Building effective business systems. Chapter 2.2 Business Processes: Local Optimization

At the moment, we have done a tremendous job, identifying the main streams of the company, and arranging them in perfect order. I say "we", because I believe that you are building this scheme with me, and you understand it completely. If this is not the case, then it may make sense to return to the beginning of the document. If this does not bring clarity, then ask the author questions.

But let's leave for the time complicated schemes and return to simple examples. A streamlined approach to business organization allows us to apply simple technical laws to our company, drawing from this a lot of useful lessons.

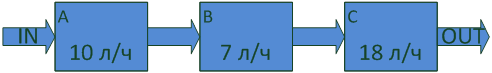

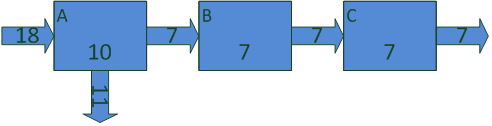

For example, consider a simple system of three tanks and connecting pipes:

Figure 6. The simplest flow-through system with limited bandwidth.

Suppose that through this system it is necessary to drive water. And the more water we chase away, the better. As we see, each of the tanks has its own limitations. Reservoir A only passes 10 liters per hour, B - 7 liters per hour, and C passes 18 liters per hour. Assume that at the beginning of the experiment all the tanks are empty. We deliver water to the IN pipe at a pressure of 18 l / h. Attention question:

How fast will water flow out of the OUT pipe?

')

There are several ways to get an answer: calculate the average of all tanks, take the largest number, take the smallest number, and other arithmetic operations. The correct answer is only one - 7 liters per hour. The old saying goes: "The chain is as strong as its weakest link." (Remember the conclusion about the laws common to all systems?) Water will flow through the system at the speed with which the slowest reservoir can pass it, which means 7 liters per hour. What do you think will happen if you continue to supply water with a pressure greater than 7 l / h? If you have never “stoked” your neighbors, then I inform you: either it will break the pipe or it will break the tank.

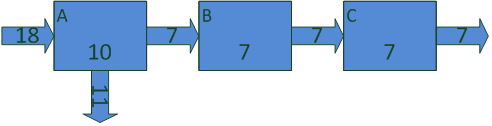

To avoid a tragedy, add a branch pipe, which will discharge excess water. In the diagram, we denote the actual speed of water passing through the system:

Figure 7. Actual water flow rate.

From the diagram it can be seen that 11 liters per hour flows out of the system to nowhere. I think, colleagues, you have already drawn analogies between this simple picture and our flow chart of the company. Imagine that this diagram depicts three departments of our company: "Sales - Production Managers - Workshop". No matter how much force salespeople spend on enhancing the incoming flow, more than the slowest department will work, it will not pass through the company.

Let's look at another simple example. Let's build the flow diagram of the assembly of some product, consisting of three posts and a conveyor belt between them.

Figure 8. Production Flow.

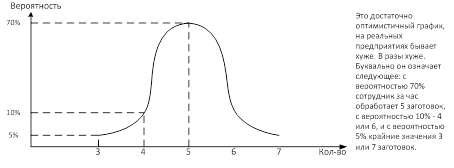

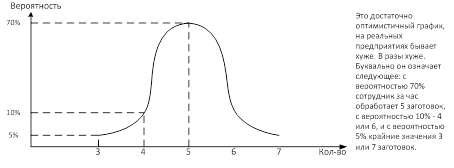

On the production line is fed 5 blanks that must be processed to get 5 finished products. But at the same time, it should be remembered that real people are on the posts and sometimes they are distracted, tired or just lazy. In such cases, they will process up to 3 in an hour instead of 5 blanks. But then they realize that they are lagging behind the plan and quickly catch up, making up to 7 blanks. To be fair, we will distribute the processing probability in such a way that the average output remains at level 5:

Figure 9. The probability of processing a different number of blanks.

And, of course, the question:

How many units of finished products will be produced during the forty-hour work week?

Production managers are required to take it every day in the mind and very quickly. Try it and you, first count, and then look back.

