Media Piracy in Developing Economies

An extensive report on piracy in Russia, Brazil, India, South Africa, Mexico and Bolivia was prepared by the Council for Research in the Social Sciences - an authoritative international non-profit organization. This report is the result of three years of work by thirty-five researchers from different countries. It contains more than four hundred pages and is available for free download, including in Russian. This extremely interesting document was mentioned only briefly on Habré, and then the Russian translation did not exist yet. For the text of this volume is a very significant factor.

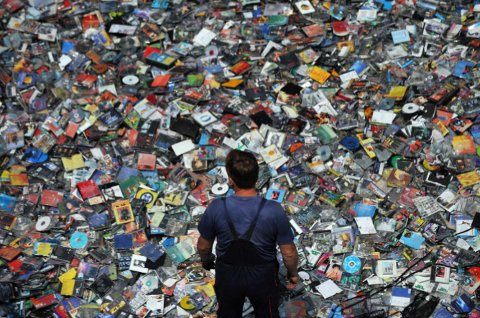

An extensive report on piracy in Russia, Brazil, India, South Africa, Mexico and Bolivia was prepared by the Council for Research in the Social Sciences - an authoritative international non-profit organization. This report is the result of three years of work by thirty-five researchers from different countries. It contains more than four hundred pages and is available for free download, including in Russian. This extremely interesting document was mentioned only briefly on Habré, and then the Russian translation did not exist yet. For the text of this volume is a very significant factor.The two main “storylines” that pass through the entire report are, on the one hand, the explosive growth of piracy due to the availability and cheapness of digital technologies and the Internet, and, on the other hand, changing laws and prosecuting pirates under pressure from the copyright industry lobby. It follows from the report that attempts to combat piracy by prohibitions turned out to be practically unsuccessful, and that the problem of piracy, in the first place, is the problem of accessibility of content on legal trading platforms.

Key findings of the report

Prices are too high. High prices, low income and low cost digital technologies are the main engines of piracy. Regarding the level of income in Russia, South Africa or Brazil, a CD, DVD or copy of MS Office in these countries are five to ten times more expensive than in the US or Europe. Accordingly, the legal trading platforms here are in a barely alive state.

')

Competition is good. To lower prices in the legal market, you need the presence of strong local players. In developing countries, global media corporations dominate the market, preventing the emergence of strong competitors.

Anti-piracy propaganda has failed. In all the countries studied, piracy is not considered shameful and is practiced daily by a significant part of the population.

Change the law is easy. Changing habits is difficult. The rightholders achieved great success by lobbying for changes in legislation criminalizing piracy. However, they failed to enforce these laws. Law-enforcement systems of developing countries easily compensate for the severity of laws by the actual non-binding nature of laws.

Criminals aren't sweet either. Research has not revealed any systematic link between piracy and organized crime or terrorism. As well as “white” intellectual property dealers, criminals who try to make money on counterfeit products are not able to compete with free downloads.

Coercion doesn't work. Ten years of hands-free anti-piracy did not affect the volume and availability of pirated content.

The translation of this remarkable document was made by teachers and students of the Department of Intellectual Property Economics at MIPT (they also participated in the preparation of the report), for which we thank all of them. Here are excerpts from the preface of the translation editor, Doctor of Economic Sciences Anatoly Kozyrev:

... We considered that acquaintance with this material would be very useful for our politicians, rightholders, law enforcement officers, judges, and just citizens wishing to have an adequate understanding of the economics of copyright, freedom on the Internet, and media piracy.

We consciously use the term “media”, which is much broader than the media, since media is also games, software, music, etc. Similarly, the term “content” cannot be replaced by the word “content”; here it means everything that can be digitized in principle.

... It should also be noted that the final report of Media Piracy in Emerging Economies included only a relatively small part of the material collected and analyzed by us. Work in the project together with our foreign partners has expanded our understanding of the subject and showed that further research on the topic is interesting, necessary and, very importantly, fully within our reach. It will certainly continue.

Download the report in PDF format here.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/142248/

All Articles