How and why to measure FLOPS

As you know , FLOPS is a measure of the computing power of computers in (

As you know , FLOPS is a measure of the computing power of computers in ( Let's first deal with the terms and definitions a bit. So, FLOPS is the number of computational operations or instructions performed on floating-point operands (FP) per second. Here the word “computational” is used, since the microprocessor is able to perform other instructions with such operands, for example, loading from memory. Such operations do not carry the computational load and therefore are not taken into account.

The value of FLOPS published for a specific system is a characteristic primarily of the computer itself, and not of the program. It can be obtained in two ways - theoretical and practical. Theoretically, we know how many microprocessors are in the system and how many executable floating point devices are in each processor. All of them can work simultaneously and begin work on the next instruction in the pipeline each cycle. Therefore, to calculate the theoretical maximum for this system, we only need to multiply all these quantities with the processor frequency — we obtain the number of FP operations per second. Everything is simple, but such assessments are used, except that stating in the press about future plans for building a supercomputer.

')

The practical dimension is to launch the Linpack benchmark. The benchmark performs the operation of multiplying the matrix by the matrix several dozen times and calculates the average value of the test execution time. Since the number of FP operations in the implementation of the algorithm is known in advance, dividing one value by another, we obtain the desired FLOPS. The Intel MKL Library (Math Kernel Library) contains the LAPAC package, a library package for solving linear algebra problems. The benchmark is based on this package. It is believed that its efficiency is at the level of 90% of the theoretically possible, which allows the benchmark to be considered a “reference measurement”. Separately, Intel Optimized LINPACK Benchmark for Windows, Linux and MacOS can be downloaded here , or taken in the composerxe / mkl / benchmarks directory if you have installed Intel Parallel Studio XE.

Obviously, developers of high-performance applications would like to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of their algorithms using the FLOPS indicator, but already measured for its application. A comparison of the measured FLOPS with the “reference” gives an idea of how far the performance of their algorithm is from ideal and what the theoretical potential of its improvement is. To do this, you just need to know the minimum number of FP operations required to perform the algorithm, and accurately measure the program execution time (or part of it that performs the evaluated algorithm). Such results, along with measurements of memory bus characteristics, are needed to understand where the implementation of the algorithm rests on the capabilities of the hardware system and what is the limiting factor: memory bandwidth, data transfer delays, performance of the algorithm, or the system.

Well, now let's dig into the details, in which, as you know, all evil. We have three estimates / measurements of FLOPS: theoretical, benchmark and program. Consider the features of FLOPS calculation for each case.

Theoretical FLOPS rating for the system

To understand how the number of simultaneous operations in a processor is calculated, let's take a look at the out-of-order block device in the Intel Sandy Bridge processor pipeline.

Here we have 6 ports to computing devices, while in one cycle (or processor clock) the dispatcher can be assigned to perform up to 6 micro-operations: 3 memory operations and 3 computing ones. One multiplication operation ( MUL ) and one addition ( ADD ) can be performed simultaneously, both in x87 FP blocks and in SSE or AVX . Given the width of SIMD registers of 256 bits, we can get the following results:

8 MUL (32-bit) and 8 ADD (32-bit): 16 SP FLOP / cycle , that is, 16 single-precision floating-point operations per clock cycle.

4 MUL (64-bit) and 4 ADD (64-bit): 8 DP FLOP / cycle , i.e. 8 double-precision floating point operations per clock cycle.

The theoretical peak value of FLOPS for a 1-socket Xeon E3-1275 (4 cores @ 3.574GHz) available to me is:

