Transparent Page Sharing in ESX 4.1 - following the last year’s article

Randomly, a couple of weeks ago, I came across last year’s article by System32 about Transparent Page Sharing , which actually pushed me to break my VCAP-DCA preparation schedule and make a deep dive into the vSphere memory technology completely unknown to me until now accurate - in TPS. A colleague of System32 very sensibly outlined the general principles of working with memory, the algorithm of TPS, but it did not quite correct conclusions. I was even more agitated by questions in comments that no one answered regarding high SHRD memory values on esxtop, despite the fact that according to the same article using Large Pages, TPS technology simply will not work. In general, there were serious contradictions between beautiful theory and practice.

After 4-5 days of digging in the Vmware forums, reading Wiki, Western bloggers , I had something in my head that I could finally answer the questions from the comments. In order to somehow streamline fresh knowledge, I decided to write several articles on this topic in my English-language blog. I also trashed Habr for new articles on this topic, but to my surprise, since 2010 I haven’t found anything new. Therefore, I decided to translate my own article about Transparent Page Sharing and the nuances of its use on systems with Nehalem / Opteron processors and with installed ESX (i) 4.1 for the sake of constantly readable Habr and the opportunity to actively participate in comments.

I do not want to make an article too long, so I highly recommend you (especially if you are a vSphere admin) to first read the article, the link to which I gave at the very beginning. But still, in some trifles, I repeat.

So what is TPS for?

The answer is quite banal - to save RAM, show virtual machines more memory than there is on the host itself, and therefore provide a higher level of consolidation.

')

How does he work?

Historically, in x86 systems, all memory is divided into 4 KB blocks, the so-called pages. When you have 20 virtual machines (VMs) running on the same ESX host with the same OS, you can easily imagine that these VMs have a lot of identical memory pages. To detect duplicate pages on an ESX host, a TPS process is run at intervals of 60 minutes. It scans absolutely all pages in memory and calculates the hash of each page. All hashes are added up to form a single table and checked by the kernel for a match. To avoid the problem called hash collision when finding identical hashes, the kernel checks the corresponding pages bit by bit. And just by making sure that they are 100% identical, the kernel leaves one single copy of the page in memory, and all calls to remote pages are forwarded to that very first copy. If any of the VMs decide to change anything on this page, then ESX will create another copy of the original page and the VM, which sent the change request, will allow working with it. Therefore, in Vmware terminology, this type of page is called Copy-on-write (COW). The process of scanning memory on modern servers with sometimes hundreds of gigabytes of RAM can take a long time, so you should not expect immediate results.

NUMA and TPS

NUMA is a rather curious technology of sharing memory access between processors. Fortunately, the latest versions of ESX are smart enough and know that for efficient NUMA systems, TPS should work only within the NUMA node. In principle, if you correct the value of VMkernel.Boot.sharePerNode in ESX, you can force TPS to compare pages within the entire memory, rather than individual NUMA nodes. It is clear that in this case, you can achieve higher values of SHARED memory, but you need to take into account a possible serious drop in performance. For example, imagine that your ESX host has 4 Xeon 5560 processors, that is, 4 NUMA nodes and each contains an identical copy of the memory page. If TPS leaves one copy in the first node and deletes the other 3, then this means that every time one of the VMs working on these 3 nodes needs the page you are looking for, 3 processors will have to access it not through a local and very fast memory bus. , and through the general and slow. The more pages you have, the less bandwidth remains on the shared bus, and therefore the performance of your virtual machines suffers more.

Zero Pages

One of the great new features introduced in vSphere 4.0 was zero page recognition. In principle, this is a regular page, which is filled with zeros from beginning to end. Each time the Windows VM turns on, all memory is reset to zero, this helps the OS determine the exact amount of available memory. ESX can instantly detect such pages in virtual machines, and instead of the useless process of allocating physical memory to zero pages, and then deleting them during TPS, ESX immediately redirects all such pages to a single zero page. If you run esxtop and check the memory values for the newly started VM, you will find out that the ZERO and SHRD values are almost identical.

However, it is important to note here that this remarkable new feature of ESX 4.0 (and later) can only be used on processors with EPT (Intel) or RVI (AMD) technologies. On this subject there are a couple of excellent articles on the site Kingston ( part one , part two ). In short, it tells and shows how on new processors zero pages are recognized without allocating physical memory to them, and on old processors physical memory is still allocated, and only when TPS has fully worked out does the reduction in physical memory used begin. For ordinary vSphere farms, this is not critical in principle, but for VDI infrastructures, where you can have hundreds of virtual machines starting at the same time, this is extremely useful.

A pair of TPS features with zero pages.

