How Intel's Random Number Generator Works

Imagine that it is 1995 now and you are going to make your first purchase online. You open the Netscape browser and sip from a cup of coffee while the main page loads slowly. Your path lies on Amazon.com - a new online store that a friend told you about. When it comes to the process of making a purchase and entering personal data, the address in the browser changes from “http” to “https”. This signals that the computer has established an encrypted connection to the Amazon server. Now you can transfer credit card data to the server without fear of scammers who want to intercept information.

Unfortunately, your first purchase on the Internet was compromised from the very beginning: it will soon be discovered that the supposedly secure protocol by which the browser established the connection is actually not very secure.

The problem is that the secret keys Netscape used were not random enough. Their length was only 40 bits, which means about a trillion possible combinations. This seems like a large number, but hackers managed to crack these codes, even on computers of the 1990s, in about 30 hours. Allegedly, the random number that Netscape used to generate the secret key was based on only three values: the time of day, the process identification number and the identification number of the mother process — all of them are predictable. Because of this, the attacker had the opportunity to reduce the number of options for busting and find the right key much earlier than Netscape had assumed.

')

Netscape programmers would gladly use completely random numbers to generate the key, but did not know how to get them. The reason is that digital computers are always in a precisely defined state, which changes only when a certain command is received from a program. The best thing you can do is emulate randomness, generating so-called pseudo-random numbers using a special mathematical function. At first glance, the set of such numbers looks completely random, but someone else can easily generate exactly the same numbers using the same procedure, so usually they are poorly suited for encryption.

Researchers managed to invent pseudo-random number generators that are recognized as cryptographically reliable. But they need to be run from a qualitative random seed value, otherwise they will always generate the same set of numbers. And for this initial value, you need something that is really impossible to pick up or predict.

Fortunately, it’s easy to get really unpredictable values using the chaotic universe that surrounds the strictly deterministic world of computer bits on all sides. But how exactly do this?

In recent years, a random number source called Lavarand has been online . It was created in 1996 to automatically generate random values by processing photographs of a decorative luminaire - a lava lamp, which in an unpredictable way changes the appearance every second. Since then, random values from this source have been used more than a million times.

In recent years, a random number source called Lavarand has been online . It was created in 1996 to automatically generate random values by processing photographs of a decorative luminaire - a lava lamp, which in an unpredictable way changes the appearance every second. Since then, random values from this source have been used more than a million times.There are more sophisticated hardware random-number generators that register quantum effects, such as photon strikes in a mirror. You can get random numbers on the most ordinary computer by registering unpredictable events, such as the exact time you press the buttons on the keyboard. But to get a large number of such random values, you have to press a lot of buttons.

My colleagues at Intel decided that an easier way was needed. That is why for more than ten years many of our chipsets contain an analog hardware random number generator. The problem is that its analog circuit wastes energy. In addition, it is difficult to maintain the performance of this analog circuit as the technical process for the production of microcircuits and their miniaturization improves. Therefore, we have now developed a new and fully digital system that allows the microprocessor to generate an abundant stream of random values without these problems. Soon this new digital random number generator will come to you with the new processor.

Intel's first attempt to make the best random number generator on ordinary PCs dates back to 1999, when Intel introduced the Firmware Hub component for chipsets. The random number generator in this chip (PDF) is an analog design based on a ring oscillator that captures thermal noise from resistors, amplifies it, and uses the resulting signal to change the period of a relatively slow clock generator. For each unpredictable “tick” of this slow oscillator, the microcircuit superimposed the oscillation frequency of the second, fast oscillator, which regularly changes its value between two binary states: 0 and 1. The result is an unpredictable sequence of zeros and ones.

The problem is that the ring oscillator, which is engaged in amplification of the heat signal, consumes too much energy - and it works constantly, regardless of whether the computer needs random numbers or not at the moment. These analog components also cause inconvenience every time a company changes its chip production process. Every few years, the company upgrades its production lines to make microchips on a smaller scale. And each time this analog fragment needs to be re-calibrated and tested - this difficult and painstaking work has become a real headache.

