What does the Chinese keyboard look like?

You probably imagined it as a whole organ - a grand structure a couple of meters long with hundreds and thousands of keys. In fact, most Chinese use a regular keyboard with a Latin QWERTY layout. But how can you use such an infinite number of different hieroglyphs with it? We asked to tell about this our employee Julia Dreyzis. It is associated with China and old love and work.

For several thousand years, the clever Chinese managed to bring the number of hieroglyphs to 50,000 with a tail. And although the number of characters needed in everyday life is not measured in tens of thousands, it doesn’t matter what you might say, the standard set of the old typography is 9000 letters.

For a long time, the set was carried out according to the principle “for each hieroglyph is a separate printed element”. Therefore, I had to work with monster typewriters like this:

')

Typewriter firm "Shuanghe", 1947 (the principle of operation was invented by the Japanese Kyoto Sugimoto in 1915).

Its main element is a bank of hieroglyphs on an ink pad. Above the hieroglyphs there is a mechanical system: a handle, a “foot” for gripping and a reel with a sheet of paper. The whole mechanism, along with the reel following the handle, is able to move left, right, forward and backward due to the effort of the driver. To type the text, the driver searches for a long time with a magnifying glass for the desired hieroglyph, places the system above it and presses the "foot" on the handle, which grabs the hieroglyph on the fly, unwraps it, stamps it on a piece of paper. At the same time, the sheet reel rotates slightly, providing space for the next character. Of course, the process of printing on such a unit is extremely slow - an experienced operator could recruit no more than 11 characters per minute.

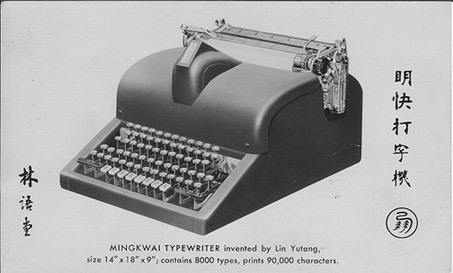

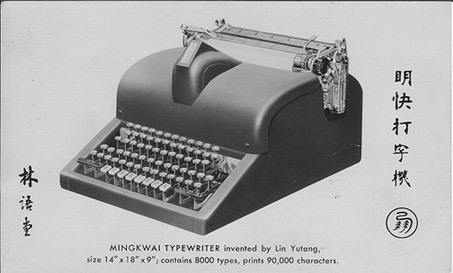

In 1946, the famous Chinese philologist Lin Yutan proposed a version of a typewriter built on a completely new principle - the decomposition of hieroglyphs into its component parts.

Lin Yutang Electromechanical Typewriter, 1946

In contrast to the overall predecessors, the new machine was no more than its Latin counterparts, and the keys on it were few. The fact is that the keys corresponded not to hieroglyphs, but to their component parts. In the center of the device was a "magic eye": when the driver pressed the key combination, a version of the hieroglyph appeared in the "eye". To confirm the choice, it was necessary to press an additional function key. With only 64 keys, such a machine could easily provide a set of 90,000 characters and a speed of 50 characters per minute!

Although Lin Yutang managed to get a patent for his invention in the United States, it never went to the masses. It is not surprising, because the production of one such device at that time cost about 120,000 dollars. Moreover, on the day when the presentation was appointed for the Remington company, the machine refused to work - even the magic eye did not help. The idea was successfully postponed until better times.

But in the era of the wide spread of computers, Lin Yutang's idea of decomposing hieroglyphs into its component parts gained a new life. It formed the basis of the structural input methods for Chinese characters, which we will now discuss.

(By the way, in the 1980s, the Taiwanese company MiTAC even developed, directly on the basis of Lin Yutang’s coding system, its own structural input method, Simplex.)

At least a dozen of such methods are known, and all of them are based on the graphic structure of a hieroglyph. Chinese characters are puzzles assembled from the same parts (the so-called grapheme). The number of these graphemes is not so large - 208, and they can already be “stuffed” into a regular keyboard. True, we get about 8 graphemes per key, but this problem is easily solved.

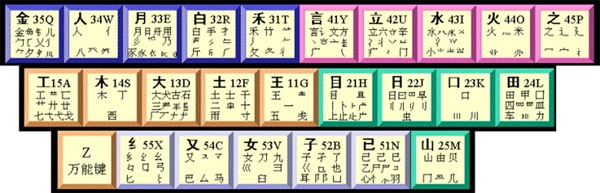

One of the most common methods for structural input is Kub Qixing (Wubing zixing - “input in five lines”). How does it work? Immediately I warn you: difficult.

