Bear Ballet and Artificial Intelligence

“A massive, bulky beast clumsily steps from paw to paw. Dancing bear is just awful, but the miracle is not that he dances well, but that he dances at all. ”

Alan Cooper on Interfaces, "Mental Hospital in the Hands of Patients"

The graphical interface and command line are often opposed to each other. And the fact that GUI fans consider merit is, in the eyes of CLI fans, a disadvantage. And vice versa. “GUI is a self-documented interface. - say the first, - I do not need to read the instructions in order to understand a well-designed GUI, I just look at it, open the menu, another, third, and after a few minutes (or seconds) I do what I need. ” “What about the tenth or hundredth time? - objected second. - All this abundance of buttons and icons turns into annoying visual noise and interferes with work. And the speed? How can walking on multi-level menus compare with the swiftness of keyboard commands? ”“ Rapidity, speak? - answer the first, - But to study the manual on hundreds of pages in small print to get out of your Vim, is it also fast? ”

The graphical interface and command line are often opposed to each other. And the fact that GUI fans consider merit is, in the eyes of CLI fans, a disadvantage. And vice versa. “GUI is a self-documented interface. - say the first, - I do not need to read the instructions in order to understand a well-designed GUI, I just look at it, open the menu, another, third, and after a few minutes (or seconds) I do what I need. ” “What about the tenth or hundredth time? - objected second. - All this abundance of buttons and icons turns into annoying visual noise and interferes with work. And the speed? How can walking on multi-level menus compare with the swiftness of keyboard commands? ”“ Rapidity, speak? - answer the first, - But to study the manual on hundreds of pages in small print to get out of your Vim, is it also fast? ”This dispute can be stretched for several paragraphs, but it is better to think about this: is it really necessary to endure the shortcomings of each of the interfaces? Is it possible to quickly harness and just as quickly go? After all, supporters of the GUI really do not like buttons and multi-colored icons, they love the ease of learning. The masterpieces of graphical interface design are always light and concise, you will not find in them a riot of colors and placers of buttons. And command line lovers are not tied to monochrome asceticism, but to the speed, unobtrusiveness and predictability of the console. Just look at the abundance of color schemes for the syntax highlighting of the same Vim to make sure that the harsh console gamers also like to be beautiful.

')

A bear dancing no worse than a ballerina, an interface with large and beautiful graphic tips that do not even have an eye blistering, with a flexible and powerful set of keyboard commands and abbreviations that should not be studied - fiction, and only that. And no. Such interfaces already exist. Only they for some reason occupy a rather narrow niche. But about them a bit later.

Making a normal GUI is an order of magnitude more difficult than a CLI. Moreover, this is not just a more labor-intensive process - it requires completely different knowledge, experience and mentality than are inherent in the programmer. That is why the strange and unusual command line parameters usually cause only slight bewilderment, but some GUIs are capable of white-hot. GUI Requirements are the most expressive example of mutually exclusive paragraphs. Everything should be visible, and accessible at the first click of the mouse - and nothing extra should be seen in the context of the current task. It is necessary to connect the keyboard, and immediately the main advantage of the GUI disappears - ease of development. Try to remember all these Ctrl + Alt + Shift things!

The command line simply cuts this Gordian knot, without even trying to unravel. Usability CLI - almost constant value for any program. It’s almost impossible to make the keyboard commands inexpressibly awful and confusing. But to reach some unprecedented heights, too, will not work.

The key to designing a good interface is code reuse. Not only software, but also genetic. This truth was well understood by the designers of the physical interfaces - they give objects a form compatible with the person. Handles that fit comfortably in the palm, eye-level indicators, pedals with well-adjusted pressing force actively use the “library” developed by us over millions of years of evolution to interact with real-world objects. This makes the interface intuitive.

But our brains are not that simple! In addition to low-level “drivers” of arms, legs, or eyes, we have in our head much more complex programs for communicating with other living beings. And they know nothing about any computers. Since nature has never existed inanimate objects with complex behaviors, our genetic libraries consider computers as living beings. This is a very important fact for interface design. Living organisms are fundamentally different from inanimate objects. They can not have buttons and levers. They do not allow to tune themselves, but they are able to adapt, they take the initiative, they react to emotions.