Table 1. Actual production of the production chain.

Let me remind you that the production plan for all is five, and the table contains what the employee has planned for himself. As you can see, we lost 10% of productivity only on the fact that workers sometimes deviate from the production rate! Let's look at how this happened.

Table 2. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 1).

For example, in the very first hour, Vasily, instead of the required five blanks, processed four. Of course, two hours later he caught up with a lag, making six instead of five, but in the first hour he transferred only four to the next post. What happened at this time in the second post? Peter, acting in normal mode, was forced to periodically wait for work, since Vasily did not give it quickly enough. Thus, from Peter to Nicholas also took four blanks instead of five, and the output in the first hour amounted to four units of production.

Table 3. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 2).

I’ll remind you again that live people are standing by the conveyor. They all want to get paid, to please their children and live comfortably. Therefore, at the third hour the situation may well look like this:

Peter, he remembers that he is already lagging behind the production rate, and decided to catch up with the backlog, and also to do a little for the future. For this reason, he planned to work as fast as possible and to make 7 blanks. But Vasily had important things to do, and thinking about them, he did even less than in the first hour. How do you think, how polite will Peter and Vasily be for the whole hour, which he will have to work in a tense manner, but at the same time systematically receive less work? And given that this is not the first time?

Every time when you see conflicts in the company on the subject “What the hell is so long !?”, you observe local Basil and Peter.

In both of the examples reviewed, the first link performs less than planned, so the following links also give less output. But what will happen if the first link exceeds the plan?

Table 4. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 3).

As can be seen from the table, nothing will change. In general, the whole chain will work only with normal output. Even Nikolai’s intention to over-fulfill the plan will not help either. Here is how it looks in practice:

Basil, catching up with the backlog, accelerates his work, making 7 blanks. But Peter at the same time is ready to do only his own norm - Vasily’s problems do not interest him (and after conflicts at the beginning of work, he is even a little pleased with his difficulties). Peter works with a normal production of 5 units. Where should Vasily take the extra two blanks? As a rule - they are placed next to the workplace, giving rise to a huge pile of work in progress. Every time the previous link does more than it can accept the next, the surplus goes into inventory. In general, not so scary when it comes to stocks of steel bars, which for years may lie in the aisle between the machines. And if we are talking about perishable blanks, which can now be processed, and in an hour they are no longer suitable?

The first time we encountered a change in the direction of flow in the example of tanks and water. From this example we can draw the following conclusion:

When one of the divisions tries to do more work than the next can accept, the surplus goes to stock.

The second production chain example confirms our conclusion and gives us another one that looks like this:

Fluctuations in the productivity of links reduce the productivity of the entire system, generating stocks.

Both of these conclusions (or system laws) work “excellently” next to each other. I leave to you a problem for independent decision:

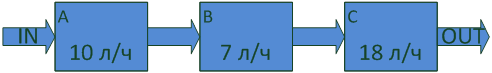

Figure 10. The effect of two laws on the system.

Question:

What is the productivity of the system shown in Figure 10?

I will not give an answer to this question here, but ask a few more. Imagine that Vasily is our salesman. The figure shows that its performance is higher than that of Peter. (I do not presume to say now that this is the case in reality, this is only a model.) Do you think, colleagues, can Vasily divert the incoming customer flow "to the reserve"? No, he can not! A client is a very rapidly deteriorating piece, the passage of which, even within a few minutes, may make it unsuitable for further use.

Now that we have dealt with the streaming systems and some laws in force on them, I am ready to explain my remark in the first chapter about efficiency and loading at 100%. If you force Vasily, Peter and Nicholas to work at full capacity, we will achieve an increase in the number of unfinished work, the departure of dissatisfied customers and conflicts between employees, but not an increase in the efficiency of the entire system.

The “all work at 100%” approach is the local optimization, and from the above, one important conclusion can be made:

Local optimization is bad!