In fact, all Chinese characters are divided into four groups:

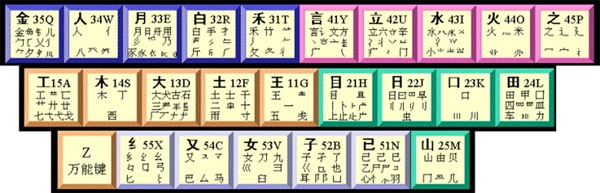

Well, we mentally broke the hieroglyph that we are going to enter into graphemes. What's next? First, let's look at the kill layout:

At first glance it may seem that the graphemes are arranged randomly. In fact, it is not. The keyboard is divided into five zones, according to the number of basic features, (in the figure they are marked with different colors). Inside each zone, the keys are numbered - from the center of the keyboard to the edges. The number is composed of two numbers from 1 to 5, depending on what basic features the grapheme is made of.

Well, let's start with the easiest to enter graphemes - the head graphemes of each key (they are highlighted in large font in the table). Each of them represents one of the 25 frequently used hieroglyphs, which were discussed above. To enter such a hieroglyph, just press the corresponding key four times. It turns out that 金 = QQQQ, 立 = YYYY, etc.

Thus, 毅 = U + E + M + C. To enter hieroglyphs consisting of more than four graphemes, you need to enter the first three graphemes and the last.

The most difficult to enter the hieroglyphs, consisting of two or three graphemes. Since there are so many of them, inevitably there will appear several hieroglyphs claiming the same key combination. To distinguish them, the developers came up with a special code. This code consists of two digits, the first is the ordinal number of the last feature of the hieroglyph, and the second is the number of the hieroglyph group (remember the four groups into which the hieroglyphs are divided).

Fortunately, when recruiting most of the frequently used hieroglyphs, you will not have to think about codes, because hieroglyphs will appear on the screen after the first two or three clicks. And the 24 most common characters can be entered at all with one click (they are assigned to the key).

The disadvantages of structural input are obvious: it is complex - only the digest version of its description was higher! To master it, the Chinese even invented a special mnemonic poem. But the structural method opens up the possibility of blind input, which increases the maximum speed of dialing up to 160 characters per minute. Therefore, professional compositors use it. And do not forget: 160 characters per minute - that's about 500 keystrokes for the same minute!

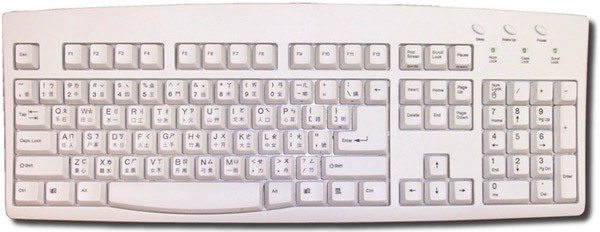

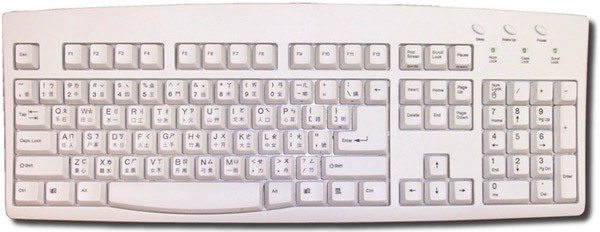

For structured input, the most common QWERTY keyboard is most often used, because the location of the hieroglyphs on it still has to be learned. But sometimes you can come across such keyboards with graphemes on the keys:

True, I have not seen such keyboards for all my time in China :)

Typewriters that use these typing methods simply do not exist - phonetic methods owe their appearance exclusively to computers. After all, using the phonetic method, you enter not the hieroglyph itself, but its pronunciation - and the system already finds the desired hieroglyph. But here's the problem: there are so many signs in Chinese that dozens of hieroglyphs can correspond to the same pronunciation. The necessary hieroglyph, as a rule, has to be selected manually from the list, which makes the input process rather slow. Predictive systems like T9 come to the rescue.