16 (FLOP / cycle) * 4 * 3.574 (Gcycles / sec) = 228 GFLOPS SP

8 (FLOP / cycle) * 4 * 3.574 (Gcycles / sec) = 114 GFLOPS DP

Running Linpack benchmark

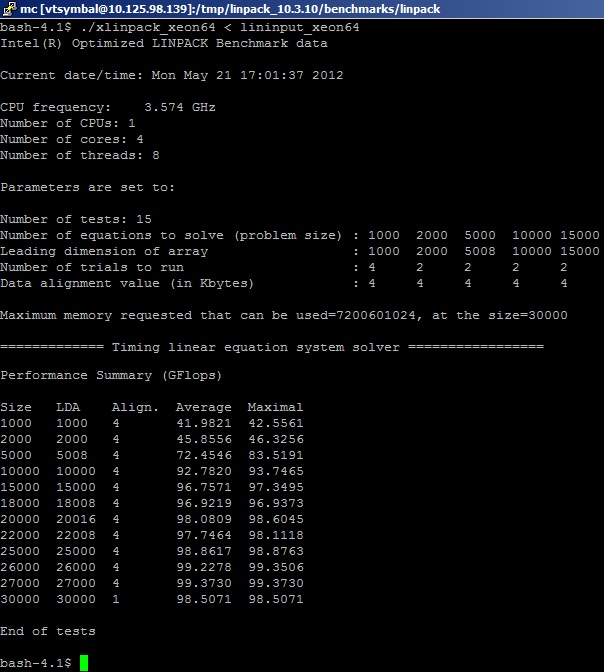

We run the benchmark from the Intel MKL package on the system and get the following results (cut for ease of viewing):

Here you need to say exactly how the FP operations in the benchmark are taken into account. As already mentioned, the test “knows” in advance the number of MUL and ADD operations that are necessary for matrix multiplication. In a simplified representation: the system of linear equations Ax = b (several thousand pieces) is solved by multiplying the dense matrices of real numbers (real8) of size MxK, and the number of addition and multiplication operations necessary for the implementation of the algorithm is considered (for a symmetric matrix) Nflop = 2 * (M ^ 3) + (M ^ 2). Calculations are made for double-precision numbers, as for most benchmarks. How many floating-point operations are actually performed in the implementation of the algorithm, users do not care, although they guess that it is more. This is due to the fact that the decomposition of matrices in blocks and transformation (factorization) are performed in order to achieve the maximum performance of the algorithm on the computing platform. That is, we need to remember that, in fact, the value of physical FLOPS is underestimated due to not taking into account unnecessary conversion operations and auxiliary operations such as shifts.

Evaluation of the FLOPS program

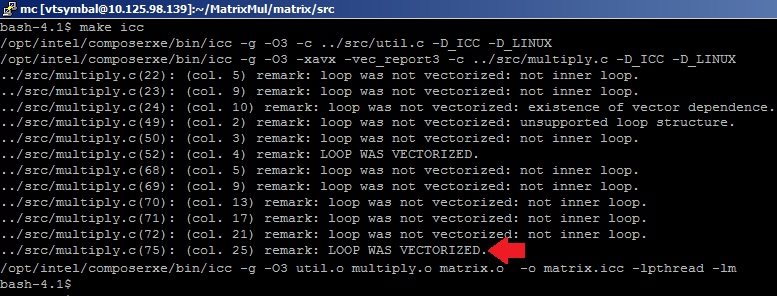

To explore comparable results, as our high-performance application, we will use the do-it-yourself matrix multiplication example, that is, without the help of mathematical gurus from the MKL Performance Library development team. An example of implementation of matrix multiplication written in C can be found in the Samples directory of the Intel VTune Amplifier XE package. We use the formula Nflop = 2 * (M ^ 3) to calculate FP operations (based on the basic matrix multiplication algorithm) and measure the multiplication time for the case of the multiply3 algorithm with the size of symmetric matrices M = 4096. In order to get effective code, we use the optimization options –O3 (aggressive loop optimization) and –xavx (use AVX instructions) of the Intel C compiler to generate vector SIMD instructions for AVX execution devices. The compiler will help us to find out if the matrix multiplication cycle has been vectorized. To do this, specify the option –vec-report3 . In the compilation results we see the optimizer messages: “LOOP WAS VECTORIZED” opposite the line with the body of the internal loop in the file multiply.c .

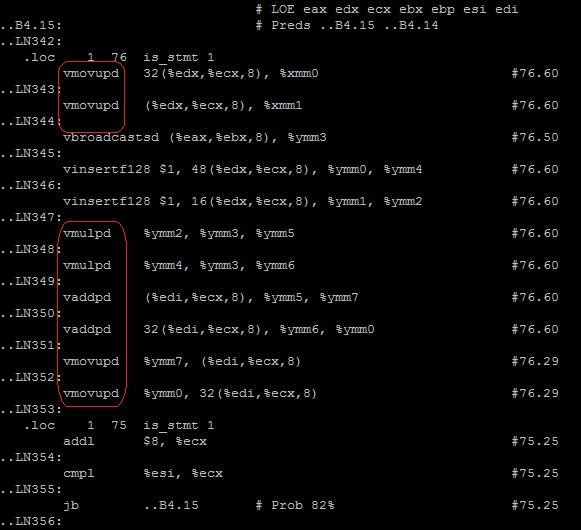

Just in case, we will check what instructions are generated by the compiler for the multiplication cycle.