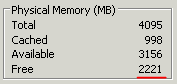

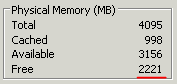

1 . In Windows OS, there is a technology called "file system caching" (I apologize if something where my translation of names and definitions is inaccurate). Using the MS definition, we can say that "File system caching is a region of memory that stores recently used information for quick access." This cache is located in the address space of the kernel, and therefore, in 32bit systems, its size is limited to 1 gigabyte. However, in 64bit systems, its size can reach 1 terabyte ( proof ). In principle, the technology is very useful for performance, but if we have a situation with virtual machines and zero large pages (2 megabytes), then the value of SHRD in esxtop you will tend to zero.

The screenshot above showed the esxtop value immediately after the launch of the Windows 2008 R2 virtual machine, and this is what esxtop showed after half an hour.

Although in the Task Manager of this virtual machine you can easily see how much more free (zero) memory we have.

Unfortunately, I didn’t get to the bottom of why this is how things are going, but it seems to me that file system caching does not occur as a continuous write to memory, but to various areas of it.

2 Zeroing of memory pages in a virtual machine occurs only when it is turned on. With a standard restart, the pages are not reset.

Large pages

The size of large pages used by the kernel in ESX is 2 megabytes. The chances of two identical large pages in physical memory are almost zero, so ESX doesn't even try to compare them. When you use new processors with EPT / RVI, it means that the host will aggressively try to use large pages where possible. If you look at the SHRD value in such hosts, you will be unpleasantly surprised by its low value, but nevertheless it is still a significant quantity. On my production host, with 70 GB allocated, about 4 GB was SHRD. This, by the way, was one of the most interesting questions in the comments of the article, with which my interest in this topic began. Now I know that these are just zero pages, and then I was terribly tormented by ignorance and guesswork.

This low score initially sparked heated discussions in the VMware forums for the simple reason that people decided that TPS stopped working at all in their ESX 4.0 hosts. Vmware was forced to post a clarification on this.

Nevertheless, even when your host is actively using large pages TPS does not sleep at all. He also methodically scans the memory for the same 4 KB pages, which he could use to remove his will. As soon as he finds the same page, he puts a bookmark (hint) there. When the value of the memory used in ESX reaches 94%, your host immediately splits large pages into small pages and without wasting any time on scanning (TPS, after all, already bookmarked) again starts to delete identical pages. If you have not yet reached this point, then in the same esxtop, in the COWH (Copy-on-write hints) field, you can see how much you can save after the big pages are broken into small pages.

Again, I would like to draw attention to the difference in working with large pages between old and new processors. Vmware itself has included support for large pages since version 3.5. In accordance with the document " Large Page Performance " from Vmware, if your virtual machine's OS uses large pages, then the ESX host will allocate large pages in physical memory for this particular VM. However, if the same virtual machine runs on an ESX host with EPT / RVI processors, regardless of the support for large pages of your VM, ESX will use large pages in physical memory, which, as we know from the same document, leads to a serious increase in processor performance.

What is interesting, on a pair of hosts with old processors and ESX 4.1, on which 90% of Windows 2008R2 is spinning, I still see a very high SHRD, which means that small pages are most likely used there. Unfortunately, I did not find detailed documentation on how the support for large pages on older processors works: under what conditions, on what OS, etc., will the large pages be used. So for me it is still a white spot. In the near future I will try to run pieces 10 of Windows 2008 R2 on an ESX 4.1 host with an old processor and check the memory values.

When I only learned it more or less, I was puzzled - and what will happen if I manually disable support for large pages on my host with a Nehalem processor? How much memory will I see and how much will my performance drop? “Well, what can I think about for a long time? I have to do it,” I thought and turned off support for large pages on one of our production hosts. Initially, this host had 70 GB of allocated memory and 4 GB of shared memory (well, yes, we remember - these are zero pages). The average processor load never rose above 25%. Two hours later, after disconnecting large pages, the value of shared memory increased to 32 GB, and the processor load remained at the same level. 4 weeks have passed since then, and we have not heard a single complaint about a drop in performance.

Well, finally my conclusion

After I shared the information with my colleagues, I was asked, “And why not take a steam bath with the support for large pages turned off, if the host already disables them if needed?”. And I immediately knew the answer - with the support for large pages enabled by default, I can’t fully see how much I can potentially save memory with TPS, I can’t correctly plan additional VMs on my ESX hosts, I can’t predict the level of consolidation, in general I’m a little bit blind in terms of managing the resources of his vSphere farm. However, the guru of the vSphere, for example, Duncan Epping, assured that “do not worry, TPS doesn't care when it comes to work, and at the same time you have an excellent performance boost.” After another couple of days, I found a wonderful discussion between him and other authorities of the virtualization world, which only confirmed the correctness of my decision to turn off the large pages. Some say that you can use the value of COWH to plan the use of your resources, but for some reason this value is not always true. This screenshot shows the values of one of my Windows 2003 servers, which has been running for 3 weeks on a host with large pages disabled, and as you can see the values of SHRD and COWH are very different.