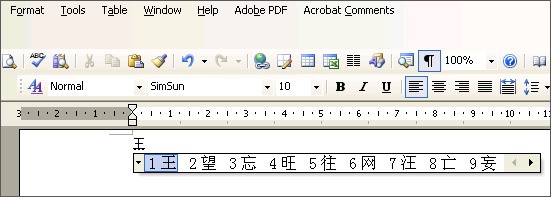

The most common phonetic method is the famous Pinyin . On its basis, a phonetic input system was built, which is included in the standard Asian Language Pack of the Windows system (starting with the XP version - before that it had to be installed additionally). Let's see how it works.

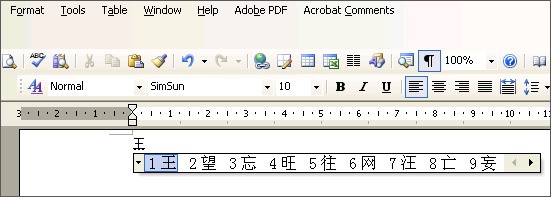

For example, we want to enter the word "blogger" - Wanmin .

We first collect wang (or wang3 indicating the tone to reduce the number of variants). After pressing the space, a character is inserted with a reading van . But this is not the van that we need. Click on it with the right button:

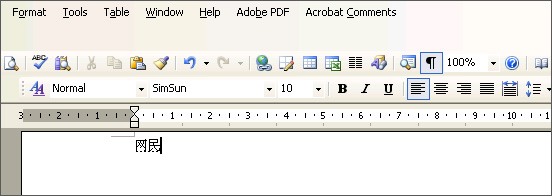

A long line of matches comes out. Breaking our eyes, we can look for our van there or just enter the second syllable of the word - min. The system is smart - it will find the word Wanmin itself in the dictionary and automatically select the right van and the right min . Banzai, we did it!

Google's Pinyin and Sogou Pinyin's input systems went further — they remember user preferences and suggest the right words based on the context.

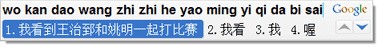

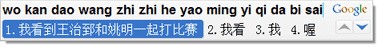

Here is an example of how Google Pinyin analyzes a seemingly furious sequence.

and gives the correct set option:

I saw Wang Zhizhi playing in the same match with Yao Ming (we are talking about two Chinese NBA basketball players). Particularly pleased that the names are spelled correctly.

In Taiwan, there is also an alternative to the pinyin system - input by Zhuyin (Zhuyin). It is not the Latin alphabet that is used, but the syllabary alphabet with icons like hieroglyphs. Since the icons in the alphabet a bit, they are easy to scatter on the keyboard. In Hong Kong, there is a version of Romanization for the local dialect - Yutphin (Jyutping), it is also actively used for phonetic input.

The main disadvantage of phonetic input systems is the rather slow typing speed - about 50 characters per minute (compare with kilzysin with its 160 characters per minute). The fact is that the input of the hieroglyph by the pinyin method occurs, on average, for six keystrokes, whereas when inputting for kill qyxing , four will suffice. In addition, a blind set of this method is not possible. And then, you need to know pinyin / zhuyin , which is far from being suitable for every Chinese, because since the first grade of school, knowledge (if any) has had time to be a little bit sublime. And it is not always easy to remember how some rare hieroglyph is read. Therefore, in China, Ubi Tszyxing is gaining more and more popularity. However, pinyin is still easier to learn than structural methods. But a foreigner is just such a system as a balm for the soul.

As we see, for phonetic input, we also do not need any special keyboard - just any keyboard with the Latin QWERTY layout. Well, for example, the one in front of you is quite suitable :)

These methods are a combination of phonetic and structural input methods. The simplest example is the Yinxing method ( Yinxing - “sound and form”). The hieroglyph is typed by entering a transcription and pointing to a graphic element. A limited set of graphic elements is spaced across the keyboard, so it is theoretically not difficult to remember them.

In practice, hybrid input systems are gradually dying out. They require from the user at the same time knowledge of complex combinatorics of structural systems and a good mastery of transcription. It's easier to master one thing perfectly.

And no. In China, the structural method of kill and phonetic pinyin are most popular. In Taiwan, Zhuyin's phonetic method is loved (because many people taught him at school, and not pinyin ) and the outdated structural method of the qanjie (Cangjie). It was invented back in 1976 and has since retained all its flaws: this method is very difficult to introduce punctuation marks, you must always guess the correct way to break the hieroglyph and remember the complex layout (many Taiwanese even stick it on the monitor). In Hong Kong, qiangjie is taught in school and clearly prefers it to all other methods.

