traces in our genetic memory several million years of evolution of our ancestors, during which music was the main and only way to communicate.

- I hereby pass the above text into the public domain.

Disclaimer No. 2 This article has nothing to do with Habr's subject, it’s not necessary to write about it in the comments. I do not like the hub "Popular Science" - sign off silently.

I think many of you thought about the meaning of music. Will a representative of a wild tribe understand Beethoven's music? And the medieval inhabitant - the music of the Beatles? How universal is the musical language and why are we able to understand it at all?

')

For a long time I had enough of a vague idea that understanding music was probably the result of my upbringing in the mainstream of European culture. However, at some point I wanted to explore this issue in more detail and I turned to research on this issue.

What was my surprise when I discovered that now in the scientific world there is a real revolution, in the epicenter of which is music! The question of the role of music in human evolution and the relationship between speech and music is one of the hottest topics in modern anthropology; Meanwhile, evolutionary debates seem to be completely overlooked by both professionals (musicologists, performers, composers), and ordinary music lovers. In this article, I will try to give an overview of those bold ideas that have turned the scientific community’s perception of the music and its functions in human society.

Darwin tried to explain the phenomenon of music from an evolutionary point of view (he believed that in humans, music is necessary for men to attract women), by analogy with the marriage songs of animals. During the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, many theories were put forward about the evolutionary sense of music (and, to be honest, all the main thoughts were expressed then), but in the second half of the twentieth century musical questions firmly faded into the background, obscured , much more important problems of language and speech. The idea that music is a late phenomenon in human evolution, essentially a spin-off of speech, an imitation of the intonations of a spoken language, was affirmed. At the same time, it was believed that music and sounds made by animals are different phenomena, having nothing in common with each other. The view of conventional “linguists” regarding music was most fully expressed by John Blacking in his book How musical is man (1973).

The revival of interest in musical themes began in the late 90s. Evolutionists began to realize that existing theories could not explain human musicality. Stephen Pinker, in his book Evolutionary Biology and the Evolution of Language (1997), states: “music is enigma“. In the same year, Niels Wallin, Bjorn Merker and Stephen Brown convened a conference on the origin of music (the reports of this conference in 2000 were published as a separate book, The Origins of Music, available almost entirely in Google books). In 2004, Robin Dunbar, in his book “Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language”, without seriously affecting the music itself, develops an extremely interesting system of views concerning the evolution of human communication. Finally, in 2005, Stephen Miten's famous book about singing Neanderthals ("The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body"), which is the culmination of the "musical" revolution in anthropology, is published.

Unfortunately, the book itself Miten in electronic form is not available. There is a cropped version in googlebooks and a lot of various reviews and reviews.

Language and speech

Many researchers note that language (language) and speech (speech) are completely different concepts; Language as a neurophysiological ability to symbolic thinking arose much earlier than speech. Experiments with "talking" monkeys clearly demonstrate that symbolic thinking has evolved evolutionarily much earlier than the methods of the exchange of symbols between individuals. Speech is thus one of the forms of language representation.

However, speech is not the only such form; there are many other speakers, for example, Morse code, the language of the deaf-mute, the language of the tom-toms, etc. Apparently, speech is the oldest known speaker of the language. But is it the oldest?

The question of the timing of speech is one of the most difficult; The geological chronicle does not contain (and cannot contain) direct evidence of the presence or absence of speech in any fossil ancestors of man.

The upper limit of the period when speech appeared was determined quite precisely - about 40 thousand years ago. During this period, there is a “creative explosion” - a sharp complication of guns (including the emergence of multi-piece guns), the first rock paintings, “Venus figurines”, bone flutes. Knowledge and skills obviously began to accumulate and pass on from generation to generation, which is impossible without speech.