$ icl –g –O3 –xavx –S

According to the tag __tag_value_multiply3 we are looking for the necessary cycle - the instructions are correct.

$ vi muliply3.s

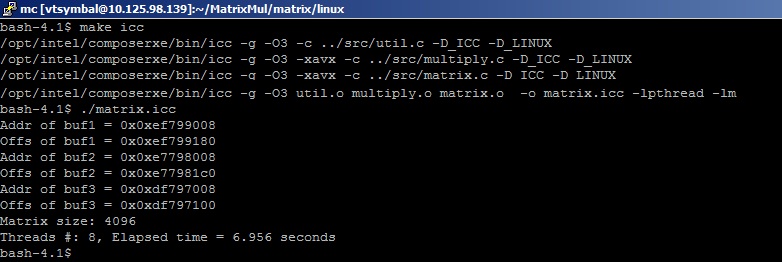

The result of the program (~ 7 seconds)

gives us the following value FLOPS = 2 * 4096 * 4096 * 4096/7 [s] = 19.6 GFLOPS

The result, of course, is very far from what happens in Linpack, which is explained solely by the qualifying chasm between the author of the article and the developers of the MKL library.

Well, now dessert! Actually, for the sake of which I started my research on this seemingly boring and long-beaten topic. New FLOPS measurement method.

Measurement of FLOPS program

There are problems in linear algebra, the program implementation of the solution of which is very difficult to estimate in the number of FP operations, in the sense that finding such an estimate is itself a nontrivial mathematical problem. And here we are, as they say, arrived. How to read FLOPS for a program? There are two ways, both experimental: difficult, giving accurate results, and easy, but providing a rough estimate. In the first case, we will have to take some basic software implementation of the solution to the problem, compile it into assembler instructions and, after executing them on the processor simulator, count the number of FP operations. It sounds so hard that you want to go easy, but unreliable way. Moreover, if the branch of the execution of the task will depend on the input data, then all the accuracy of the assessment will immediately be put into question.

The idea of the easy way is as follows. Why not ask the processor itself how much it performed the FP instructions. Processor pipeline, of course, does not know about it. But we have performance counters (PMU - it ’s interesting here) that can count how many micro-operations were performed on a given computing unit. VTune Amplifier XE can work with such counters.

Despite the fact that VTune has many built-in profiles, it does not yet have a special profile for measuring FLOPS. But no one bothers us to create our own user profile in 30 seconds. Without bothering you with the basics of working with the VTune interface (you can learn them in the Getting Started Tutorial attached to it), I will immediately describe the process of creating a profile and collecting data.

- We create a new project and specify our application matrix as a target application.

- Select the Lightweight Hotspots profile (which uses the Hadware Event-based Sampling processor counter sampling technology) and copy it to create a custom profile. Call him My FLOPS Analysis.

- Edit the profile, add there new processor event counters for the Sandy Bridge processor (Events). We’ll dwell on them a bit more. In their names, executive devices are encrypted (x87, SSE, AVX) and the type of data on which the operation was performed. Each processor clock counters add up the number of computational operations assigned to execution. Just in case, we added counters for all possible operations with FP:

- FP_COMP_OPS_EXE. SSE_PACKED_DOUBLE - vectors (PACKED) of double precision data (DOUBLE)

