Why do lithium-ion batteries die so early?

Battery Death: We've all seen how this happens. In phones, laptops, cameras, and now electric vehicles, the process is painful and, if lucky, slow. Over the years, the lithium-ion battery that once powered your devices for several hours (and even days!) Gradually loses its ability to hold a charge. In the end, you will accept, perhaps, curse Steve Jobs, and then buy a new battery, or even a new gadget.

Battery Death: We've all seen how this happens. In phones, laptops, cameras, and now electric vehicles, the process is painful and, if lucky, slow. Over the years, the lithium-ion battery that once powered your devices for several hours (and even days!) Gradually loses its ability to hold a charge. In the end, you will accept, perhaps, curse Steve Jobs, and then buy a new battery, or even a new gadget.But why is this happening? What happens in the battery that makes it emit the spirit? The short answer is that, due to the damage caused by prolonged exposure to high temperatures and a large number of charge and discharge cycles, the process of moving lithium ions between the electrodes eventually disrupts.

A more detailed answer, which will lead us through a description of undesirable chemical reactions, corrosion, the threat of high temperatures and other factors affecting performance, begins with an explanation of what happens in lithium-ion batteries when everything works well.

Introduction to Lithium Ion Batteries

In a conventional lithium-ion battery, we find a cathode (or negative electrode) made from lithium oxides, such as lithium oxide with cobalt. We will also find an anode or a positive electrode, which today, as a rule, is made of graphite. A thin, porous separator holds two electrodes apart to prevent short circuits. And an electrolyte made from organic solvents and based on lithium salts, which allows lithium ions to move inside the cell.

In a conventional lithium-ion battery, we find a cathode (or negative electrode) made from lithium oxides, such as lithium oxide with cobalt. We will also find an anode or a positive electrode, which today, as a rule, is made of graphite. A thin, porous separator holds two electrodes apart to prevent short circuits. And an electrolyte made from organic solvents and based on lithium salts, which allows lithium ions to move inside the cell.')

During charging, the electric current moves lithium ions from the cathode to the anode. During discharge (in other words, when using a battery), the ions move back to the cathode.

Daniel Abraham, a scientist at the Argonne National Laboratory, conducting scientific research on the degradation of lithium-ion cells, compared this process with water in a hydropower system. Moving up water requires energy, but it flows down very easily. In fact, it supplies kinetic energy, says Abraham, in a similar way, the lithium-cobalt oxide in the cathode "does not want to give up its lithium." Like water moving upward, energy is needed to move the lithium atoms from the oxide and move them to the anode.

During charging, the ions are placed between the sheets of graphite that make up the anode. But, as Abraham put it, “they do not want to be there, at the first opportunity they will move back,” as water flows down the slope. This is the discharge. A long-lived battery will withstand several thousand such charge-discharge cycles.

When is a dead battery really dead?

When we talk about a “dead” battery, it is important to understand two metrics of performance: energy and power. In some cases, the speed at which you can get energy from the battery is very important. This is power. In electric vehicles, high power makes it possible to quickly accelerate, as well as braking, in which the battery needs to be charged in a few seconds.

When we talk about a “dead” battery, it is important to understand two metrics of performance: energy and power. In some cases, the speed at which you can get energy from the battery is very important. This is power. In electric vehicles, high power makes it possible to quickly accelerate, as well as braking, in which the battery needs to be charged in a few seconds.In cell phones, on the other hand, high power is less important than capacity, or the amount of energy that a battery can hold. High capacity batteries last longer on a single charge.

Over time, the battery degrades in several ways that can affect both capacity and power, until, after all, it simply cannot perform basic functions.

Think about it in another water-related analogy: charging a battery, like filling a bucket with tap water. The volume of the bucket represents the capacity of the battery, or capacity. The speed with which you can fill it - turning the tap to full power or a thin stream is power. But time, high temperatures, multiple cycles and other factors ultimately form a hole in the bucket.

In analogy with a bucket, water seeps. In the battery, lithium ions are removed, or “tethered,” says Abraham. As a result, they lose the ability to move between the electrodes. Therefore, after several months, the mobile phone, which initially required charging once a couple of days, now needs to be charged every day. Then twice a day. In the end, too many lithium ions will “bind” and the battery will not hold any useful charge. The bucket will stop holding water.

What breaks down and why

The active part of the cathode (a source of lithium ions in the battery) is designed with a specific atomic structure to ensure stability and performance. When the ions move to the anode and then return to the cathode, ideally, they would like to return to their original place in order to maintain a stable crystalline structure.

The active part of the cathode (a source of lithium ions in the battery) is designed with a specific atomic structure to ensure stability and performance. When the ions move to the anode and then return to the cathode, ideally, they would like to return to their original place in order to maintain a stable crystalline structure.The problem is that the crystal structure can change with each charge and discharge. Ions from apartment A will not necessarily return home, but may move into apartment B next door. Then the ion from apartment B finds its place occupied by this vagabond and, without entering into confrontation, decides to settle down the corridor. And so on.