I will cite typical problems for “locally optimized” companies explaining why this is bad:

Problem number 1 : Inefficient use of resources. The head of each of the units, seeking to improve the efficiency of their department, invests strength, money and other resources. Salespeople spend forces on attracting new customers with whom there is no one to work, production purchases materials that will be needed very soon, buyers send goods to the company that are “interesting” at a price, but unnecessary in the market, etc.

Problem number 2 : Constant conflicts in the team. I have already described several conflict situations above, and they all have a common nature of occurrence: within the framework of their department, each employee works best (or, at least, not bad), but from the point of view of employees of other departments, he creates problems.

Problem number 3 : Departure from the work plan and the delay of employees at the workplace at the end of the day Inventories of unfinished work need to rake. At the factories, this is due to the fact that at some moment the blanks in the aisle block it completely, and in our work it looks like a manager's plan, which lacks space. And this causes the following problem.

Problem number 4 : Overall decline in work efficiency. An employee who has more tasks than he should be forced to constantly switch between them. Switching between tasks requires additional time. Moreover, time is spent both on immersing directly into the task left before, and on trying to explain to a colleague requiring it, that another problem that is more important for the company is being solved.

Problem number 5 : Cash gaps. This problem should be described in the “Finance” section, but its causes are also found here. Chaotic spending of funds (as tasks are performed, and resources are spent on them) negates the possibility of planning. And there are constantly situations in which tasks that need to be solved in a week have already been paid, and there is nothing to buy materials for today's work.

It should be noted here that there are not only problems number 3 and number 4. As systemic problems, they are also interconnected into the system. Figure 11 shows a fragment of the problem system that haunts us day after day:

Figure 11. A fragment of the company's problems system.

In order not to make me sad, I brought only a part of the network of problems. If you do not believe, answer the question: “How does the systematic non-fulfillment of plans for relations with clients affect?” Or “How does labor efficiency affect the salaries of employees?”

Effective managers in this place should say: “So let's list all the problems and solve them!” An excellent proposal, but, unfortunately, completely useless. Solving each of these problems separately and even in small groups is nothing but another local optimization.

UPD`17:

I still can not get together to republish the material. If someone really needs or just wondering, here is a link to the original. Please only one: when used in full or in part, indicate the link to the author. All coordinates are in profile .

But let's leave for the time complicated schemes and return to simple examples. A streamlined approach to business organization allows us to apply simple technical laws to our company, drawing from this a lot of useful lessons.

Previous chapters

For example, consider a simple system of three tanks and connecting pipes:

Figure 6. The simplest flow-through system with limited bandwidth.

Suppose that through this system it is necessary to drive water. And the more water we chase away, the better. As we see, each of the tanks has its own limitations. Reservoir A only passes 10 liters per hour, B - 7 liters per hour, and C passes 18 liters per hour. Assume that at the beginning of the experiment all the tanks are empty. We deliver water to the IN pipe at a pressure of 18 l / h. Attention question:

How fast will water flow out of the OUT pipe?

')

There are several ways to get an answer: calculate the average of all tanks, take the largest number, take the smallest number, and other arithmetic operations. The correct answer is only one - 7 liters per hour. The old saying goes: "The chain is as strong as its weakest link." (Remember the conclusion about the laws common to all systems?) Water will flow through the system at the speed with which the slowest reservoir can pass it, which means 7 liters per hour. What do you think will happen if you continue to supply water with a pressure greater than 7 l / h? If you have never “stoked” your neighbors, then I inform you: either it will break the pipe or it will break the tank.

To avoid a tragedy, add a branch pipe, which will discharge excess water. In the diagram, we denote the actual speed of water passing through the system:

Figure 7. Actual water flow rate.

From the diagram it can be seen that 11 liters per hour flows out of the system to nowhere. I think, colleagues, you have already drawn analogies between this simple picture and our flow chart of the company. Imagine that this diagram depicts three departments of our company: "Sales - Production Managers - Workshop". No matter how much force salespeople spend on enhancing the incoming flow, more than the slowest department will work, it will not pass through the company.

Let's look at another simple example. Let's build the flow diagram of the assembly of some product, consisting of three posts and a conveyor belt between them.