That's why in 2008, Intel began developing a random number generator that works exclusively on a digital basis. Researchers at the company in Hillsboro (Oregon, USA), together with Design Lab engineers in Bangalore (India), began to study the key problem - how to get a random bit stream without using analog circuits.

Funny, but the solution they suggest violates the basic rule of digital design, that the scheme should always be in a certain position and return either a logical 0 or 1. Of course, a digital element can spend short periods of time in an undefined position, switching between these two values. However, it must work extremely clearly and never oscillate between them, otherwise it will cause delays or even a system failure. In our random bit generator, the oscillations are features, not a bug .

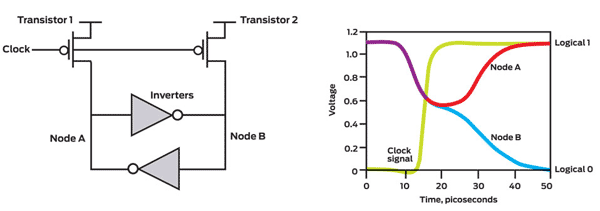

UNCERTAIN DIAGRAMS: When transistor 1 and transistor 2 are turned on, a pair of inverters rotate Node A and Node B to the same position [left]. If the clock frequency increases [the yellow graph on the right], these transistors are turned off. Initially, both inverters turn into an uncertain position, but random thermal noise in the inverters soon turns one node to logical position 1, and the other node to logical position 0.

The design consists of a pair of inverters - circuit elements, in which the value at the output is the inverse of the value at the input. We connected the output of one inverter to the input of another inverter. If the output of the first inverter is 0, then the second inverter receives it at the input and, accordingly, outputs 1. Or if the first inverter issues 1, then the second inverter will output 0.

Additionally, two transistors with a rather strange location were added to the two inverters in the circuit. Turning on these transistors gives a logical 1 input and output for both inverters. Of course, the inverters had to be slightly modified to make such a focus possible, but it is quite simple to do.

The most interesting thing starts when the transistors turn off. Two inverters do not like the fact that they have the same state at the outputs, and they strive to assume the opposite position, that is, one of two stable states. But which inverter will change to 0? It is unknown.

There are two probabilities, and the chain chooses between them. In an ideal world, the status quo can last forever, but in reality even the minimal impact of thermal noise — random atomic vibrations — pushes the circuit into one of two possible stable states.

In this case, our simple digital scheme easily gets a piece of the omnipresent randomness of nature. All we have to do is connect a clock generator, which will regularly turn on and off the transistors. One random bit is generated per clock.

This digital approach to random bit generation would work well if the inverters were exactly the same. But because of the imperfection of the physical world, this never happens. In reality, two inverters are never exactly the same. Differences in their characteristics may seem extremely small, but in this application these differences can easily compromise the random bit stream that we are trying to extract from the circuit.

In order to maintain the balance of the inverters, we have built in a feedback mechanism so that the scheme complies with one of the rules of statistical randomness, according to which in the long sequence there should be the same number of all possible numbers. Thus, we can fight the predictability that inspires such a horror to any cryptologist.

Along with developing a robust digital source of random numbers, other Intel engineers began developing additional logic elements to efficiently process and use these bits. You might think that the processor is able to simply receive a raw bit stream from the generating circuit and insert them into the program. But in fact, these bits are not as random as we would like. Raw flow from the circuit, regardless of the quality of the equipment, in any case may have some distortions in one direction or another.

Our goal was to create a system that generates a stream of random numbers that meets recognized cryptographic criteria, such as the standards of the National Institute of Standards and Technology . To ensure the quality of our random numbers, we developed a three-step process involving the original digital circuit, the “conditioner” (conditioner) and the pseudo-random number generator — now known by the code name Bull Mountain .