Gradually, these "phase transitions" in the substance transform the cathode into a new crystal structure of a crystal with other electrochemical properties. The exact arrangement of atoms, initially providing the necessary performance, varies.

In batteries of hybrid cars, which are only needed to power up when the vehicle accelerates or slows down, Abraham notes, these structural changes occur much more slowly than in electric vehicles. This is due to the fact that in each cycle only a small part of lithium ions moves in the system. As a result, it is easier for them to return to their original positions.

Corrosion problem

Degradation may also occur in other parts of the battery. Each electrode is connected to a current collector, which is essentially a piece of metal (usually copper for the anode, aluminum for the cathode), which collects electrons and moves them to an external circuit. So, we have clay from such an “active” material as lithium-cobalt oxide (which is ceramics and is not a very good conductor), as well as glue-like bonding material deposited on a piece of metal.

Degradation may also occur in other parts of the battery. Each electrode is connected to a current collector, which is essentially a piece of metal (usually copper for the anode, aluminum for the cathode), which collects electrons and moves them to an external circuit. So, we have clay from such an “active” material as lithium-cobalt oxide (which is ceramics and is not a very good conductor), as well as glue-like bonding material deposited on a piece of metal.If the bonding material is destroyed, this leads to a "flaking" of the surface of the current collector. If the metal is corroded, it cannot efficiently move electrons.

Corrosion in the battery may occur as a result of the interaction of the electrolyte and the electrodes. The graphite anode is “lightweight”, i.e. he easily "gives" electrons to the electrolyte. This can lead to undesirable coatings on the surface of graphite. The cathode, meanwhile, is very “oxidizable,” which means that it easily accepts electrons from the electrolyte, which in some cases may corrode aluminum in the current collector or form a coating on parts of the cathode, Abraham says.

Too much good

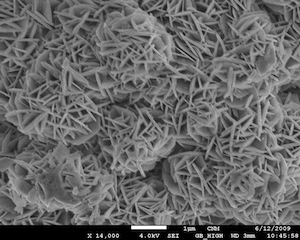

Graphite - a material widely used for the manufacture of anodes - is thermodynamically unstable in organic electrolytes. This means that from the very first charge of our battery, graphite reacts with electrolyte. This creates a porous layer (called a solid electrolyte interface or TEI), which ultimately protects the anode from further attacks. This reaction also consumes a small amount of lithium. In an ideal world, this reaction would occur once, in order to create a protective layer, and that would be the end of it.

Graphite - a material widely used for the manufacture of anodes - is thermodynamically unstable in organic electrolytes. This means that from the very first charge of our battery, graphite reacts with electrolyte. This creates a porous layer (called a solid electrolyte interface or TEI), which ultimately protects the anode from further attacks. This reaction also consumes a small amount of lithium. In an ideal world, this reaction would occur once, in order to create a protective layer, and that would be the end of it.In reality, however, the TEI is a very unstable advocate. It protects graphite well at room temperature, Abraham says, but at high temperatures or when the battery charge drops to zero ("deep discharge"), the TEI can partially dissolve in the electrolyte. At high temperatures, electrolytes also tend to decompose and side reactions are accelerated.

When favorable conditions return, another protective layer will form, but this will eat up some of the lithium, leading to the same problems as the leaky bucket. We will have to charge our cell phone more often.

So, we need a TEC to protect the graphite anode, and in this case, there may really be too much good. If the protective layer is too thick, it becomes a barrier for lithium ions, from which you want to move freely back and forth. This affects power, which, as Abraham stresses, is “extremely important” for electric vehicles.

Creating the best batteries

So what can be done to extend the life of our batteries? Researchers in laboratories are engaged in the search for electrolytic additives that would function like vitamins in our diet, i.e. allowing the battery to work better and live longer by reducing the harmful reactions between the electrodes and the electrolyte, Abraham says. In addition, they are looking for new, more stable crystal structures for electrodes, as well as more stable binding materials and electrolytes.

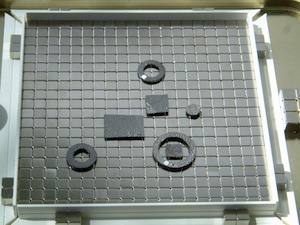

So what can be done to extend the life of our batteries? Researchers in laboratories are engaged in the search for electrolytic additives that would function like vitamins in our diet, i.e. allowing the battery to work better and live longer by reducing the harmful reactions between the electrodes and the electrolyte, Abraham says. In addition, they are looking for new, more stable crystal structures for electrodes, as well as more stable binding materials and electrolytes.Meanwhile, engineers at battery and electric car companies are working on housings and thermal management systems in an attempt to keep lithium-ion batteries in a constant, healthy temperature range. We, as consumers, have to avoid extreme temperatures and deep discharge, and continue to grumble about batteries, which always seem to die too fast.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/123246/

All Articles