Imagine the confusion of our subconscious when confronted with a typical modern graphical interface. It is obvious to him that in front of him a living creature - well, it cannot be a stone, a tree or water, it is so difficult to behave and be on your mind. At the same time, this creature absolutely does not respond to attempts to establish emotional contact with it. Moreover, it does not even try to remember the people who communicate with it, to take into account their habits, to guess their intentions. It obviously suffers from autism in the hardest form. After all, the one who wrote this application imagined it in the form of such a box with tools - here we have scissors, a magnifying glass here, a ruler here. And in general - this is just a sequence of instructions in the computer's memory, what kind of living things are there, what are you talking about?

Of course it's true. As well as the fact that each person is just a walking set of organs, music is a combination of acoustic vibrations, and painting is flat surfaces with coloring substances applied to them. Only, I'm afraid, our brain does not agree with this. And we have to reckon with his opinion - we will not wait for the firmware update in the near future (and should we?). Inside each of us, despite the higher technical and ability to use a debugger or a soldering iron, here sits a beast:

Live programs are a very powerful metaphor. Human interaction with the program is communication between two living beings. Each program is a servant, or a subordinate, or a consultant, or at least a lap dog that can bark on command and bring slippers. Living creatures with whom it is pleasant to communicate, behave politely and intelligently. They are moderately independent, they are interested in us - they remember the preferences, adapt to our habits. Eh, how few such programs ... More often they are rude, rude and stupid.

How to make the program's behavior more similar to the behavior of a living being? If we are talking about the GUI, then we need a fair cleaning. Animals and people are not like the dashboard of an airplane. They have only a few “indicators” and “controls” - ears, eyes, hands (paws), facial expressions, posture, gestures, speech. But they are universal and much more informative.

The command line is the opposite. It supports verbal communication (although it is usually some kind of miserable jargon of letters, punctuation marks and word fragments, in the style of Ellochka-cannibals), but there are no visual cues - an analogue of non-verbal communication - no.

Both types of interfaces are equally poorly adapted to a specific person. Teams can not change over time, reducing and adjusting to the most frequent actions - because then they will have to be re-taught. Similarly, the graphical user interface - the form, size and location of elements are set rigidly, fixed. There is, of course, the ability to change settings, but it is absolutely unnatural when communicating with a living creature - it's like opening a person with a scalpel and swapping hands.

So, it’s time to present the promised programs with an interface that combines the incompatible, quiet and inconspicuous, like a command line, easy to learn and cute, like a good GUI, and flexible, like a living being. These are “launchers” - Gnome do under Ubuntu, Launchy under Windows, Quicksilver under Mac OS. I absolutely do not understand why so far such interfaces are not used wherever possible. I'll tell you more about Gnome do, since I communicate with him most often.

This cute little animal sits quietly in memory and waits until I call it with a conditional whistle - win-space. He always appears in the middle of the screen and looks at me with intelligent square eyes, waiting for a command. From the first typed letter, he tries to guess what I want by displaying a list of programs, folders and files whose names contain the entered characters, and in his eyes are reflected icons or miniatures of objects that are at the top of the list. However, he remembers my previous actions. So, when I just staged the Opera, to launch it I had to type “oper”, because in response to “o”, “op” and “ope” he assumed “Open Ofiice Writer”. But he learns fast. And after only a couple of days, he began offering Opera with the first letter. Thanks to his large, expressive eyes, familiar logos are clearly visible, even if you look past the monitor. Now I launch the main applications and open frequently used folders and documents at the speed of thought, without taking my hands off the keyboard. At the same time, unlike the console commands, I rarely have to type more than three - four letters.

Gnome do completely replaces the main menu and application shortcuts, in part - the file manager. To get started, you need to remember exactly one keyboard shortcut. And if you learn to use Tab, then Gnome do can do almost everything.