Figure 8. Production Flow.

On the production line is fed 5 blanks that must be processed to get 5 finished products. But at the same time, it should be remembered that real people are on the posts and sometimes they are distracted, tired or just lazy. In such cases, they will process up to 3 in an hour instead of 5 blanks. But then they realize that they are lagging behind the plan and quickly catch up, making up to 7 blanks. To be fair, we will distribute the processing probability in such a way that the average output remains at level 5:

Figure 9. The probability of processing a different number of blanks.

And, of course, the question:

How many units of finished products will be produced during the forty-hour work week?

Production managers are required to take it every day in the mind and very quickly. Try it and you, first count, and then look back.

Table 1. Actual production of the production chain.

Let me remind you that the production plan for all is five, and the table contains what the employee has planned for himself. As you can see, we lost 10% of productivity only on the fact that workers sometimes deviate from the production rate! Let's look at how this happened.

Table 2. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 1).

For example, in the very first hour, Vasily, instead of the required five blanks, processed four. Of course, two hours later he caught up with a lag, making six instead of five, but in the first hour he transferred only four to the next post. What happened at this time in the second post? Peter, acting in normal mode, was forced to periodically wait for work, since Vasily did not give it quickly enough. Thus, from Peter to Nicholas also took four blanks instead of five, and the output in the first hour amounted to four units of production.

Table 3. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 2).

I’ll remind you again that live people are standing by the conveyor. They all want to get paid, to please their children and live comfortably. Therefore, at the third hour the situation may well look like this:

Peter, he remembers that he is already lagging behind the production rate, and decided to catch up with the backlog, and also to do a little for the future. For this reason, he planned to work as fast as possible and to make 7 blanks. But Vasily had important things to do, and thinking about them, he did even less than in the first hour. How do you think, how polite will Peter and Vasily be for the whole hour, which he will have to work in a tense manner, but at the same time systematically receive less work? And given that this is not the first time?

Every time when you see conflicts in the company on the subject “What the hell is so long !?”, you observe local Basil and Peter.

In both of the examples reviewed, the first link performs less than planned, so the following links also give less output. But what will happen if the first link exceeds the plan?

Table 4. Actual production of the production chain (Fragment 3).

As can be seen from the table, nothing will change. In general, the whole chain will work only with normal output. Even Nikolai’s intention to over-fulfill the plan will not help either. Here is how it looks in practice:

Basil, catching up with the backlog, accelerates his work, making 7 blanks. But Peter at the same time is ready to do only his own norm - Vasily’s problems do not interest him (and after conflicts at the beginning of work, he is even a little pleased with his difficulties). Peter works with a normal production of 5 units. Where should Vasily take the extra two blanks? As a rule - they are placed next to the workplace, giving rise to a huge pile of work in progress. Every time the previous link does more than it can accept the next, the surplus goes into inventory. In general, not so scary when it comes to stocks of steel bars, which for years may lie in the aisle between the machines. And if we are talking about perishable blanks, which can now be processed, and in an hour they are no longer suitable?

The first time we encountered a change in the direction of flow in the example of tanks and water. From this example we can draw the following conclusion:

When one of the divisions tries to do more work than the next can accept, the surplus goes to stock.

The second production chain example confirms our conclusion and gives us another one that looks like this:

Fluctuations in the productivity of links reduce the productivity of the entire system, generating stocks.

Both of these conclusions (or system laws) work “excellently” next to each other. I leave to you a problem for independent decision:

Figure 10. The effect of two laws on the system.

Question:

What is the productivity of the system shown in Figure 10?

I will not give an answer to this question here, but ask a few more. Imagine that Vasily is our salesman. The figure shows that its performance is higher than that of Peter. (I do not presume to say now that this is the case in reality, this is only a model.) Do you think, colleagues, can Vasily divert the incoming customer flow "to the reserve"? No, he can not! A client is a very rapidly deteriorating piece, the passage of which, even within a few minutes, may make it unsuitable for further use.