The problem is that the actual man of the modern type - Homo Sapiens - appeared much earlier, about 200 thousand years ago. Apparently, all the prerequisites for the development of speech in sapiens were. If we talk about the ability to pronounce and distinguish sounds, then Homo heidelbergensis (the common ancestors of sapiens and Neanderthals, lived about 400-600 thousand years ago) had a fully developed vocal apparatus. Moreover, it is believed that even Homo ergaster (probably the common ancestor of all Homo heidelbergensis, Neanderthals and sapiens) already had the ability to articulate speech - and he lived about two million years ago! Thus, the estimate of the lower boundary of the period of occurrence of speech in humans extends over millions of years, and there is no reliable data here.

Socium

The more interesting is the approach to the question of the appearance of Robin Dunbar's speech, who refuses to attempt to determine the moment of speech directly and considers speech as a social function. Apes (and, obviously, the common ancestors of today's apes and humans), unlike all other social animals, maintain social connections with a full understanding that other members of society are also individuals, with their own vision of the world. Each individual in society creates and maintains its own social network.

(You can read more about the fundamental differences between human society, the Ann-Sally test and political maneuvers of chimpanzees in my older article .)

A means of maintaining a social network in primates is the so-called. grooming - ritual fingering and combing wool from other members of the pack. Grooming allows you to figure out the relationship of one individual to another, to create alliances and alliances.

What, then, allows apes and humans to maintain such social connections? Primates and man are distinguished from other animals by significantly larger brain volumes - and, more specifically, by the size of the neocortex, the new brain cortex. The size of the human brain is 9 times larger than that of other mammals of comparable size.

There is an obvious direct relationship between the size of the group and the neocortex. Meanwhile, no other obvious dependencies between the relative size of the neocortex and other parameters (body weight, occupied territory, diet, etc.) can not be detected. Therefore, the hypothesis that the neocortex is needed by primates and a person primarily to maintain social connections (the more connections you have to maintain simultaneously, the more developed the neocortex) looks, if not completely proven, then at least perfectly consistent with the observed reality.

Interestingly, if this graph is approximated, then the estimated group size for a person is about 150 individuals ( Dunbar number ), which is consistent with the observed data on the size of communities of primitive tribes. At the same time, the maximum group size for chimpanzees — 50 individuals — is about three times smaller. It is curious that, according to Dunbar's observations, the steady size of a talking group is 4 people (large groups begin to break up into several independent conversations), i.e. through speech, a person can maintain contact with three times more interlocutors than a chimpanzee through grooming. It is possible that these two figures coincided by chance, but I personally, following Dunbar, do not think so.

Savannah

Our distant ancestors, apparently, led a way of life similar to the way of life of modern apes - they were mostly in the trees and fed on fruits, possibly insects or even small mammals. However, about 10 million years ago, a number of climatic and environmental changes occurred, which eventually drove the human ancestors from the forests to the plain.

Big brain requires more energy - more nutritious and easily digestible food. Such food for chimpanzees and other apes is fruits, with ripe fruit. Reduced availability of fruits (both due to climate change and due to competition with other species, in particular, macaques, which are able to eat unripe fruits) led a large group of primates to look for other sources of energy. Great apes move to the edge of the forest zone and spend more and more time on the ground, moving from one group of trees to another along the plain. Probably, this was the reason for the development of upright walking and divided human ancestors, who began to spend much more time on the plain than in the forest, and the ancestors of the current apes (according to molecular-biological data, the separation of gorillas from the future branch of Homo occurred approximately 7 million years ago , chimpanzees - about 5.4), which still prefer the edges of forests.

Savannah is not the safest place for monkeys that do not have sufficient speed to escape from a predator; nor sufficiently large in order not to be afraid of predators; nor enough weapons to become predators themselves. The human ancestors chose another way to deal with the dangers of savanna: actions by an organized group. Predators rarely bind to large groups of animals. Such a group in itself represents a danger to the inhabitants of the savannah, which opens up new sources of food for the group - of animal origin. Most researchers are inclined to believe that distant human ancestors could hardly hunt large animals in an organized way and, rather, were scavengers - a noisy crowd may well ward off even a not too hungry lion from its prey. More energetically beneficial food allows you to further increase the size of the brain - and, consequently, the size of the group. There is a positive feedback, natural selection favors individuals with a large brain, able to live in large groups.