What prevents to embed the same thing in any complex application with a bunch of functions? Why keep dozens of menus, buttons, and sliders all the time? To look cool? Out of fear that the great features of the program will not be used? Or is it just the power of habit? I dont know…

The situation on the Internet is even worse. Here, the existence of the keyboard is almost forgotten. Perhaps a fair amount of nostalgia for fidoshnikov in the good old days is in fact connected with the text mode. Now any large and mature site contains hundreds of sections, categories and other nooks through which you have to wade through exclusively with your mouse. Only occasionally a caring web designer will adjust some Ctrl-arrows for scrolling through the gallery with pictures. Well, plus the search string on the site (which you still need to aim with the mouse). To achieve the cherished three clicks between any two pages, different levels of the menu are placed on the top, bottom, side, and on the other side, and then sprinkled with bread crumbs, to be sure.

I never managed to find a single site where full navigation without a mouse would have been possible. Switching Tab between several dozens or, more often, hundreds of active elements on a page is a mockery of a person. A “live” site search while dialing through AJAX is a mockery of the server (and quite tangible brakes). In order to at least try how to work with the site through an interface similar to Gnome do, I had to make such an interface myself. Own impressions and reviews of experimental relatives - the most positive. Here is a demo site where you can touch everything live. Very unusual sensations - to move freely around the site without touching the mouse!

Another nice example of a live interface is Aardvark . This is a question and answer service, but unlike ask.com and others, I answer more often than I ask. And all because it does not look like a multi-colored web page with a bunch of links and buttons, but as one of the contacts in google talk. My subconscious does not see the difference between a person in the contact list and the robot. The genetic program supports this interface.

In general, a good interface cannot be seen or heard until it is needed (unlike the GUI), and it understands you half-word (as opposed to the command line). Neither give nor take is the perfect servant.

Creating such an interface is difficult. But this complexity will pay off. People will be easy with him. Now non-verbal interfaces are rapidly developing - multi touch screen, face recognition and gestures. It seems that the command line has no future in mass devices - they often do not have a keyboard either. But, sooner or later, computers will learn to confidently recognize live speech, transforming the flow of phonemes into a stream of characters. But does it really matter where this stream comes from - from the keyboard or speech recognition module? Same command prompt. Yes, and speech, and gestures, and facial expressions after pattern recognition are transformed into symbols or words.

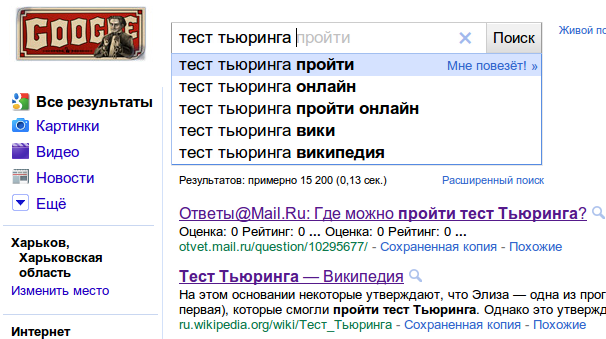

Today's interfaces perceive any signals as commands, like primitive unconditional reflexes. Of course, this provides absolute control, but it severely limits the possibilities. Even the most modest attempts to “guess” the meaning of the incoming signals, at least with the help of a primitive regular expression for a fuzzy search, greatly improve interaction with the program. For example, one of the most convenient and useful features of the IDE and advanced text editors is the ability to instantly go to any project file by typing a few letters of its name (Go to file, Go to resource, FuzzyFinder, etc.) In the same direction goes Google with its live search. Gnome do the same. A person should not adapt to the computer, cram into his commands, get used to his glitches and learn to aim accurately at the small buttons. This computers must adapt to the person, learn his habits and correct his typos. And if they learn to do it well, then maybe Turing tests will click like nuts? However, according to Google, they are already trying with might and main:

UPD: Thanks to the collective mind of Habr - very interesting examples emerged in the comments that implement the adaptive style of working with the command line described in the article in a graphical environment - a plugin for Firefox Ubiquity , a YubNub web service and a dextor launcher-calculator-spellchecker-and-many more Enso

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/116092/

All Articles