Our previous analog generator was able to give out only a couple of hundred kilobits of random numbers per second, while the new one generates them with a stream of about 3 Gb / s. It starts work, collecting almost random values of two inverters in blocks of 512 bits. In the future, these blocks are divided into pairs of 256-bit numbers. Of course, if the original 512 bits are not completely random, these 256-bit numbers will not be completely random either. But they can be mathematically combined in such a way as to get a 256-bit number that is close to ideal.

THREE LEVELS OF NUMBERS: Intel Bull Mountain random number generator prevents any predictability from a three-step process. First, the digital loop generates a stream of random bits. Then the “normalizer” (conditioner) generates good random random values based on this stream. In the third stage, the pseudo-random number generator produces a stream of numbers for use in software.

All this is better shown in a simple illustration. Suppose for a second that the random-bit generator produces 8-bit combinations, that is, like numbers in the range from 0 to 255. Also assume that these 8-bit numbers are not completely random. Now imagine that, for example, some elusive flaw in the circuit shifts the values to the bottom of the range. At first glance, the flow of random numbers seems to be good, but if you process millions of values, you will notice that the numbers from the upper part of the range are less common than the numbers from the lower part.

One of the possible solutions to this problem is simple: always take a pair of 8-bit numbers, multiply them, and then discard the top eight bits from the resulting 16-bit number. This procedure will eliminate the distortion almost entirely.

Bull Mountain does not work with 8-bit numbers: it works, as already mentioned, with 256-bit numbers. And he does not multiply them, but produces more complex cryptographic operations. But the basic idea is the same. You can present this stage as “normalization” to eliminate those deviations from the random distribution of numbers that may occur in a circuit with two inverters.

We really want to sleep well at night, so we have designed an additional circuit that tests the streams of 256-bit numbers that go to the “normalizer” so that they are not too biased in any direction. If this is found, we mark it as defective and not conforming to standards. Thus, operations are performed only with quality pairs of numbers.

Guaranteed randomness is not enough if random values are not issued fast enough to meet the standards. Although the hardware circuit generates a stream much faster than its predecessors, this is still not enough for some modern tasks. So that Bull Mountain could produce random numbers as fast as the program generators of pseudo-random numbers give out, but at the same time maintaining the high quality of random numbers, we added another level to the circuit. Here, 256-bit random numbers are used as cryptographically reliable initial values (random seeds) to generate a large number of pseudo-random 128-bit numbers. Since the 256-bit numbers come with a frequency of 3 GHz, a sufficient amount of material is guaranteed for the rapid generation of cryptographic keys.

The new instruction called RdRand allows the program, which needs random numbers, to request the hardware that produces them. Built for 64-bit Intel processors, the RdRand instruction is the key to the Bull Mountain generator. It extracts 16-, 32-, or 64-bit random values and places them in a register accessible to the program. The RdRand manual was open to the public about a year ago, and the first Intel processor to support it will be the Ivy Bridge. The new chipset works 37% faster than its predecessor, and the size of its minimum elements is reduced from 32 to 22 nanometers. The overall performance increase fits well with the needs of our random number generator.

Although lava lamps look cool , they won't fit into every interior. We think that our approach to generating random numbers, by contrast, will find the most universal application.

As already mentioned, the registration of exact keystrokes was used as a convenient source of random starting values for generators in the past. For the same purpose, using the mouse movement and even the speed of the search sectors on the hard disk. But such events do not always give you a sufficient number of random bits, and with a certain measurement time, these bits become predictable. Worse, since we now live in the server world with SSD and virtualization, these physical sources of accidents are simply not available on many computers. On these machines it is required to get random numbers in some other way, and not by events on peripheral devices. Bull Mountain offers a solution.

So if you are a programmer, be prepared for the appearance of a rich source of randomness right at your fingertips. And even if you do not want to give up your favorite pseudo-random number generator, which you are used to using for cryptography, scientific computing, or even in games - you now have Bull Mountain to get initial values for it. We expect that the use of Bull Mountain will be very popular, with the result that different types of great software will grow and flourish.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/128666/

All Articles