But on this evolutionary path, another limitation arises, a temporary one. The larger the group size, the greater the number of connections each individual maintains, and the more time he is forced to spend on it. Chimps and so are grooming 20% of their time. How much time should the human ancestors spend on him?

Using data on brain volume and the revealed relationship between the size of the neocortex and the social group, Dunbar was able to build a graph like this:

On this graph, the y-axis represents the time (in percent) that the fossil ancestors of a person were to give to grooming based on the size of their brain. It can be seen that Australopithecus is still quite within the critical 20%, Homo habilis is slightly above this line; but having lived for 1.5 million years, Homo erectus has climbed much higher, to around 30%. It is very unlikely that ancestors of a person could spend so much time on grooming - especially in the conditions of savanna dangers, which requires constant attention.

Therefore, conclusion number one: Homo erectus (and perhaps even Homo habilis) already had other means of social communication than physical grooming. And conclusion number two: the absence of sharp jumps on this graph indicates that there was no sudden invention of speech (a single complex mutation).

Sound and music

Let us formulate the requirements for a new way of social communication, which the ancestors of a person should have developed instead of grooming:

- should allow to identify the person;

- must transmit information about its social status, emotional state and, well, intentions;

- should allow the exchange of information with several other individuals at the same time (due to which the time required for maintaining connections should be reduced);

- it is desirable to leave hands free and allow to communicate in the dark.

As we see, “musical” communication satisfies all the listed criteria. Yes, musical phrases do not carry any specific meaning - but this is not required! A new way of communicating must first of all convey emotional information (emotion = an individual’s attitude to something), and not specific data.

How could our ancient ancestors come to vocal intercourse? In fact, they already had all the necessary prerequisites for this.

Monkeys communicate with the help of sounds. A group of monkeys moving through the forest constantly emit "contact" cries. For a long time it was believed that the only meaning of these shouts was orientation, maintaining the integrity of the group. However, in the early 1980s, Dorothy Cini and Robert Seyfart carefully recorded and examined the cries of monkeys monkeys. And they found that, in addition to orientation, these cries carry a lot of other information, expressed by small but accurate changes in the frequency and volume of the sound. Monkeys have a certain type of cry, issued when approaching a higher-ranking member of the group and a special type of cry when approaching a low-ranking one; there is a special cry, issued when approaching the edge of the forest; there are special cries for warning about various predators - “leopard”, “eagle”, “snake”. If you record such a shout on a tape and reproduce it next to a group of monkeys, the group members will respond exactly in accordance with the meaning of the original shout and with their social status.

Such vocal communication is characteristic not only of monkeys, but also of almost all primates. In fact, great apes "chatter" without stopping. Apparently, being in a very unfriendly environment, our distant ancestors were forced to abandon physical grooming in favor of vocal intercourse.

Another example of monkey vocal activity is “concerts”, which sometimes hold large groups of chimpanzees. Such concerts include screams, stomping, percussion sounds and are performed, most often, before sunset.

Joseph Jordania in the book “Who asked a first question?” Hypothesizes that organized musical activity, like concerts of chimpanzees, was one of those defense mechanisms that helped ancient ancestors of man to defend themselves from predators. Indeed, loud sounds are quite capable enough to embarrass a predator in order to force him to abandon his intentions, and also, perhaps, to leave the already killed prey. The tradition of noisy evening concerts, organized to drive away predators, has been preserved, for example, in some African tribes. Among other things, this kind of group activity rallies the group. Rhythmic organized singing and dancing cause a person to release endorphins - apparently, the attractiveness of this kind was laid genetically at a time when loud singing and stomping was the only weapon of our ancestors against predators.

So, our distant ancestors lived in relatively large groups (60-80 individuals already for Australopithecus, judging by the size of the brain), who were engaged in collecting (fruits, vegetables, tubers) and "active" search fell; most likely, in search of food, such a group had to travel a lot on the savannah (although, probably, groups of trees were the most preferred place to rest and spend the night); to protect against predators, such a group constantly made very loud, rhythmic sounds; With the help of a special kind of shouting, members of the group exchanged information, incl. social.