It turns out that none of the listed methods of keyboard input is ideal. It is not surprising that the Chinese decided to cling to their last hope - recognition. Now recognition of both speech and handwriting is included in the standard Language pack Windows 7. It is assumed that before using it is better to transfer the system to the “learning mode” for at least 15 minutes to give it time to get used to your handwriting and speech features.

But the methods based on recognition, and not widespread. Keyboard input is still considered more reliable.

Recognition of oral Chinese is complicated by the fact that the proportion of people speaking with perfect pronunciation is not so large. Dialect features come out here and there and spoil the whole picture. Foreigners, for whom mastering four tones, is already a feat, and there is no need to speak.

Handwriting hieroglyphs seems to be simpler, and now there are many PDAs that support this input method. But this method has not reached wide application. The fact is that the Chinese, for the most part, write in incomprehensible italics and it can be difficult for them to rearrange themselves to the slow delineation of each feature. Often the problem is that they simply do not remember the normal order of the devil, because they are used to writing abbreviated forms! It turns out that input based on recognition is suitable mainly for language learners, which is actively used by online dictionaries. For example, on the site of the popular Nciku everyone is invited to draw the desired character with the mouse, and then choose from the options offered by the system:

Experimental Chinese keyboard, senseless and merciless.

After all, that's how you imagined it

Yes, yes, Chinese keyboards with thousands of keys exist. True for obvious reasons, they do not go into mass production, while remaining a kind of artifact.

But, you see, it’s still nice to realize that there is such a keyboard somewhere!

Happy programmer!

Julia Dreyzis,

team leader lexicographical descriptions of Chinese

PS Other my articles on Chinese language and Chinese culture can be found on the Lingvo team blog .

(The article used pictures from wikipedia.org and magazeta.com)

Update: Julia Dreyzis is now on Habré - dalimon , please love and favor.

Background: typewriters

For several thousand years, the clever Chinese managed to bring the number of hieroglyphs to 50,000 with a tail. And although the number of characters needed in everyday life is not measured in tens of thousands, it doesn’t matter what you might say, the standard set of the old typography is 9000 letters.

For a long time, the set was carried out according to the principle “for each hieroglyph is a separate printed element”. Therefore, I had to work with monster typewriters like this:

')

Typewriter firm "Shuanghe", 1947 (the principle of operation was invented by the Japanese Kyoto Sugimoto in 1915).

Its main element is a bank of hieroglyphs on an ink pad. Above the hieroglyphs there is a mechanical system: a handle, a “foot” for gripping and a reel with a sheet of paper. The whole mechanism, along with the reel following the handle, is able to move left, right, forward and backward due to the effort of the driver. To type the text, the driver searches for a long time with a magnifying glass for the desired hieroglyph, places the system above it and presses the "foot" on the handle, which grabs the hieroglyph on the fly, unwraps it, stamps it on a piece of paper. At the same time, the sheet reel rotates slightly, providing space for the next character. Of course, the process of printing on such a unit is extremely slow - an experienced operator could recruit no more than 11 characters per minute.

In 1946, the famous Chinese philologist Lin Yutan proposed a version of a typewriter built on a completely new principle - the decomposition of hieroglyphs into its component parts.

Lin Yutang Electromechanical Typewriter, 1946

In contrast to the overall predecessors, the new machine was no more than its Latin counterparts, and the keys on it were few. The fact is that the keys corresponded not to hieroglyphs, but to their component parts. In the center of the device was a "magic eye": when the driver pressed the key combination, a version of the hieroglyph appeared in the "eye". To confirm the choice, it was necessary to press an additional function key. With only 64 keys, such a machine could easily provide a set of 90,000 characters and a speed of 50 characters per minute!

Although Lin Yutang managed to get a patent for his invention in the United States, it never went to the masses. It is not surprising, because the production of one such device at that time cost about 120,000 dollars. Moreover, on the day when the presentation was appointed for the Remington company, the machine refused to work - even the magic eye did not help. The idea was successfully postponed until better times.

But in the era of the wide spread of computers, Lin Yutang's idea of decomposing hieroglyphs into its component parts gained a new life. It formed the basis of the structural input methods for Chinese characters, which we will now discuss.

(By the way, in the 1980s, the Taiwanese company MiTAC even developed, directly on the basis of Lin Yutang’s coding system, its own structural input method, Simplex.)