A week ago, we turned off large pages on another 4 hosts, another farm, and again I did not notice any drop in performance. Although it is worth noting that this is all individually, and you should take into account the specifics of your farm, resources, virtual machines when making such a decision.

If I'm lucky, and this article seems interesting, I would gladly translate my other article about the difference in memory management between processors of the old and new generation.

After 4-5 days of digging in the Vmware forums, reading Wiki, Western bloggers , I had something in my head that I could finally answer the questions from the comments. In order to somehow streamline fresh knowledge, I decided to write several articles on this topic in my English-language blog. I also trashed Habr for new articles on this topic, but to my surprise, since 2010 I haven’t found anything new. Therefore, I decided to translate my own article about Transparent Page Sharing and the nuances of its use on systems with Nehalem / Opteron processors and with installed ESX (i) 4.1 for the sake of constantly readable Habr and the opportunity to actively participate in comments.

I do not want to make an article too long, so I highly recommend you (especially if you are a vSphere admin) to first read the article, the link to which I gave at the very beginning. But still, in some trifles, I repeat.

So what is TPS for?

The answer is quite banal - to save RAM, show virtual machines more memory than there is on the host itself, and therefore provide a higher level of consolidation.

')

How does he work?

Historically, in x86 systems, all memory is divided into 4 KB blocks, the so-called pages. When you have 20 virtual machines (VMs) running on the same ESX host with the same OS, you can easily imagine that these VMs have a lot of identical memory pages. To detect duplicate pages on an ESX host, a TPS process is run at intervals of 60 minutes. It scans absolutely all pages in memory and calculates the hash of each page. All hashes are added up to form a single table and checked by the kernel for a match. To avoid the problem called hash collision when finding identical hashes, the kernel checks the corresponding pages bit by bit. And just by making sure that they are 100% identical, the kernel leaves one single copy of the page in memory, and all calls to remote pages are forwarded to that very first copy. If any of the VMs decide to change anything on this page, then ESX will create another copy of the original page and the VM, which sent the change request, will allow working with it. Therefore, in Vmware terminology, this type of page is called Copy-on-write (COW). The process of scanning memory on modern servers with sometimes hundreds of gigabytes of RAM can take a long time, so you should not expect immediate results.

NUMA and TPS

NUMA is a rather curious technology of sharing memory access between processors. Fortunately, the latest versions of ESX are smart enough and know that for efficient NUMA systems, TPS should work only within the NUMA node. In principle, if you correct the value of VMkernel.Boot.sharePerNode in ESX, you can force TPS to compare pages within the entire memory, rather than individual NUMA nodes. It is clear that in this case, you can achieve higher values of SHARED memory, but you need to take into account a possible serious drop in performance. For example, imagine that your ESX host has 4 Xeon 5560 processors, that is, 4 NUMA nodes and each contains an identical copy of the memory page. If TPS leaves one copy in the first node and deletes the other 3, then this means that every time one of the VMs working on these 3 nodes needs the page you are looking for, 3 processors will have to access it not through a local and very fast memory bus. , and through the general and slow. The more pages you have, the less bandwidth remains on the shared bus, and therefore the performance of your virtual machines suffers more.

Zero Pages

One of the great new features introduced in vSphere 4.0 was zero page recognition. In principle, this is a regular page, which is filled with zeros from beginning to end. Each time the Windows VM turns on, all memory is reset to zero, this helps the OS determine the exact amount of available memory. ESX can instantly detect such pages in virtual machines, and instead of the useless process of allocating physical memory to zero pages, and then deleting them during TPS, ESX immediately redirects all such pages to a single zero page. If you run esxtop and check the memory values for the newly started VM, you will find out that the ZERO and SHRD values are almost identical.

However, it is important to note here that this remarkable new feature of ESX 4.0 (and later) can only be used on processors with EPT (Intel) or RVI (AMD) technologies. On this subject there are a couple of excellent articles on the site Kingston ( part one , part two ). In short, it tells and shows how on new processors zero pages are recognized without allocating physical memory to them, and on old processors physical memory is still allocated, and only when TPS has fully worked out does the reduction in physical memory used begin. For ordinary vSphere farms, this is not critical in principle, but for VDI infrastructures, where you can have hundreds of virtual machines starting at the same time, this is extremely useful.

A pair of TPS features with zero pages.

1 . In Windows OS, there is a technology called "file system caching" (I apologize if something where my translation of names and definitions is inaccurate). Using the MS definition, we can say that "File system caching is a region of memory that stores recently used information for quick access." This cache is located in the address space of the kernel, and therefore, in 32bit systems, its size is limited to 1 gigabyte. However, in 64bit systems, its size can reach 1 terabyte ( proof ). In principle, the technology is very useful for performance, but if we have a situation with virtual machines and zero large pages (2 megabytes), then the value of SHRD in esxtop you will tend to zero.