In such a cacophony of sounds, it is, of course, very difficult to single out individual information flows. Therefore, on the one hand, unsystematic vocalizations should have been structured over time (according to the rhythm and the pitch of the sounds); on the other hand, the members of the group had to eventually develop the ability to analyze very complex sound streams.

And in this moment the theory of "singing Neanderthals" is supplemented with a very convincing evidence. A number of experimenters (first of all, Saffren and Gripenrog, Absolute Pitch in Infant Auditory Learning ) have convincingly shown that babies (up to about 9 months of age) have significantly better ear for music than adults — perhaps even absolute! Infants memorize musical melodies perfectly, recognize them when transposing, and generally demonstrate the skills available to not every professional musician. Absolute hearing is a rudiment inherited from our ancestors. After the invention of speech, the absolute ear turned out to be unnecessary and quickly degraded, but it still remains with a significant part of people; Babies in their development pass through a phase of absolute hearing.

Structuring unsystematic melodies in the course of communication is also confirmed experimentally .

Stephen Miten uses the abbreviation “Hmmmmm” to denote the musical way of sharing information used by human ancestors, Holistic, manipulative, multi-modal, musical, mimetic. According to Miten, art and speech really represent a specifically human phenomenon, but musicality is not. For several million years, the ancient Homo communicated with musical phrases. Homo ergaster inherited from the common ancestors of man and apes limited ability to communicate using sounds; the evolutionary pressure associated with lifestyle changes led ergusters to more intensive use of vocals for communication, which led to the complication of the vocal tract (and, probably, the improvement of the musical ear) and musical phrases. The European branch of the descendants of ergaster - Neanderthals - already possessed a fully developed system of musical communication; the African branch - sapiens - in the course of further development gradually eliminated “H” from “Hmmmmm” - learned to split phrases into words - which ultimately led to the separation of the musical proto-language into two branches: the actual speech (intended to transmit information) and the actual music (intended to convey emotions). (It should be noted that in this moment Zhordania, for example, does not agree with Miten and believes that speech came from the moment when a person learned to clearly articulate sounds, thereby inventing a different, simpler and less exacting auditory ability, to express information by voice.)

In other words, Miten shifted ideas about the relationship of speech and music upside down (or from head to foot, here how to look): it’s not at all music that mimics the intonations of speech - it mimics the intonations of music! (Well, more precisely, the ancient musical proto-language.) And the development of speech did not begin with the invention of words and the compilation of grammars from them - but on the contrary, the integral musical phrase with time began to split into pieces, each of which got its own meaning.

Miten's hypothesis about the joint co-evolution of music and speech from some musical proto-language is confirmed by neurophysiological studies: the areas of the cerebral cortex responsible for music and speech are a series of “blocks” that overlap partially (which indicates their common origin); at the same time non-intersecting blocks are completely equal, i.e. rule out the hypothesis that music is just a by-product of speech development (and vice versa).

Musical universals

The existence of musical universals (in other words, the question of whether the musical phrase is understood by representatives of different civilizations and whether they interpret it the same way) is described in a separate section in the mentioned collection Origins of music. In general, most researchers agree that the understanding of music is partly genetically determined, but it is impossible to specify at least approximately the boundaries of congenital and acquired. A lot of food for thought gives observation of babies. Children under one year perceive musical intervals by ear, while clearly giving preference to consonant intervals, especially pronounced simple numerical relationships (octaves, quints, quarts); at the same time, the newt is perceived as clearly dissonant. Children also clearly prefer the uneven musical scale to be uniform. However, at the same time, children who have the experience of listening to music (parents often sing to them) clearly prefer the standard major scale (two tones - half tone - three tones - half tone); at the same time, children who do not have such experience equally belong to the standard scale and the scale randomly generated from tones and semitones.