Structural methods

At least a dozen of such methods are known, and all of them are based on the graphic structure of a hieroglyph. Chinese characters are puzzles assembled from the same parts (the so-called grapheme). The number of these graphemes is not so large - 208, and they can already be “stuffed” into a regular keyboard. True, we get about 8 graphemes per key, but this problem is easily solved.

One of the most common methods for structural input is Kub Qixing (Wubing zixing - “input in five lines”). How does it work? Immediately I warn you: difficult.

In fact, all Chinese characters are divided into four groups:

- The basic 5 traits (一, 丨, 丿,,) and another 25 very frequently used hieroglyphs (each of them is associated with a key).

- Hieroglyphs, between the graphemes of which there is a certain distance. For example, the hieroglyph consists of graphemes 艹 and 田, between which there is a distance (although in printing they are slightly “pressed” and it may seem to you that there is no distance between them).

- Hieroglyphs whose graphemes are connected to each other. Thus, the hieroglyph is a grapheme 月 connected to a horizontal line; Consists of a grapheme 尸 and a folding line.

- Hieroglyphs whose graphemes intersect or overlap. For example, the character is the intersection of the graphemes 木 and 一.

Well, we mentally broke the hieroglyph that we are going to enter into graphemes. What's next? First, let's look at the kill layout:

At first glance it may seem that the graphemes are arranged randomly. In fact, it is not. The keyboard is divided into five zones, according to the number of basic features, (in the figure they are marked with different colors). Inside each zone, the keys are numbered - from the center of the keyboard to the edges. The number is composed of two numbers from 1 to 5, depending on what basic features the grapheme is made of.

Well, let's start with the easiest to enter graphemes - the head graphemes of each key (they are highlighted in large font in the table). Each of them represents one of the 25 frequently used hieroglyphs, which were discussed above. To enter such a hieroglyph, just press the corresponding key four times. It turns out that 金 = QQQQ, 立 = YYYY, etc.

Thus, 毅 = U + E + M + C. To enter hieroglyphs consisting of more than four graphemes, you need to enter the first three graphemes and the last.

The most difficult to enter the hieroglyphs, consisting of two or three graphemes. Since there are so many of them, inevitably there will appear several hieroglyphs claiming the same key combination. To distinguish them, the developers came up with a special code. This code consists of two digits, the first is the ordinal number of the last feature of the hieroglyph, and the second is the number of the hieroglyph group (remember the four groups into which the hieroglyphs are divided).

Fortunately, when recruiting most of the frequently used hieroglyphs, you will not have to think about codes, because hieroglyphs will appear on the screen after the first two or three clicks. And the 24 most common characters can be entered at all with one click (they are assigned to the key).

The disadvantages of structural input are obvious: it is complex - only the digest version of its description was higher! To master it, the Chinese even invented a special mnemonic poem. But the structural method opens up the possibility of blind input, which increases the maximum speed of dialing up to 160 characters per minute. Therefore, professional compositors use it. And do not forget: 160 characters per minute - that's about 500 keystrokes for the same minute!

For structured input, the most common QWERTY keyboard is most often used, because the location of the hieroglyphs on it still has to be learned. But sometimes you can come across such keyboards with graphemes on the keys:

True, I have not seen such keyboards for all my time in China :)

Phonetic methods

Typewriters that use these typing methods simply do not exist - phonetic methods owe their appearance exclusively to computers. After all, using the phonetic method, you enter not the hieroglyph itself, but its pronunciation - and the system already finds the desired hieroglyph. But here's the problem: there are so many signs in Chinese that dozens of hieroglyphs can correspond to the same pronunciation. The necessary hieroglyph, as a rule, has to be selected manually from the list, which makes the input process rather slow. Predictive systems like T9 come to the rescue.

The most common phonetic method is the famous Pinyin . On its basis, a phonetic input system was built, which is included in the standard Asian Language Pack of the Windows system (starting with the XP version - before that it had to be installed additionally). Let's see how it works.

For example, we want to enter the word "blogger" - Wanmin .

We first collect wang (or wang3 indicating the tone to reduce the number of variants). After pressing the space, a character is inserted with a reading van . But this is not the van that we need. Click on it with the right button:

A long line of matches comes out. Breaking our eyes, we can look for our van there or just enter the second syllable of the word - min. The system is smart - it will find the word Wanmin itself in the dictionary and automatically select the right van and the right min . Banzai, we did it!

Google's Pinyin and Sogou Pinyin's input systems went further — they remember user preferences and suggest the right words based on the context.