The screenshot above showed the esxtop value immediately after the launch of the Windows 2008 R2 virtual machine, and this is what esxtop showed after half an hour.

Although in the Task Manager of this virtual machine you can easily see how much more free (zero) memory we have.

Unfortunately, I didn’t get to the bottom of why this is how things are going, but it seems to me that file system caching does not occur as a continuous write to memory, but to various areas of it.

2 Zeroing of memory pages in a virtual machine occurs only when it is turned on. With a standard restart, the pages are not reset.

Large pages

The size of large pages used by the kernel in ESX is 2 megabytes. The chances of two identical large pages in physical memory are almost zero, so ESX doesn't even try to compare them. When you use new processors with EPT / RVI, it means that the host will aggressively try to use large pages where possible. If you look at the SHRD value in such hosts, you will be unpleasantly surprised by its low value, but nevertheless it is still a significant quantity. On my production host, with 70 GB allocated, about 4 GB was SHRD. This, by the way, was one of the most interesting questions in the comments of the article, with which my interest in this topic began. Now I know that these are just zero pages, and then I was terribly tormented by ignorance and guesswork.

This low score initially sparked heated discussions in the VMware forums for the simple reason that people decided that TPS stopped working at all in their ESX 4.0 hosts. Vmware was forced to post a clarification on this.

Nevertheless, even when your host is actively using large pages TPS does not sleep at all. He also methodically scans the memory for the same 4 KB pages, which he could use to remove his will. As soon as he finds the same page, he puts a bookmark (hint) there. When the value of the memory used in ESX reaches 94%, your host immediately splits large pages into small pages and without wasting any time on scanning (TPS, after all, already bookmarked) again starts to delete identical pages. If you have not yet reached this point, then in the same esxtop, in the COWH (Copy-on-write hints) field, you can see how much you can save after the big pages are broken into small pages.

Again, I would like to draw attention to the difference in working with large pages between old and new processors. Vmware itself has included support for large pages since version 3.5. In accordance with the document " Large Page Performance " from Vmware, if your virtual machine's OS uses large pages, then the ESX host will allocate large pages in physical memory for this particular VM. However, if the same virtual machine runs on an ESX host with EPT / RVI processors, regardless of the support for large pages of your VM, ESX will use large pages in physical memory, which, as we know from the same document, leads to a serious increase in processor performance.

What is interesting, on a pair of hosts with old processors and ESX 4.1, on which 90% of Windows 2008R2 is spinning, I still see a very high SHRD, which means that small pages are most likely used there. Unfortunately, I did not find detailed documentation on how the support for large pages on older processors works: under what conditions, on what OS, etc., will the large pages be used. So for me it is still a white spot. In the near future I will try to run pieces 10 of Windows 2008 R2 on an ESX 4.1 host with an old processor and check the memory values.

When I only learned it more or less, I was puzzled - and what will happen if I manually disable support for large pages on my host with a Nehalem processor? How much memory will I see and how much will my performance drop? “Well, what can I think about for a long time? I have to do it,” I thought and turned off support for large pages on one of our production hosts. Initially, this host had 70 GB of allocated memory and 4 GB of shared memory (well, yes, we remember - these are zero pages). The average processor load never rose above 25%. Two hours later, after disconnecting large pages, the value of shared memory increased to 32 GB, and the processor load remained at the same level. 4 weeks have passed since then, and we have not heard a single complaint about a drop in performance.

Well, finally my conclusion

After I shared the information with my colleagues, I was asked, “And why not take a steam bath with the support for large pages turned off, if the host already disables them if needed?”. And I immediately knew the answer - with the support for large pages enabled by default, I can’t fully see how much I can potentially save memory with TPS, I can’t correctly plan additional VMs on my ESX hosts, I can’t predict the level of consolidation, in general I’m a little bit blind in terms of managing the resources of his vSphere farm. However, the guru of the vSphere, for example, Duncan Epping, assured that “do not worry, TPS doesn't care when it comes to work, and at the same time you have an excellent performance boost.” After another couple of days, I found a wonderful discussion between him and other authorities of the virtualization world, which only confirmed the correctness of my decision to turn off the large pages. Some say that you can use the value of COWH to plan the use of your resources, but for some reason this value is not always true. This screenshot shows the values of one of my Windows 2003 servers, which has been running for 3 weeks on a host with large pages disabled, and as you can see the values of SHRD and COWH are very different.

A week ago, we turned off large pages on another 4 hosts, another farm, and again I did not notice any drop in performance. Although it is worth noting that this is all individually, and you should take into account the specifics of your farm, resources, virtual machines when making such a decision.

If I'm lucky, and this article seems interesting, I would gladly translate my other article about the difference in memory management between processors of the old and new generation.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/121993/

All Articles