Now that we have dealt with the streaming systems and some laws in force on them, I am ready to explain my remark in the first chapter about efficiency and loading at 100%. If you force Vasily, Peter and Nicholas to work at full capacity, we will achieve an increase in the number of unfinished work, the departure of dissatisfied customers and conflicts between employees, but not an increase in the efficiency of the entire system.

The “all work at 100%” approach is the local optimization, and from the above, one important conclusion can be made:

Local optimization is bad!

I will cite typical problems for “locally optimized” companies explaining why this is bad:

Problem number 1 : Inefficient use of resources. The head of each of the units, seeking to improve the efficiency of their department, invests strength, money and other resources. Salespeople spend forces on attracting new customers with whom there is no one to work, production purchases materials that will be needed very soon, buyers send goods to the company that are “interesting” at a price, but unnecessary in the market, etc.

Problem number 2 : Constant conflicts in the team. I have already described several conflict situations above, and they all have a common nature of occurrence: within the framework of their department, each employee works best (or, at least, not bad), but from the point of view of employees of other departments, he creates problems.

Problem number 3 : Departure from the work plan and the delay of employees at the workplace at the end of the day Inventories of unfinished work need to rake. At the factories, this is due to the fact that at some moment the blanks in the aisle block it completely, and in our work it looks like a manager's plan, which lacks space. And this causes the following problem.

Problem number 4 : Overall decline in work efficiency. An employee who has more tasks than he should be forced to constantly switch between them. Switching between tasks requires additional time. Moreover, time is spent both on immersing directly into the task left before, and on trying to explain to a colleague requiring it, that another problem that is more important for the company is being solved.

Problem number 5 : Cash gaps. This problem should be described in the “Finance” section, but its causes are also found here. Chaotic spending of funds (as tasks are performed, and resources are spent on them) negates the possibility of planning. And there are constantly situations in which tasks that need to be solved in a week have already been paid, and there is nothing to buy materials for today's work.

It should be noted here that there are not only problems number 3 and number 4. As systemic problems, they are also interconnected into the system. Figure 11 shows a fragment of the problem system that haunts us day after day:

Figure 11. A fragment of the company's problems system.

- Lagging behind the plan gives rise to conflicts between employees, because people who can and want to fulfill the plan constantly demand from the “guilty” (from their point of view) to hurry up or drop everything and switch to the “hung” task.

- Constant conflicts reduce the efficiency of labor, as employees spend time on "disassembling" with each other, on smoke breaks after fights, on switching between tasks. And all this time they do not work.

- Reducing the efficiency of labor leads to a backlog of the plan.

- The backlog from the plan makes it unwise to spend money. If a task consists of several subtasks, and one of them is lagging behind the plan, then in order to “optimize” time, materials are often purchased in advance, which will be needed much later, and services that are needed for subsequent tasks are paid for. Within the framework of one department, this seems to be quite justified step.

- Unreasonable consumption of resources leads to a shortage of working capital. The amount of money on hand is limited. And funds are brought to the cashier, relying on the planned expenditure and planned income. If, in order to save time, money is spent earlier than planned, it is very likely we will remain without funds for current expenses.

- Lack of working capital creates new conflicts. If there is no money in the cashier, the employee cannot purchase materials to complete his task. So, he will not have time to fulfill it in time (7). Therefore, there will be problems again. Again, you will have to work overtime, and over your head constantly someone will complain, demand hurry. So not only is hellish working conditions, so there is no advance payment either.

In order not to make me sad, I brought only a part of the network of problems. If you do not believe, answer the question: “How does the systematic non-fulfillment of plans for relations with clients affect?” Or “How does labor efficiency affect the salaries of employees?”

Effective managers in this place should say: “So let's list all the problems and solve them!” An excellent proposal, but, unfortunately, completely useless. Solving each of these problems separately and even in small groups is nothing but another local optimization.

UPD`17:

I still can not get together to republish the material. If someone really needs or just wondering, here is a link to the original. Please only one: when used in full or in part, indicate the link to the author. All coordinates are in profile .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/145170/

All Articles