- FP_COMP_OPS_EXE. SSE_PACKED_SINGLE - single precision data vectors

- FP_COMP_OPS_EXE. SSE_SCALAR_DOUBLE - scalar DP

- FP_COMP_OPS_EXE. SSE_ SCALAR _SINGLE - scalar SP

- SIMD_FP_256.PACKED_DOUBLE - AVX data vectors DP

- SIMD_FP_256.PACKED_SINGLE - AVX data vectors SP

- FP_COMP_OPS_EXE.x87 - x87 scalar data

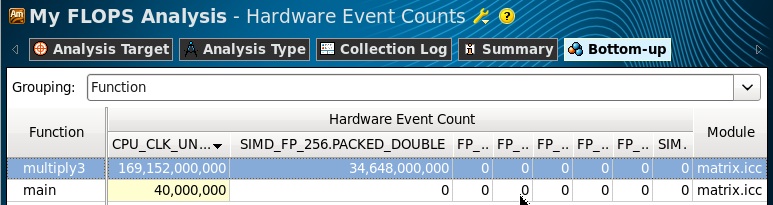

We can only run the analysis and wait for the results. In the obtained results we switch to the Hardware Events viewpoint and copy the number of events collected for the multiply3 function: 34,648,000,000.

Next, we simply calculate the FLOPS values using formulas. We have collected data for all processors, so multiplying by their number is not required here. Double precision operations are performed simultaneously on four 64-bit DP operands in a 256-bit register, so we multiply by a factor of 4. Data with a single precision, respectively, are multiplied by 8. In the last formula, we do not multiply the number of instructions by a factor, since the coprocessor operations x87 are executed with scalar values only. If the program performs several different types of FP operations, their number multiplied by the coefficients is summed to obtain the resultant FLOPS.

FLOPS = 4 * SIMD_FP_256.PACKED_DOUBLE / Elapsed Time

FLOPS = 8 * SIMD_FP_256.PACKED_SINGLE / Elapsed Time

FLOPS = (FP_COMP_OPS_EXE.x87) / Elapsed Time

In our program, only AVX instructions were executed, so the results have the value of only one SIMD_FP_256.PACKED_DOUBLE counter.

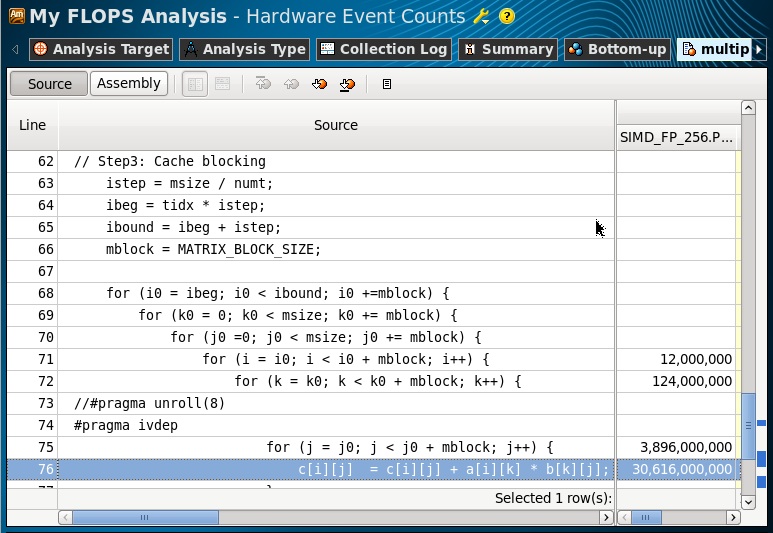

Make sure that event data is collected for our cycle in the multiply3 function (by switching to Source View):

FLOPS = 4 * 34.6Gops / 7s = 19.7 GFlops

The value is consistent with the estimated calculated in the previous paragraph. Therefore, with sufficient accuracy, we can say that the results of the evaluation method and the measurement coincide. However, there are cases where they may not coincide. With a certain interest of readers, I can do their research and tell how to use more complex and accurate methods. And in return, I really want to hear about your cases when you need to measure FLOPS in programs.

Conclusion

FLOPS is a measure of the performance of computing systems, which characterizes the maximum computing power of the system itself for floating-point operations. FLOPS can be claimed as theoretical, for systems that are not yet existing, or measured using benchmarks. Developers of high-performance programs, in particular, solvers of systems of linear differential equations, evaluate the performance of their algorithms, including the value of the FLOPS program, calculated using the theoretically / empirically known number of FP operations needed to run the algorithm and the measured test run time. For cases where the complexity of the algorithm does not allow to estimate the number of FP operations of the algorithm, they can be measured using performance counters built into Intel microprocessors.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/144388/

All Articles