Here is an example of how Google Pinyin analyzes a seemingly furious sequence.

and gives the correct set option:

I saw Wang Zhizhi playing in the same match with Yao Ming (we are talking about two Chinese NBA basketball players). Particularly pleased that the names are spelled correctly.

In Taiwan, there is also an alternative to the pinyin system - input by Zhuyin (Zhuyin). It is not the Latin alphabet that is used, but the syllabary alphabet with icons like hieroglyphs. Since the icons in the alphabet a bit, they are easy to scatter on the keyboard. In Hong Kong, there is a version of Romanization for the local dialect - Yutphin (Jyutping), it is also actively used for phonetic input.

The main disadvantage of phonetic input systems is the rather slow typing speed - about 50 characters per minute (compare with kilzysin with its 160 characters per minute). The fact is that the input of the hieroglyph by the pinyin method occurs, on average, for six keystrokes, whereas when inputting for kill qyxing , four will suffice. In addition, a blind set of this method is not possible. And then, you need to know pinyin / zhuyin , which is far from being suitable for every Chinese, because since the first grade of school, knowledge (if any) has had time to be a little bit sublime. And it is not always easy to remember how some rare hieroglyph is read. Therefore, in China, Ubi Tszyxing is gaining more and more popularity. However, pinyin is still easier to learn than structural methods. But a foreigner is just such a system as a balm for the soul.

As we see, for phonetic input, we also do not need any special keyboard - just any keyboard with the Latin QWERTY layout. Well, for example, the one in front of you is quite suitable :)

Hybrid methods

These methods are a combination of phonetic and structural input methods. The simplest example is the Yinxing method ( Yinxing - “sound and form”). The hieroglyph is typed by entering a transcription and pointing to a graphic element. A limited set of graphic elements is spaced across the keyboard, so it is theoretically not difficult to remember them.

In practice, hybrid input systems are gradually dying out. They require from the user at the same time knowledge of complex combinatorics of structural systems and a good mastery of transcription. It's easier to master one thing perfectly.

So is there a “standard” method?

And no. In China, the structural method of kill and phonetic pinyin are most popular. In Taiwan, Zhuyin's phonetic method is loved (because many people taught him at school, and not pinyin ) and the outdated structural method of the qanjie (Cangjie). It was invented back in 1976 and has since retained all its flaws: this method is very difficult to introduce punctuation marks, you must always guess the correct way to break the hieroglyph and remember the complex layout (many Taiwanese even stick it on the monitor). In Hong Kong, qiangjie is taught in school and clearly prefers it to all other methods.

Recognition Based Methods

It turns out that none of the listed methods of keyboard input is ideal. It is not surprising that the Chinese decided to cling to their last hope - recognition. Now recognition of both speech and handwriting is included in the standard Language pack Windows 7. It is assumed that before using it is better to transfer the system to the “learning mode” for at least 15 minutes to give it time to get used to your handwriting and speech features.

But the methods based on recognition, and not widespread. Keyboard input is still considered more reliable.

Recognition of oral Chinese is complicated by the fact that the proportion of people speaking with perfect pronunciation is not so large. Dialect features come out here and there and spoil the whole picture. Foreigners, for whom mastering four tones, is already a feat, and there is no need to speak.

Handwriting hieroglyphs seems to be simpler, and now there are many PDAs that support this input method. But this method has not reached wide application. The fact is that the Chinese, for the most part, write in incomprehensible italics and it can be difficult for them to rearrange themselves to the slow delineation of each feature. Often the problem is that they simply do not remember the normal order of the devil, because they are used to writing abbreviated forms! It turns out that input based on recognition is suitable mainly for language learners, which is actively used by online dictionaries. For example, on the site of the popular Nciku everyone is invited to draw the desired character with the mouse, and then choose from the options offered by the system:

And yet it exists!

Experimental Chinese keyboard, senseless and merciless.

After all, that's how you imagined it

Yes, yes, Chinese keyboards with thousands of keys exist. True for obvious reasons, they do not go into mass production, while remaining a kind of artifact.

But, you see, it’s still nice to realize that there is such a keyboard somewhere!

Happy programmer!

Julia Dreyzis,

team leader lexicographical descriptions of Chinese

PS Other my articles on Chinese language and Chinese culture can be found on the Lingvo team blog .

(The article used pictures from wikipedia.org and magazeta.com)

Update: Julia Dreyzis is now on Habré - dalimon , please love and favor.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/104083/

All Articles