Ethnomuscologists also note a number of features inherent, it seems, to the traditional music of all nations. The musical scale is always broken into octaves, and the octaves into steps. The number of steps may vary (generally from 5 to 7). The most primitive songs usually use a limited number of sounds, not more than four. Interestingly, the same is what distinguishes many children's songs. Polyphony is peculiar to most musical cultures. Many of the simplest songs are often built in the form of "question-answer". And, most importantly: it seems that music is peculiar to absolutely all known human communities.

(A large and very detailed account of the forms of musical creativity of a huge number of nationalities is given by Zhordania in Who asked first question? - and as a result of this study, Jordania makes an unequivocal conclusion that polyphony singing preceded monophonic and modern Western civilization, in fact, to a large extent lost the skills of vociferous singing.)

This set of disparate facts gives no idea why and how we understand music. It seems that the theory of Miten allows you to slightly open the veil. If, indeed, musical communication was the main mechanism of social interaction for at least several million years, then we can expect that the reaction to many musical elements is laid genetically. Biomolecular analysis of mitochondrial DNA shows that all modern humans are descended from an extremely small (~ 5000 people are called) groups of sapiens who lived about 200 thousand years ago. Musical language is prone to dialecting as well as colloquial (the researchers believe local dialects are a “friend-foe” marker and are extremely important for the survival of the group), however, it is likely to change orders of magnitude slower than spoken languages - and basic musical elements are still understandable to all mankind.

One such universal musical element is analyzed in detail by Joseph Jordania. He draws attention to the fact that all existing languages in the world use the same intonation to build questions - raising the pitch at the end of a sentence (moreover, in most languages there are constructions that can be either affirmative or interrogative sentences and differ only by changing the pitch - for example, "Let's go." and "Let's go?"). Linguists believe that interrogative intonation is used in expressions with an “open meaning” —the answer of another person is required to complete communication. However, linguists have never been particularly interested in the origin of this intonation, despite its extraordinary versatility.

Jordania traces the origin of this element of communication very deeply - down to our closest relatives, chimpanzees. Chimpanzees make a special, “interested” sound (inquiring pant-hoot); nearby chimpanzees respond to it, so the questioner receives information about who and where is next to him. This "interested" cry of a chimpanzee has a "interrogative" intonation - raising the pitch by the end of the phrase.

Zhordania believes that the ability to ask a question is an exclusively human phenomenon, not peculiar to any of the animals. Despite the fact that "talking" chimpanzees understand the questions addressed to them, including they understand the meaning of interrogative pronouns, they can exactly repeat the question formulated by him for a person - nevertheless, chimpanzees themselves never ask questions to a person. Although in terms of answering questions, the intelligence of a chimpanzee is comparable to the intelligence of a 2.5-year-old child, but in terms of asking questions, any child is qualitatively superior.

It is possible that the appearance of interrogative intonation was the step that allowed the use of sound communication instead of grooming; Our ancient ancestors began to take an active interest in what happens to other members of the pack. A child at the age of ~ 9 months already understands interrogative intonation and is able to reproduce it himself - before he says the first word and, moreover, masters some syntactic constructions, which suggests that interrogative intonation is probably an older phenomenon. than the speech;besides, as we remember, at about the same age, children demonstrate outstanding musical ear.

It is curious that Jordania does not explore another language universality - negative intonation (animals are also incapable of building negative sentences, and children learn negative intonation at about the same age as the interrogative one). I believe her appearance can also be traced to our distant ancestors. The questions of the origin of other marked universals (octaves, uneven scales, consonances and dissonances, the simplest musical forms) - as far as I know, no one has yet studied.

And what is music?

If we accept the hypotheses of Dunbar and Miten, then we can define the meaning of music like this: music is a large emotional-social rebus composed of elements of the first dead language in human history; just like prose is the same kind of rebus, but written in spoken language. Apparently, this is why a person normally perceives genres of art in which heroes do not speak, but sing, including in an unfamiliar language (opera, musical), or even do not utter words (ballet, vocals) - because there are traces in our genetic memory several million years of evolution of our ancestors, during which music was the main and only way to communicate.

- I hereby pass the above text into the public domain.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/147264/

All Articles